An ancestral conflict

A Barrier That Was Built in the Name of Security Segregates Human Lives and Memories

4.set.2017 - 02h00

{{video=3}}

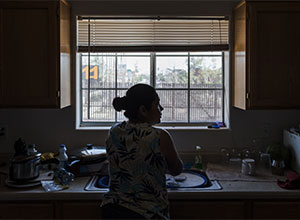

Umm Judah, 64, has forgotten many things. Among them, the word for something that has shaped the last few years of her life. The word she couldn't seem to remember was "wall".

The retired Palestinian school teacher lives on the outskirts of Bethlehem, in front of an eight-meter-high barrier.

The horizon outside her door is completely blocked out by the barrier, which separates her from the land she had cultivated for decades, as well as the memories she had of her sons glowing in the headlights, pleased with the figs they had just picked.

"It's like a blindfold", she told Folha. "It's like they pulled our eyes from our sockets."

Throughout the interview, she had to point toward the wall since she couldn't remember the term in Arab, her native language.

{{mosaico=1}}

{{info=1}}

{{imagem=30}}

The stretch of the wall in front of her home is but a fragment of a structure designed to span 764 kilometers, and that Israel has been erecting since 2002 in order to separate itself from Palestinian territory on the West Bank, which includes cities like Bethlehem and Ramallah. It is mostly made up of fences, while concrete is used for urban areas. Another 194 kilometers have yet to be constructed.

The wall has had a brutal impact on the lives of people like Umm Judah. But Israelis across the political spectrum agreed that building the wall was of the utmost importance.

The wounds left behind from the Second Intifada are still fresh in people's minds. Approximately 3000 Palestinians and 1000 Israelis were killed during the Palestinian uprising that took place between 2000 and 2005, against Israeli occupation. While Palestinians resorted to suicide bombers, Israel replied with tanks.

{{imagem=4}}

Ury Vainsecher, 71, an Israeli, remembers it all vividly. He had already moved to Kfar Saba, a city that is one kilometer away from the wall, and en route to the Palestinian city of Qalqilya.

"When my sons were younger, I'd take them everywhere by car. The thought of them on the bus scared me", he said. "Between getting blown up, and some Palestinian woman being surrounded by walls, I prefer the latter."

A friend of Mr. Vainsecher's died in a bombing, while the son of a neighbor died in another. An acquaintance of his who was at a pizza place also died after terrorists targeted the place.

{{info=2}}

The stretch of wall in front of Umm Judah's house was the latest to be added to the construction.

Up until a year ago, it took Umm a three-minute walk to get to her orchard, where she would lay under olive trees and role stuffed grape leaves. Now, it takes her forty minutes to drive to the other side.

"But the wall helped the Israelis. They're at ease."

{{imagem=5}}

The friction caused by the wall has disrupted the chances of reaching a peaceful solution anytime soon.

The construction has been criticized by figures such as Yossi Beilin, one of the architects of the Oslo Agreement (an agreement that determined different areas of control on the West Bank).

If the agreement hadn't been interrupted by the assassination of Israeli prime-minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was killed by an ultranationalist back in 1995, then it may have helped bring the conflict to an end.

"Of course the construction of the wall would humiliate Palestinians", said Beilin, in Tel Aviv.

"But the wall wasn't built out of malice, and there were attempts to reduce their suffering, even though they may not have been sufficient", he said, citing a series of appeals made to Israeli courts - six of which were successful - granting alterations in the route of the wall.

According to Beilin, walls "are not photogenic".

{{mosaico=2}}

{{imagem=10}}

{{mosaico=4}}

"They are very hard to explain. The walls have become a symbol of how we have forced Palestinians into a prison. It's their lives, and they are asking themselves why they are paying this price". After all, Palestinians on the West Bank were not only forced to sever ties with the lands they had cultivated, but their freedom of movement was also drastically reduced.

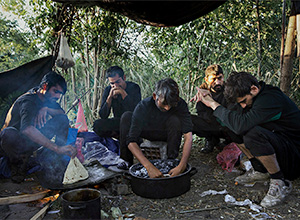

Folha accompanied the commute of Palestinian workers en route to Israel, who had to go through military checkpoints in Bethlehem and Ramallah.

