fear

The Korubos are scared

17.dez.2017

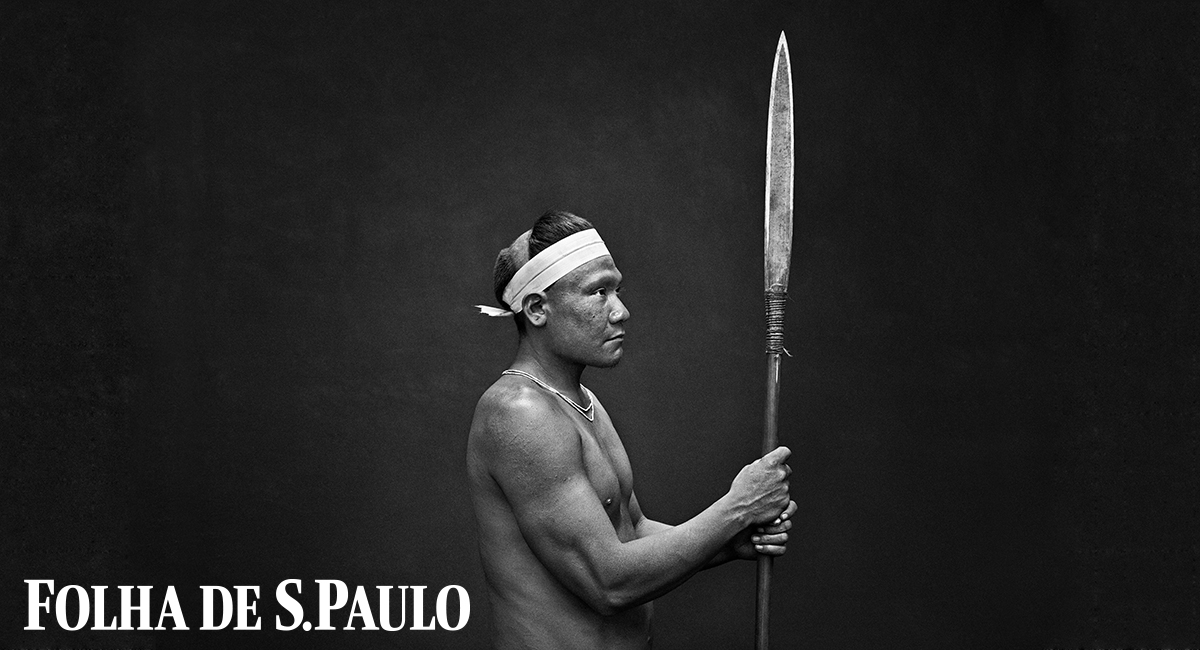

Brazil's most prominent and internationally acclaimed photographer has transformed the Earth's biggest forest into a studio in order to produce what could be his last major project: "Amazonia". In this project, he turns his attention to the indigenous peoples - such as the Korubos- who have had very little contact with "white culture".

Folha reporters were invited by both the photographer and the tribe to tag along for part of the expedition and visit their land in the west of Amazonas state. This was the first time that a team of documentarians was welcomed into the villages of the Korubos, a tribe that is considered violent and whose members are referred to as "clubbers" - a reference to the clubs they bear, as opposed to bows and arrows.

The Korubos (whose safety has been threatened by the illegal exploitation of the land's natural resources) are in distress and scared for their future and the future of their people – and want to speak up.

The Korubos Are Speaking Up

In the more remote corners of the forest, where they have always lived, the korubos- who are also referred to as "violent clubbers Indians" - run toward the adventurer they spotted, clenching their clubs in their fists. They team up on the adventurer and start yelling in an intense fashion, all while staring directly into his eyes. The white adventurer, who is scared at first, is then overcome by a sensation of perplexity due to the guttural sounds they endlessly emit:"Hey, hey, hey, hey, hey...".

That's how the Korubos greeted Sebastião Salgado, the world's most famous photographer who visited their village in the Vale do Javari for 20 days during the months of September and October, in order to work on his latest project, "Amazonia".

The Korubos are a tribe consisting of approximately 80 members who - with the exception of the dealings carried out on a regular basis with government officials and the occasional exchange with a handful of other people who live in the forest - rarely interact with social groups at all, whether indigenous or otherwise. The group that was contacted is divided between two villages along the banks of the Ituí river, in the Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory, in Western Amazonas, along the Brazil-Peru border: 3,500 kilometers away from São Paulo and 1,200 kilometers away from Manaus.

