IN THE LAND OF TRUMP

North of the Border, the Past Heats Up and the Future Looks Intimidating

26.jun.2017 - 02h00

{{video=2}}

Over the past three years, Maria de Lourdes Mendoza had gotten used to having her meetings with her son, Ramón, 27, timed. First, in prison, after he was arrested for drugs in San Diego, California. Later, in court, shortly before he was deported last February.

One Sunday at the end of April, the cleaning lady had a chance to hug her son again. They had three minutes observed by agents of the Border Patrol, who temporarily opened up a rusted gate in the fence that divides the United States and Mexico on the far west point of the border, on the coast.

In tears and in front of journalists, she told Ramón that she loved him and asked him to take care of himself. He told her not to worry any more.

{{mosaico=1}}

{{imagem=22}}

That same day, another five families were able to touch each other more than is generally allowed by the gaps in the fence that traverses Friendship Park between San Diego and Tijuana.

These events are organized at least once a year by the NGO Border Angles, with the approval of the Border Patrol, which verifies family history. Only immigrants formally registered in the US can participate.

"Hugging your son is something priceless," said Maria de Lourdes, 50, three days later, in the house where she lives with her husband and her daughters aged 30 and 19, in San Diego.

In tears, she recalls that the family had never been divided before Ramón's deportation, who now lives in Tijuana with cousins and uncles. Today, mother and son are separated by a 35-minute car ride and a border.

{{imagem=4}}

Only the youngest daughter, who was born in the US, can visit her brother on weekends.

"At the immigration holding facility [while Ramón was detained], we could eat with him for one hour every weekend. Now I can hear him over the phone. Knowing that he is all right, working, is a comfort to me."

Despite the suffering caused by their separation, the Mendoza family is not thinking of going back to Mexico, like thousands of families divided by the border. In most cases, the reasons cited for staying in the United States can be summed up in the word "opportunity": to work and live.

{{info=1}}

Maria de Lourdes and her husband had illegal status for more than 20 years, and today they have a "U" visa for victims of criminal activity. Although it allows them to remain in the US, the document does not guarantee their return if they cross the border.

{{mosaico=2}}

{{mosaico=3}}

{{mosaico=4}}

{{imagem=13}}

She hopes that her lawyer's prediction is correct: that the "green card" that will guarantee her permanent residency status will arrive in one year. And she prays that Donald Trump will not make the process more difficult.

"God will soften the heart of that gentleman so he will see that immigrants are hard-working people."

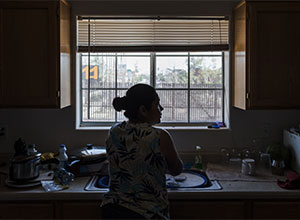

1,200 km from there, in El Paso, Texas, Cecília Martínez, 44, exhibits less faith and more fear about the future.

{{imagem=23}}

She is Mexican, also works as a cleaning lady, and has been living illegally in the US for 13 years. A few months ago she sought out a lawyer to draw up papers to give her parents, both permanent residents, temporary custody of her daughters, Cecília, 13, and Esmeralda, 8, if she and her husband are deported.

"The girls cry, they're afraid that they will separate us. It's very painful. I want to be here, I want to be the one to raise them."

The couple left Ciudad Juárez to escape from violence and look for better jobs. Today she says she is only thinking of the future of her daughters.

Since February, when the Department of Homeland Security expanded and accelerated the policy of deportation, Cecília has been avoiding going out in the street and only drives if it's urgently necessary (roadblocks are a common method for catching undocumented immigrants)

{{video=5}}

"The immigration agents' attitude has changed, it's more aggressive and intolerant. They feel they can go into any community out of the blue and just start demanding people's documents," says Fernando García, Director of the Border Network for Human Rights. He is Mexican, and has been living in El Paso for the past 25 years.

His NGO has performed role-playing exercises in the homes of immigrants on how they should react if an agent of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) knocks on the door.

{{imagem=16}}

{{imagem=17}}

"You have a right to prevent them from entering your house without a warrant, and to remain silent. You can also ask for a lawyer, and you are not required to sign your deportation papers," explained Margarita Arvizu, one of the network's volunteers, to 14 immigrants one April afternoon.

The number of deportations per month, since Trump took office, is less than the last three months of 2016, when Barack Obama was in power. In May, there were 14,786, the lowest monthly average since 2003, under George W. Bush. Obama broke the annual record, with 410,000 deported in 2012 -34,000 per month.

{{info=2}}

{{imagem=24}}

Housewife Rocío Orozco, 42, decided not to take a chance in the last 20 years. In this period, she and her husband have lived apart - she in Mexicali, Mexico, he in Calexico, California.

Rocío saw Alfredo and her children James, 20, and Melanie, 17, born in the U.S., on weekends, when they went over to the Mexican side.

Only in September, when she got her "green card," was the family reunited. Living just meters from the chain-link fence that separates these symbiotically-bound cities, today she sees Mexico from her window. She loves to listen to the mariachis playing at the restaurant right next to the border.

{{imagem=14}}

From her window, almost every day, Rocío also sees immigrants approaching the 5.5-meter fence with an improvised ladder to jump over to Calexico. Most are caught by the border patrol before they can manage to escape.

"When I see people caught by immigration, it makes me sad, because they want an opportunity but they're not going about it the right way. Many of them don't have a chance to."

