SOUTH OF THE BORDER

Expectations and Resentment Torment Those Who Are Left Behind

26.jun.2017 - 02h00

{{video=4}}

The wall that Donald Trump promised to build during his campaign has yet to be constructed. But for decades, Mexicans have had to deal with the fences erected by Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton.

Maintaining the physical divide separating the US from its poorer neighbor has been federal policy ever since Clinton began building first stretches of the border fence in 1993, taking advantage of wastelands that were brought about by the Gulf War. 1,046 kilometers worth of barriers have been built along the border, including stretches where the 4.6 meter-high fences implemented by Obama - a fellow party member - prevail.

{{imagem=1}}

As a general rule, the border wall tends to be higher as it passes through more populated areas. It separates cities like the two Nogales: one Mexican, one American. It's lower or non-existent in inhospitable areas where people die daily, after a several-days-long journeys along the desert's natural barriers.

{{info=6}}

The wall is not just a physical one. Mexicans have also started to resent harsher immigration laws and surveillance, especially after September 11th. Trump's promise to crack down on illegal immigration has more to do with intensification than an actual policy shift.

"Trump frightens us and is unpredictable, but one must remember that Obama was also very cruel and rude toward immigrants. He signed off on 'redadas' [huge operations that led to the capturing of illegal immigrants], mass deportations, the practice of dividing families and creation of detention centers. He built this wall here and deported the most people in US history. He never said much, but did a whole lot", said Javier Calvillo, 47, a priest and the director of the Immigrant shelter in Ciudad Juárez, his hometown.

{{mosaico=6}}

{{imagem=24}}

{{imagem=25}}

"My greatest fear is that Trump will build a wall in the minds and hearts of Americans and even Mexicans who live there. That's the most dangerous wall: that's how racism and pointing fingers start. In El Paso, people are afraid of going to school, to work. It's a terror and panic-ridden environment", he said.

Even during the Trump administration, Obama's border wall continues to expand in the Ciudad Juárez region, replacing a low and inefficient fence.

Construction is currently taking place in Puerto de Anapra, a neighborhood with dirt roads and unfinished houses, a 30-minute ride from the downtown area of Juárez - a city of approximately 1.5 million inhabitants that was once considered the most dangerous city in the world, particularly due to turf disputes between drug cartels.

{{mosaico=1}}

{{mosaico=2}}

{{imagem=23}}

Anapra mainly houses employees who work for maquiladoras, the big, mainly North American factories that have set up shop in Mexico because of its cheap labor.

In Juárez alone, the companies employ around 300,000 workers.

The barrier is being constructed at a significant rate: every 30 minutes a crane adds to it a new 5-foot-wide sheet of metal that gets cemented before construction workers - most of whom are Mexican - reinforce it by welding it together with another sheet.

"I don't like working here, but I have to feed my family", said a construction worker who worked for a cement supplier and identified himself as Marcos. He said that his parents live in Juárez, but that visiting them was getting more and more difficult due to increased border patrol - it typically takes around two hours to cross one of the international bridges.

{{video=3}}

Leftover construction material quickly became a source of additional income for residents. Worker Fabiola Vellez, 31, hauled a long steel pipe over her shoulder, saying that it was worth around 50 pesos (US$ 2.80, or R$ 9.30).

The extra income only slightly increases her one-thousand-peso-a-week income (US$ 56, or R$ 190) which her employer, a factory that makes car cables, pays her. Just across the border, in Texas, the minimum weekly wage is US$ 290, or five times what Ms. Vellez makes.

Despite the extra income, Ms. Vellez isn't happy: "In December 'la migra' (the US border patrol) tossed toys over the fence. With the wall that will no longer be possible," she complained.

Children, who are also attracted to the region, stuck their arms through the fence asking for dollars and candy.

An audacious teenager showed reporters that he could climb to the top of the fence in a matter of seconds, irritating a nearby worker who was cursed at in Spanish after he said he would tell the teenager's mom.

{{imagem=11}}

The barrier got the best of José Hector Nevarez, 33. After being detained and getting deported from the US for the first time in 2010, he tried to re-enter the country twice during the Obama administration, but was caught both times by the US border patrol.

{{imagem=26}}

After giving up on plans to move back to the US, Hector, who was accompanied by his wife Gabriela, 32, and his two children, Emiliano, 12, and Azul, 7, decided to reconnect with his family in Mexico. He left them when he was 15.

The border wall has picked Hector's family apart. The story repeats itself frequently: while many parents are Mexican, their children have American citizenship because they were born in the US.

In the case of Hector's family, as well as several other deported families, the solution was to move to the Puerto Palomas village - 157 kilometers from Juárez. Every day, while the parents go to work in Mexico, their children cross the border and go to American schools in New Mexico.

"The US is their country. When the time comes, they'll get a job there, they'll have a social life there", said Hector, who worked in civil construction and as a driver in the US. "We want them to live their lives there. And, obviously, if we get the chance to visit them, great, but we can't live there."