{{imagem=3}}

The group, which has been classified as "recently contacted" - in other words it has had very few interactions with non-indigenous peoples - abides by traditional norms. Few members speak Portuguese and they easily succumb to diseases common among the non-indigenous. In light of this, they try to avoid bringing whites into their community.

Salgado's expedition was a landmark in the sense that it was the first time that journalists and documentarians were taken in by the Korubos. Folha reporters were invited to visit by both Salgado and the tribe.

In the 20th century, the tribe earned a reputation for violently attacking those who intruded upon their territories with clubs - their use of the weapon is what earned them their nickname. Non-indigenous invaders would then retaliate, and this led to several massacres.

{{imagem=1}}

Sydney Possuelo, a specialist in indigenous affairs, organized an expedition to visit the Korubos in 1996, in order to bring this vindictive attacks to an end. The initiative lasted months, having made contact with 21 members of the community. Two separate groups visited the tribe in 2014 and 2015.

The region was recently considered to have been the stage of attacks against lone tribe members. An expedition conducted by Funai - or the "National Indian Foundation", a Brazilian governmental agency that helps protect indigenous interests - encountered illegal miners who were active in the region, but found no evidence of bloodshed. The Indians fear that lone tribe members could be targeted in future attacks, and so they have decided to speak up.

{{imagem=2}}

THE PATH

Along the banks of the Ituí river are the two Korubo villages, situated at the halfway point between the Solimões River and the Amazonas-Acre state border. The region's 8.5 million hectares make it the second biggest Indian reservation, only falling behind Terra Ianomâmi, which extends through Roraima and the north of Amazonas. It is the home of at least seven ethnic groups and it also houses the biggest number of uncontacted groups (estimated at around 14).

When looking slightly to the north on a map, one will come across the exact point where the Amazon river flows into Brazil from Peru. The Solimões river begins on the Brazilian side and its starting point is precisely where the triple frontier between Peru, Colombia and Brazil is located.

At the crossing are the towns of Leticia, the capital of the Colombian state of Amazonas, and Brazilian town Tabatinga. The two towns are separated by a stretch of asphalt and scattered traffic cones and not much else. On the Peruvian side, separated from the two other towns, is the small town of Santa Rosa de Yavari, located on an island in the middle of the vast river.

Tabatinga is the biggest Brazilian city in the region, where personnel belonging to federal institutions such as the military, Federal Police, Public Prosecutor's Office and Funai, among others, are stationed. The trip from the town to the land of the korubos is done by boat, heading south and zigzagging through the Javari River, which leads to the Itaquaí River, by the city of Benjamin Constant. After the Itaquaí River comes Ituí. That's where the Funai branch that supports remote tribes - the Ethno-environmental Protection Front - is located.

{{imagem=4}}

{{imagem=5}}

The base is strategically located at the intersection of the two rivers - which marks the northernmost frontier of the Indian reservation - enabling agents to monitor the river and keep transgressors out.

After an 11-hour journey on a bass boat from Tabatinga to the Korubo community, the crew arrived at the hunting camp where it met with Sebastião Salgado, who was already with the group.

The second the crew made it to the clearing, where the tents ("tapiris") were set up, they began a ritual in which they danced and greeted the adventurers. They gathered in a circle, holding hands and raising their clubs with the left hand.

AN INEBRIATING DANCE

The alien is now the center of attention. People look straight into his eyes making percussive, guttural sounds in a repetitive and inebriating form over a very long period of time: "Hey, hey, hey...", they chant, stomping the soles of their feet on the ground in rhythm for 30 or maybe 40 minutes that seemed more like an eternity due to the altered state of mind that the ritual provoked.

Meanwhile, as the circle emits its monosyllabic chant, one person narrates a story, followed by another, and so on. Even a fluent speaker of the language of the korubo could not have made out the stories that were being narrated amid all the chanting.

A specialist in indigenous affairs said jokingly that, in the past, this very ritual had been used to surround potential enemies. They were all armed with clubs. If all hell broke loose, not a shred of evidence would have remained.

But in the end the repetitive chant is just a distraction, a sort of "trip". The ritual comes to an end and I am taken to my tent, which is where I set up my hammock. The second I settle down, the korubos call for me, so I return to the clearing where several of them are seated on logs as if they were couches. They all desperately want to speak.

{{imagem=24}}

Sebastião Salgado has been producing a series of photographic documentations of the Amazon, giving special attention to the indigenous groups that have had very little contact with "white" culture. It is an extension of his earlier work, "Genesis", which included pictures of the zo'és tribe, in the state of Pará, as well as other ethnic groups. He has sought to offer a portrait of the indigenous peoples of Brazil: inhabitants of the largest forest in the world whose very existence has been put on the line in the face of the unsustainable exploitation of its resources.