The significant drop in the number of detainees since the beginning of the Trump administration suggests that fewer people are trying to enter the US illegally. The 52,347 detained by the Border Patrol from March to May are nearly a third of the 150,061 for the same period in 2016.

Rocío says she cannot imagine what will happen to the populations of the two cities if the fence, built in 1999 to take the place of a barbed wire barrier, is replaced by a closed wall.

{{info=3}}

Trump has promised to construct a wall along the entire extent of the border, without explaining its form, or how it will deal with rivers and mountains.

Presently, 1,046 km of the total 3,200 km of border between the US and Mexico already has some kind of fence.

{{imagem=18}}

"It would be some kind of Berlin Wall, because we wouldn't be able to see each other. Now families have a chance to greet each other, even from a distance."

It is not known, however, whether the US Congress will approve the budget of US$ 1.6 billion to begin construction of the wall. Before the end of this year, companies interested in the project can start to build prototypes near San Diego.

Barriers that divide urban centers are now appearing, with tall steel columns, between which people can pass their hands and sometimes their forearm. Border Patrol Agents monitor interactions.

In San Diego, there is a double fence on 20 of the 74 km where there has been some construction.

"The second fence gives us time. If someone jumps the first one, they still have to cut [the wire] or jump over the second one," explains Eduardo Olmos, head of communications for the Patrol in San Diego, observing the bustle of Tijuana from the top of a mountain.

A little farther away from the cities, the fence disappears or gives way to barriers with more gaps, where empty water bottles and cookie packages left behind give evidence of the entrance routes of irregular immigrants.

{{mosaico=7}}

In Tornillo, 60 km from El Paso, there are 15 km with no fence. "I think they ran out of money," says Jim Ed Miller, 68, owner of cotton farms whose boundaries merge with the border.

With a gun at his waist, a neighbor who goes only by the name of Andy complains that the region is less safe because there is no barrier. "They've tried to steal my machines, that's why I go armed, and I have to protect my mother," he says, surrounded by his dogs, who growl at the slightest movement.

Folha waited for nearly an hour without seeing any Border Patrol agent at a spot where a shallow ditch and some bushes are the only obstacles to anyone wishing to cross over. From there, many immigrants follow a dirt road for no more than ten minutes, until they reach a state highway where, frequently, they are picked up by coyotes.

{{info=4}}

Confronted with criticism, the patrol responsible for this sector said they use different methods for vigilance, and have seen a "significant reduction" in illegal activity in the region.

The number of detainees in El Paso in 2016, however, was the highest since 2008, 25,634. In the last three decades, the region has declined from second to fifth place in the flow of immigrants.

In San Diego, which was the champion for detentions in the 70s, 80s and 90s, coyote operations have declined with the building of the second fence and the implementation of technological vigilance systems. In response, the valley of the Rio Grande, in the far south of Texas, became the main route: 187,000 immigrants were detained here in 2016, or 46% of the total.

{{info=5}}

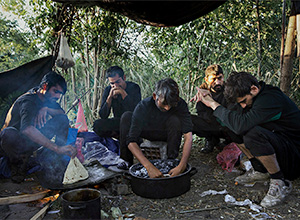

Mexican Joel Olivas, 28, was one of the 63,397 captured by the Border Patrol in the region of Tucson, Arizona, in 2015. He crossed the border with five other immigrants, all of them carrying drugs.

Folha met him the day after he left prison where he served a 2-year sentence for drug smuggling in Nogales, Mexico, which has comprised the boundary with a city of the same name in Arizona ever since the US-Mexican War split it in half in 1846.

"There are times when you have to take a chance to improve the life of your family, but knowing that you're going to sacrifice many things. I sacrificed seeing my son grow up. When I left home, he was eight months old," said Joel, who was trying to go back to Tijuana, where his wife, Alejandra, and Isaac, 2, live. "He hadn't started walking yet. Now I imagine he'll come running and give me a hug."

{{imagem=25}}

Joel says that he "did something bad," and says that he would not try to come in again with drugs. "But at that time, I wanted fast money. And for a lot of people, it works. I was unlucky, what can I do?

He remembers his despair when he realized he couldn't lift the bag that weighed nearly 50 kilos, including the marijuana he had received, US$ 1,800 to carry, and several bottles of water. He began by shoving it, then put it on his back and ended up getting used to it during the 5-day crossing.

"When the water ran out, I ended up drinking water from puddles, filtering out the mud. If it was really muddy, I just wet my mouth with it."

Along the way, he realized that traveling in a group attracts attention. When a plane flew over, everyone had to try to hide in the low scrub and stay for hours in the 40°C sun.

Crossing over alone is also risky. Without any cell phone signal in the region, many people spend days lost. Hundreds die each year. In 2016, the figure was 322 - 84 in the region of Tucson alone, where Joel went over.

{{imagem=15}}

{{info=6}}

Some have the good fortune to find bottles of water and supplies left along the way by organizations such as Water Stations, which maintains 160 stations with six gallons of water inside a plastic drum, marked by a red and blue flag that can be seen from a distance.

Resupplying is done every 15 days by John Hunter, the NGO's founder, his wife, Laura, and ten volunteers. And they have an extra job to do: restore the points destroyed by people opposed to providing assistance.

"It's terribly cruel to vandalize the water stations," Laura observes sadly. "To us, it's not a matter of immigration. It's a matter of life and death."