{{video=1}}

Weekdays begin early for the Nevarez family, at around 6am, when the temperature tends to be in the single digits. First, Hector takes Emiliano to the border checkpoint. His son is alongside him as they walk on American soil for several feet, until they reach Immigration. "If they want, they can arrest me for being here."

Hector, who is standing next to other parents who were also deported, watches as his son gets on one of five yellow school buses lined up just past US Customs. An hour later, he repeats the procedure with Azul.

After school, it's Gabriela's turn to wait for her children at the Mexican checkpoint where their backpacks have to go through x-ray machines.

{{mosaico=4}}

{{imagem=15}}

The border comes with its share of dangers. The precautions Hector and Gabriela take by accompanying their children to the checkpoint are a form of making sure they don't get accosted by drug dealers trying to circumvent US Customs.

"Unfortunately, we live in a country where there's a lot of crime. There are cases where kids are used as mules and they wind up detained by Immigration. We always make sure they aren't packing anything other than their school supplies in their backpacks".

The border can also lead to financial opportunities. Hector works at a traditional restaurant called Pink, which is right next to the border, and a popular option among Americans who cross over to Palomas in search of Mexican dentists and eye doctors who cost a fraction of what their American counterparts cost.

{{info=7}}

Back at home, Gabriela supplements the household's income by giving baths to dogs. Her clients are American and they drop off and pick up their pets in the small neutral zone in between the two countries' checkpoints.

The border also gives rise to peculiar situations. Since moving to Palomas five years ago, the couple has never visited their kids' school - they saw their son Emiliano graduate from elementary school via Skype, which is also how they communicate with teachers. "But we feel very lucky. [Studying in the US] is a privilege that not everyone has", said Hector.

{{video=5}}

When it came to Donald Trump, Hector was skeptical. "He's saying what people want to hear. He says he's going to build a huge, big, extravagant wall, but it isn't going to happen. He's a talker."

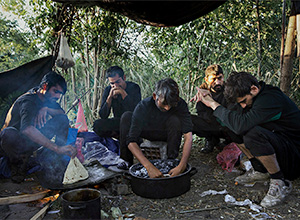

Caborca, which is 680 kilometers west of Juárez, is the last stop for many Central Americans before they risk crossing through the wall-free desert. It's also where almost every day dozens of people hop off "Bestias" - a nickname given to any train that crosses Mexico and that immigrants dangerously and illegally take advantage of to get close to the border.

Right next to the train station there's another Immigrant shelter that housed 57 immigrants back in April, most of whom were from Honduras. Among the predominantly male group were immigrants who had already been deported, but would pick Trump's America over the poor and violent Central American countries anytime - especially Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

{{imagem=16}}

In contrast to Juárez, the shelter in Caborca was precarious. Most people slept outside, curled up on top of rugs, under canvas roofs, despite the cold early desert mornings. Garbage would start to pile up, leaving a bad smell in the air.

The stories they told revealed the struggles of border crossing. One man said he was forced to drink his own urine after an unsuccessful five-day journey. Another said he had to return after getting infected from tick bites.

Crossing over illegally is both expensive and dangerous. Coyotes charge two different rates. They typically charge US$ 8,000 (R$ 26,000) to cross, but will charge half price if migrants decide to carry a backpack filled with drugs over the border.

{{mosaico=5}}

Emir (a pseudonym) who was one of the few first-timers, is a 30-year-old from El Salvador who took 45 days to get to Caborca. He claimed to have taken 15 trains. "It was difficult, and there were moments I'll never forget. I met a girl who lost a leg trying to hop on the train."

Emir is waiting for the right moment to risk everything and cross the desert, and said he's not afraid of Trump's stance on immigration. "No US president hasn't deported people".

{{info=2}}

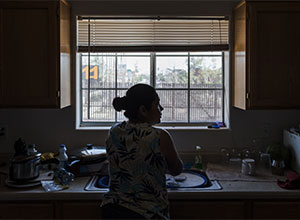

The barred fence spreading across the border lends it the quality of a prison, as families reunite on a daily basis on opposite sides of the Obama-sanctioned bars that separate the Mexican Nogales from the American one. The families exchange food, gifts and news as they chat and try to touch one another.

Standing at an incline, in the dirt, the 47-year-old cleaning lady Aída Laurean, who was on the Mexican side, stayed with her daughter Sofia, who was on the American side, from 11:30am to 6:30pm.

The two of them went their separate ways when Aria decided she couldn't miss her mother's funeral in Mexico, even if it meant not being able to return to the US.

She made it to the funeral on time, but spent the next seven years without seeing her daughter.

{{imagem=19}}

The border is intimidating. Sofia, who is a telemarketer only decided to risk getting close to it after she started carrying her provisional resident card, which she got after marrying her Mexican-American husband. However, she can't leave the country until the process is over.

"They're saying he wants to build a new wall. I hope it's a low one, so I can jump over" Aída said playfully of Trump.