He has said that "Amazonia" may very well be his "final project" due to his desire to do something he considers of the utmost importance: go over old negatives and revisit and re-edit passed projects. And the process of going over thousands of frames, choosing from piles of previously discarded ones, and putting together the pages of upcoming books takes the kind of time that long trips simply won't allow for.

But perhaps the "real reason" for wanting to spend more time at home has to do with the birth of his first granddaughter, the soon-to-be daughter of moviemaker Juliano Salgado who co-directed "The Salt of the Earth" and has a son in college.

Salgado and his wife Lélia have moved to São Paulo temporarily in order to accompany the birth of their granddaughter and spend time with her during her first few weeks.

In order to create "Amazonia", Salgado has been visiting several groups other than the korubos and will go on other expeditions until 2019, which is when he intends on displaying the project and releasing a new publication.

{{imagem=25}}

{{info=1}}

GLOSSARY

Korubos Indians whose language is derived from Pano. The term "Korubo", however, is not the same one that members of the tribe use to refer to themselves; rather, it is used by the Matis, and it means "covered in mud" ("koru" means "mud"). The term was attributed to them because they would use mud to cover their skin as a form of preventing mosquito bites.

Kulina an indigenous people that speaks Arawá. They refer to themselves as "madija" (pronounced "ma-di-HA") which means "people" in Arawá. The language varies considerably according to the gender of the speaker.

Marubos Indigenous peoples whose language belongs to the Pano family (including the languages of the Matis, Matsés and Korubos). It is believed that these groups survived attacks carried out by rubber tappers in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Matis an indigenous people whose language is derived from Pano.

Indigenous names Indigenous peoples do not attribute last names to individuals. In the case of the Korubos, "Leium", "Pëxkn" and "Mayá" are examples of common first names. For the sake of Brazil's registration laws, the name of an individual's ethnicity is added to their first name. Officially, members of the Korubo group would be registered as "Leium Korubo", "Pëxkn Korubo" or "Mayá Korubo", for example.

Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory Established in 2001, the territory is the second biggest reservation in the country, spanning across 85 thousand km2 of land, and home to the largest number of uncontacted groups.

Tracajá A kind of turtle (Podocnemis unifilis) typically found in South America, especially in the Amazon river basin.

{{imagem=11}}

"Does Anyone Here Know How to Kill an Animal Using a Blowpipe?"

"Does anyone here know how to kill an animal using a pipe? Has anyone boiled a monkey in water?"

Those were the first phrases that the Indian Malevó recalls listening in on after the traditional greeting "E-hê" which the korubos shout out in order to let others know that they are arriving.

The year was 1996 when the Funai team led by Sydney Possuelo, finally got within earshot of the Korubo village, following a months-long process of nearing in on the community that had been entirely isolated up until then. Referred to as "clubbers", the Korubo people had been known for violently attacking intruders and disfiguring victims with their clubs.

The language that the interpreter was speaking was similar to Malevó's, while the questions he was asking suggested an understanding of the customs of the korubo people. Malevó, who, at the time, was the youngest warrior in the group, was drawn to him.

{{mosaico=1}}

Malevó replied something along the lines of: "We are people just like you, we hunt just like you, we also cook our prey and eat monkey meat. We have similar customs". And just like that, contact had been made.

But now the korubos now found themselves in front of a journalist 21 years after that initial encounter took place, and in that interim Malevó had become one of the group's main leaders. He recalled that the interpreter who belonged to the matis group greeted them before saying that he was accompanied by white men who came bearing gifts.

The korubos, who have a history of being slaughtered by non-indigenous transgressors, nodded them in. That was the first time that outside ties had been established with the "clubbers", whose main leader at the time, despite their culture's patriarchal structure, was a woman named Mayá. That's why the group that was contacted for the first time in 1996 is also referred to as the "Group of Mayá".

There were few of them, and they had been left in shambles following an attack carried out by white intruders one year prior.

{{imagem=7}}

Seated next to a campfire that had been set up to roast fish, Pëxkn, 65, stood out because of his notably wide smile. He would walk around naked since he had always lived in the forest in isolation until he was forced to flee from whites and other tribes two years ago. He belonged to the "Coari Group" (a reference to the river where the paths of the whites crossed with his own and that of other Indians), or the "2015 Group", a group with peculiar customs, such as the refusal to wear "white" clothes - members of other groups that have already been contacted often wear shorts and t-shirts, for example.

The way they communicate is also different: they express themselves in a purer fashion when compared to the korubos who have incorporated elements of the language spoken by their neighbors, the mati tribe, and even non-indigenous elements, into their own language.

Pëxkn's group made contact with whites after being massacred by Indians belonging to a different ethnic group. They had lived in isolation up until then. Members of the mati tribe, who had managed to communicate with korubos before, thought that, in the event that they encountered one another, they would be able to explain to the isolated group that they were planning on farming nearby.

But that's not what happened. The korubos went over to the matis, two of whom were bludgeoned to death. The community, which had barely had any contact with non-indigenous peoples, believed it was expelling whites.

{{imagem=8}}

The matis, who use firearms to hunt, decided to retaliate by showing up on the scene and killing 9 of the 30 members of the group. The use of shotguns strengthened the theory that they were being attacked by whites. Shaken to the core by so many deaths, the korubos fled and joined another indigenous community, which reached out to the Funai. And thus the "contact of 2015" was established.

Some among this particular group of korubos were overcome with anger since a different indigenous group used lead bullets to attack them - a fact they consider unfair.

Seated next to Pëxkn, and wearing shorts, was Tsamavó, a member of the "Group of Mayá". He asked me to run my hand along his shoulder. Beneath his scars were pebble-like objects. "It's lead", he explained. The bullet fragments are a reminder of the massacre that his group was subjected to before they reached out to the Funai.

In 1995, a group of whites settled on land by the korubos. Tsamavó's parents and others decided to steal bananas from their land. Shortly after leaving, they were ambushed. His parents were killed and several other Indians were injured.

The survivors fled without even burying those who had been killed. They managed to settle into a safe location - the same place Possuelo's crew managed to make contact with them in 1996.

Mayá, who, in the blink of an eye, had suddenly become the eldest member of the group, said that from that moment on they started to really fear non-indigenous peoples. But, as Malevó relayed, that changed when they started to put their trust in the specialist in indigenous affairs who came bearing gifts.

{{imagem=9}}

OCCUPATIONS ARE ON THE RISE

After recalling the conflicts that took place two decades ago, Txitxopi, a "Group of Mayá" warrior, says that they're afraid again: "Recently, we spotted fishermen not far from the village. The number of fishermen has gone up and they're taking away our fish and our turtles. They come whenever they please. If a fisherman shot my son, no one would see it, no one would find out about it".

The Indians were very alarmed by news of the possible massacre of two isolated groups in the Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory. No one knows which groups they may have belonged to: could they have been korubos who had remained in isolation in the forest?

Txitxopi, who is also a Funai collaborator, participated in a recent expedition to the Jutaí river region to determine whether or not gold miners had killed uncontacted Indians. "They may be killing our brothers in the jungle", he said, referring to the group of roughly 80 family members who they were separated from.

The expedition came across dozens of dredgers that had belonged to gold miners scattered along the banks of the river. "We saw 30 boats that were very close to where our uncontacted family lives. I'm afraid they'll attack our brothers", Txitxopi said.

Xikxu was also around when the group was first contacted in 1996. He expressed a feeling of betrayal with regard to the Funai due to the retraction of protection guarantees that, in some form or other, had been promised to the korubos: their "contract" with Mr. Possuelo would have involved kicking out intruders in exchange for their "pacifism".

"Before, when Possuelo would contact us, there were no fishermen around here. Now there are. There were no gold miners. Now there are. There are people who are hunting our prey, our jaguars, our monkeys. We need to come together if we want to kick out intruders. Currently, Funai is very frail. Nowadays, a single person runs the base. The Sesai [Special Indigenous Health Department] also needs to be improved. It has not managed to avoid illnesses, and whenever we call them, they take too long to arrive", Xikxu said.

His unease was also reflected in his grim take on the future: "If fishermen and hunters can come and eat everything, what will my grandchildren eat? What will my children eat? I went hunting near the village and I came across footprints that belonged to fishermen. They are intruding. They are too close to our land".

{{imagem=10}}

Urucum Seeds, Bracelets and Penil Wires

"The korubos are sober", said Bernardo Natividade da Silva, a specialist in indigenous affairs at Funai's Ethno-environmental Protection Agency. In material terms, their culture is considerably simpler than those of other ethnicities - a fact that becomes apparent upon analyzing their bodywear: they barely have any.

Men wear bracelets and penile wires; they cover their bodies entirely using urucum seeds, lending them an even, red complexion from head to toe.

{{imagem=12}}

They have two kinds of haircuts, both of which are peculiar. They resort to local leaves with blade-like edges to either shave off the back of their heads, or they shave off a straight patch of hair over the tops of their heads - as if they were wearing headbands - extending from one ear to the other (while the rest of their heads are covered in hair).

Women wear no clothes at all, with the exception of a bear necklace, and when they have infants they wear a strap made out of vegetable fiber so they can carry babies on their backs. They use the tips of their fingers to spread urucum on their bodies, forming different shapes and figures (in contrast to the men, who use urucum to cover their entire bodies).

And that's about it.

In his celebrated poem, "Mistake of the Portuguese" ("When the Portuguese arrived / In a heavy storm / He clothed the Indian"), Oswald de Andrade describes the arrival of navigator Pedro Alvares Cabral, supposing that the Indians were naked. The modernist writer was unaware of the fact that nudity is a subjective thing: it varies from one people to the next. While a woman in Afghanistan may feel naked when her cheeks are exposed, the korubo people feel naked when their glans are exposed. The wires help cover their foreskin, which conceals their "privates" (as Pero Vaz de Caminha, the knight who accompanied Pedro Alvares Cabral, wrote in his letter to the king of Portugal).

MILITARY SOBRIETY

The sobriety of the korubo people can also be encountered in their weaponry. For hunting, they use blowpipes to fire poisonous darts that are 30 centimeters long. Crafting the weapon requires a delicate touch, but the weapons themselves are unadorned. The same is true of their clubs (borduna), which are made from sturdy wood and look like extensions of the bodies of those bearing them.

{{imagem=13}}

{{mosaico=2}}

Their spears have sharp wooden tips and embody simplicity. They can be used to attack bigger animals, such as the tapir that was hunted down in the expedition that Sebastião Salgado took part in. The mammal was so big that it had to be cut into parts so that it could be brought back to the campsite.

The arsenal of the korubo people makes them stand apart from other Indians. After being contacted, younger generations started learning how to use a bow and arrow, which some of them can even craft and use. However, among an entire group of approximately 80 Indians, none of them wielded bows.

MALARIA, SCORPIONS AND SNAKES

The main plague faced by the korubos is malaria. Mosquitoes along the river banks carry the disease. The group used to live in high altitudes, far away from the watercourses. But currently they are vulnerable. Cases have been on the rise and the medical departments have not yet managed to implement preventive treatment policies. Victims are treated, but then they get sick again. Some cases are unbelievable, like Seatvó's, for instance: the 12-year-old has already contracted the disease 25 times.

{{imagem=16}}

During the 10 days the report was being elaborated on the korubo campsite, a Sesai team ("Sesai" stands for "Special Indigenous Health Department", an overcrowded service at the Funai base, which is a three-hour boat ride away) was summoned on three occasions.

Several patients were diagnosed with malaria, and on their third trip to the campsite, a mother accompanied her sick child back to the base for treatment. Beto Marubo, a former Funai employee, said that "uncontacted Indians simply get sick and die".

Another case that illustrates the fragility many Indians are subject to was that of a group contacted back in 2014. "The elders had died from Malaria", said Bernardo Natividade, one of very few white people who can speak Korubo: "They fled from their farms back in 2013, almost as if to flee from the disease itself".

COLLECTIVE WAILING

Korubos can be quite scandalous when someone gets ill, or an accident happens, leading to widespread wailing and desperate yelling that brings the village's serenity to an end.

One particular evening, a mother started screaming: her son had fallen into the water while playing on one of the Funai boats that had laid anchor by one of the river banks, and he almost drowned. Her screams were a form of alarming the others. When everyone made it over to the river, the boy wasn't surprised, he was startled.

There was more collective yelling the next day after a man got bitten by a scorpion. The day after that, a child that was swimming was bitten by a snake. The parents had seen the snake. It was green: a good sign according to popular belief, because it meant it wasn't poisonous like the much-feared Jararaca snake.

Mr. Natividade patched the boy up and used Mr. Salgado's satellite phone to notify agents at the medical base. The following day, the boy was running around with his friends, proud of his bandage.

{{imagem=27}}

After spending several days at the hunting campsite, everyone went back to their homes, and the photographer and his team moved on to their next spot, close to one of the korubo villages. After setting up the tents, Bebé, the bushman, cut the grass enveloping it.

We took an open path that we got on just beyond our tent, and it took us through the jungle. I followed Salgado. He said that, by tidying everything up, the bushman will keep us from stepping on any snakes". As soon as he said that, a small serpent slithered past the space between us. "Like that one", I said. Salgado did not follow. "Like that snake over there", I repeated. And just then, Xikxu the Indian mercilessly struck the small Jararaca snake.

FAREWELL, KORUBOS

The last day of our expedition began early, when Xikxu repeatedly started yelling the made-up word "Jornalisti". He had this smirk on his face, suggesting he had something up his sleeve. But as soon as I got close to him, Xikxu got serious, and his semblance indicated he was about to give a speech: "You will go back home and write, and tell our stories to the Brazilians who live in the city. Then, the president of Brazil will read what you wrote, and Salgado's pictures will support it. Then you will have to tell the president that more people are needed at the Funai base. Currently, there is only one person, and that person can't accomplish everything that needs to be done".

{{imagem=28}}

"One more thing: when Possuelo worked here, he would come here all the time. You have to write to the president and then you need to come back to see if things have improved."

He finally said: "They need to hire Bebé, more people like Bebé!", referring to the assistant that Mr. Salgado had hired, a man with several years of experience when it came to surviving in the jungle.

In his apparent simplicity, Xikxu summarized the message that the group had wanted to send to the Brazilian government: the korubos need the government to do its job, and, in order for that to happen, leaders need to be present and employees need to know how to accomplish the most important tasks at hand. The message could not have been more clear-cut.

{{imagem=19}}

"They Are Desperate"

Sydney Possuelo, 77, who was in charge of the Funai when the korubos were first contacted, said that the "Indians are desperate" and he fears that conflicts and massacres will resurface if the government fails to supply the Funai with the necessary conditions to monitor the Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory and keep intruders out.

Possuelo, the now-retired specialist in indigenous affairs who was the president of Funai from 1991 to 1993, was responsible for the change in government initiatives directed at indigenous groups. Under his command, the foundation shifted in terms of its policies, protecting uncontacted groups - making sure they didn't have contact with other groups or whites - as well as groups that had recently been contacted - making sure they didn't have too much contact with society.

Thus, the Ethno-environmental Protection Fronts were conceived, such as the Vale do Javari, which takes care of the korubos, among others, and contains the main Funai base in the region.

"Before, thousands of fishermen would swoop in and leave with fish by the tons, while timber merchants would steal somewhere between 15 thousand and 20 thousand mahogany logs a year", he said.

{{imagem=17}}

"But the base on its own isn't enough. You need structure, communication logistics and transportation in order to fend off threats. If you don't have communication, you don't know what's going on, and by the time you find out, it's too late. If you don't have transportation, it'll take 14 days to get to the more remote villages", said Mr. Possuelo.

According to the specialist, the budget cuts that have taken place over the past few years have taken away the Funai's ability to adequately monitor the region: "I've never seen budget cuts this big. The base hasn't been achieving anything. Everything is falling apart. There are no employees and there's no money", he stated.

Mr. Possuelo explained to Folha from his home in Brasília that, as a result, there has been a rise in terms of trespassing, which, in turn, leads to more contact between intruders and Indians, which, in turn, gives rise to conflicts.

When it came to the alleged massacres of uncontacted Indians in the region, which were reported back in September, Mr. Possuelo blamed Funai for proceeding sluggishly: "They were negligent because they should have begun an investigation immediately. If massacres of the sort did in fact take place, then they had to have conducted an expedition. If it were a farm that belonged to white people, they would've done it immediately. But since they're Indians, they didn't".

He said he fears the korubo people may go back to violently dealing with intruders. "The Indians are desperate. They fight, they call out for help, but they don't get the attention they deserve. They may end up reacting violently, which would be a bad thing."

The former Funai coordinator in Tabatinga, Bruno Pereira, who currently works at the Vale do Javari Protection Front, helped organize a trip to one of the locations where massacres may have taken place.

{{imagem=18}}

The expedition to the Jandiatuba River began on November 10th and returned to Tabatinga on December 3rd. There were no signs that uncontacted Indians had been attacked, although both the Funai and the army encountered unlicensed gold miners in the region, a fact that had been reported by Folha on December 5th.

TICKING TIME BOMB

Mr. Pereira said the region was like a "ticking time bomb". Cuts in terms of public services opened the floodgates for non-indigenous intrusions that could lead to potentially violent conflicts. The September allegations referred to potential bloodshed that may have taken place in areas where bases were shut down due to a lack of funding.

"The weakening of bases leads to a decrease in Funai presence, and this is what you get: timber merchants coming in, gold miners who have already entered, drug-trafficking routes that pass through indigenous land The vale do Javari is either the first or second busiest route in terms of cocaine trafficking. The river is like an avenue. Recently, 800 kilograms of cocaine were seized", he said.

The rise in intrusions has left Indians scared: "The korubos hadn't even seen gold miners before: now, they see fishermen and hunters who they either attack, or get attacked by. There are korubo leaders who were around to see the Funai arrive 20 years ago, but currently, what they see is an institute in retreat".

{{imagem=21}}

Mr. Pereira believes that, on top of the budget cuts that were made as a result of the recession, the lack of employees can also be attributed to fact that the Funai's hiring processes for forest work are entirely inadequate. "The processes don't include job descriptions. It seems as if they were hiring employees for an office job in Brasília. People only find out they will be working in the jungle by the time they get the job. The candidates who join Funai are not specialists in indigenous affairs. A majority of the candidates who passed in the latest recruitment process in 2010 left due to this kind of incompatibility."

The case of Vitor Roger David is an example of said incompatibilities. He was selected back in 2010, when he worked in the finance department of a company in Rio de Janeiro. "I was shocked when I passed and discovered what the job specifically consisted of". He became one of the coordinators of an Ethno-Environmental Protection Front, where he was interviewed by Folha. The front is committed to protecting Indians within the reservation that are either isolated or that have been contacted recently.

"The application form did not explain what the mission was. It mentioned a 40-hour work week. In reality, working on a reservation consists of 60 days of non-stop work followed by a-30 day break. Plus, the job requires skills and knowledge concerning how to handle the forest or deal with Indians that were simply not mentioned. Also, they don't make you go through a training program once you get the job. Anyway, I left Rio de Janeiro and wound up here, working with isolated tribes. Obviously, I considered leaving, but then the challenge started to appeal to me, so I decided to stay."

{{imagem=20}}

According to Mr. David, the lack of qualified personnel has compromised his base's ability to monitor the area:

"Before, we were meticulous in our activities. But now, you would have to be one unlucky fisherman to get caught. We recently got lucky and confiscated a boat containing 230 turtles. The turtles are sold in Atalaia do Norte. Each one goes for around R$ 100 or R$ 150 [roughly US$ 30 to US$ 40]. The fisherman was carrying more than R$ 30,000 [around US$ 9,000 ] worth of turtles. Since, on the police report, they only get written up for entering federal property - in other words, no sanctions - it becomes a risk worth taking", he said.

FUNAI'S RESPONSE

The president of the Funai, Franklinberg Ribeiro de Freitas, said that the Jandiatuba River Protection Front is already being reactivated. "Other bases will be reactivated as more funding starts to come in".

When it came to delays surrounding the investigations into the possible massacres, he stated that "the issue isn't negligence, it has to do with the physiography of the region, which affects logistics significantly".

As far as hiring skilled employees goes, Mr. Freitas said the following:

"In an application process, given the extensive range of areas at Funai, it's hard to determine whether all candidates selected have the necessary expertise for the position in question. However, it is very important that the application forms provide more specific details concerning the available positions".

{{imagem=22}}

An Art Studio in the Middle of the Jungle

In his latest trip to the Amazon, Sebastião Salgado spent 60 days in the forest, 20 of which were spent with the Korubo group. The rhythm of his work is similar to the work of scientists, like anthropologists and linguists. He spends more time with his subjects than journalists typically do. When I asked him about his "decisive moment", an expression made famous by Henri Cartier-Bresson, the founder of Magnum photos, he replied by saying that his method was completely different from that which he considered his French friend's method to be.

Salgado, who graduated in economics, summoned a bell curve to convey his process: "I spend a long period of time immersing myself in a local community that I capture, and the quality of the pictures goes up as our chemistry evolves; then there comes a time where things become unproductive, forming a downward curve. My work consists of that entire process. There is no '"decisive moment'".

On his field trips, Salgado always takes a support team with him: one that he has planned to a T. Almost invariably among his helpers is renowned tour guide Jacques Barthelemy, who has accompanied the photographer ever since the "Genesis" project began 12 years ago, and who has missed out on very few trips ever since. A specialist on the groups being visited - who also handles the translating - and a bushman of sorts are also included on his team. Occasionally, others beyond this inner circle are proven necessary.

Since the korubos speak a language that still hasn't been mastered outside the community, Salgado took Beto Marubo, 41, an Indian who was born in the region who not only spoke marubo, his native language, but also matis, a language that the Korubos have mastered and that is similar to their own.

The specialist in indigenous affairs, Bernardo Natividade Silva, also accompanied Salgado as a Funai representative. He is one of very few white people who can understand the rudiments of Korubo, and helped translate conversations, especially whenever Beto Marubo's matis couldn't get the job done.

Also on Salgado's team was Carlos Travassos, a specialist in indigenous affairs and former-director of the Funai's Coordination for Isolated Indians. Currently, Mr. Travassos works for an NGO that is present in the awa-guajás area, in the state of Maranhão. Last but not least was Francisco da Silva Lima, the bushman who grew up in the region. He served in the army for eight years and had also been trained to survive in the jungle. "Bebé", as he was called, was responsible for setting up and maintaining the campsite, among other tasks.

HIGH TECH EQUIPMENT

On Salgado's checklist of items are: products that can purify even highly contaminated waters, a satellite phone that can establish a connection with any other phone in the world - even in highly remote places - and a portable studio, which includes a portable 60m2 canvas sheet, strategically set up for making infinity coves.

In a world where electronic devices prevail and batteries need recharging, Salgado also brought two rollable solar panels with him, managing to keep his photography equipment (four cameras), phone, computers and other items charged on any given day.

{{imagem=29}}

Mr. Barthelemy brought a huge amount of medical supplies with him, such as antivenom for snake bites, suturing instruments, bandages and drugs for all sorts of illnesses, not to mention a huge variety of bug repellents in order to prevent mosquito bites, and anti-malaria medicine given how common the disease is in the Javari region.

As far as work procedures go, he is also responsible for archiving a copy of each photo Salgado takes, bagging the pictures on a daily basis in envelopes different from the ones the photographer uses. "Along with the originals I produce a backup. When Jacques returns to Paris, he goes with one set and I go with the other", Salgado explained. They travel in separate planes and they each carry an entire set of the pictures with them.

PROTECTION

Mr. Barthelemy is a renowned tour guide known for going to places that are difficult to access. The 71-year-old has a reputation for showing scientists around craters and volcanoes. His ability to foresee risks and come up with solutions is noteworthy. Toward the end of the trip, Salgado said: "Did you notice how during a trip that practically lasted two months, in which we ate just about anything and drank river water, no one got sick?". Surely, Mr. Barthelemy was responsible for a big part of that.

Salgado and his assistant started traveling together slightly after he began his project "Gênesis" in which he took pictures of some of the most remote people and places in the world in order to arrive at the most traditional kind of life possible.

Antarctica was one of the first places he visited. After staying at a British base, he started exploring - just him and his equipment: something he had been doing for decades.

When it's summer, deep cracks begin to form along the icy surface of the world's southernmost continent. The untrained eye, however, may not be able to tell the different shades of white apart from one another, meaning one could easily fall into one of the crannys and get shredded to pieces. That's why members of an expedition tie themselves to one another: if one person falls in, the others can pull him back out.

One day, a group came by on a yacht, not far from Salgado. They went out on an excursion. A while later, one of the members from the group ran over in desperation, saying that their leader had fallen into a cranny. "Temperatures in the summer vary from -6ºC to -10ºC in Antarctica. But at the very bottom of these crannies it can get much colder. The man died, not due to the fractures, but due to hypothermia", Salgado explained.

The adventures he faced throughout the elaboration of "Genesis" led the photographer to realize how easily he could succumb to an unpleasant accident in some environment unfamiliar to him. That's how the photographer teamed up with the steadiest of his producers.

INFINITY COVE

Perhaps one of the most remarkable items on Salgado's list of equipments is the portable studio that enables the photographer to set up an infinity cove in the middle of the jungle. Though it may sound like a heavy structure, it's actually not. Akin to the Egg of Columbus, it's actually a simple solution and of the utmost importance when it comes to elaborating the series of portraits the photographer produces.

On his trips, Salgado always brings a kind of canvas sheet that trucks typically use to cover cargo. The long, brown 9m x 6m (54 m2) sheet can be folded up into a big backpack. In order to get the cove set up, he tries to use something similar to a goal post, like a tree, or he might carve out a wooden stick. The canvas sheet is attached to a "post" and covered with an impermeable plastic sheet so as to keep it dry.

Whenever he wants to use his studio, he rolls out the canvas sheet. In order to set up his cove, he attaches one corner of the sheet to the post while stretching out the sheet and attaching the other three to the ground. In Salgado's black and white pictures, the color that the cove gives rise to is similar to the green forest. The lighting is natural and sometimes it gets filtered by the treetops, producing a peculiar zebra-like effect.

{{imagem=30}}