By 5 am, the line had already extended beyond the metal corridors that were reminiscent of a corral, as rats traversed the filthy floors. Some were more anxious than others, so they climbed to the top of the fence and, like dystopian acrobats, formed a line that was parallel to the official one.

Thousands of people have to go through the ritual on a daily basis. "We have turned the lives of several Palestinians into hell", said Beilin. "But we have reduced the number of killings, so it's hard to say that it was the wrong decision".

{{imagem=25}}

From a legal standpoint, it is not wrong of a country to raise a wall along its borders.

But the border between Israel and the Palestinian territories is by no means conventional: after all, there isn't a Palestinian state. The frontier is referred to as the Green Line, which demarcates the perimeters that existed prior to 1967, the year of the Six-Day War, when Israel occupied the West Bank.

{{info=3}}

The plight that Umm Judah and others have had to put up with was worsened by the fact that, for every 6.5 kilometers of wall raised, 5.5 kilometers were raised inside of the West Bank, and, therefore, not strictly along the border. In certain stretches, the wall dips 18 kilometers away from the border and into the West Bank.

A lieutenant in the Israeli army, who preferred to remain anonymous, explained that, at times, the route had to be altered due to security concerns. For example, in certain situations, the wall had to be built on top of a hill as opposed to around it.

{{video=1}}

{{imagem=29}}

"Our experiences in courts are always the same", said Palestinian lawyer Dalia Qumsiyeh, who represents Umm Judah.

"The Israeli government just has to use the magic word 'security', and then they can approve their projects", she said.

"But before talking about security, they should think about the woman who can't access her land."

Or Hani Amer, 60, who is also a Palestinian and lives in the northwestern region of the West Bank, right on top of the line that the Israeli government had wanted to build the wall on top of.

Since he refused to leave his home, the border wall had to go around it and now his land, which has an area of 1000m², is surrounded by concrete, barbed wire and security fences.

{{imagem=17}}

The wall was built in order to protect the Israeli settlement of Elkana, which is a couple dozen feet away.

"They said that I could either leave, or be completely isolated. I decided to stay because, despite all the difficulties, this is my home", he said while sitting on a swing in his backyard - the wall literally right in front of him.

At first, Amer had to ask the Israeli soldiers to open the front gate of his home whenever he wanted to leave.

"Hosting people was a nightmare. It was collective punishment." With the help of humanitarian organizations, the agronomer obtained a small victory: the key to a small door built into the wall, which is what Amer currently uses to leave his home.

{{video=2}}

When Amer went to open the door to his home for Folha, he crouched behind a car so that Israeli police wouldn't see him –he's afraid of being retaliated for talking about his life to the press. He worries they may take the key to the little door away from him.

"I had so many problems that I can't even remember all of them now", he said, before listing a couple of them.

For example, when his son was three years old, he crawled under the fence, but his wife wasn't allowed to cross over and get him. The child was found on the other side and brought back home.

"I went up to the soldiers and I said: "You aren't humans. You saw my son and did nothing."

When he was remembered that Israel raised the wall in order to guarantee security for their country, Amer said that "what guarantees security is justice". "When you treat two brothers differently, there's no security. So imagine what happens with two different peoples".

Despite already being limited, the wall interrupted the little communication that did in fact exist between Palestinians and Israelis.

{{mosaico=7}}

Amer lives close to Qalqilya, which is where Israelis used to buy groceries before the Second Intifada.

He also lives close to Tzur Yigal, where Eran Landau, 64, a Uruguayan-Israeli lives. "My home was built by a Palestinian family", he said. "I have friends on the other side, despite having fought against them", Landau stated.

"The wall is disquieting, but either you protect your family, or you don't. I want to live a good life, and I want my daughter to live a good life, too. If she can go to a nightclub now without running any risks, I don't care what people say."

Landau is a member of the voluntary security task-force in Tzur Yigal, and keeps firearms, a helmet and a gas mask stored in an explosion-proof room. "I take an M16 assault rifle with me when I travel. They could attack me at any given moment with a Molotov cocktail."

{{imagem=24}}

{{info=4}}

The recently-elected mayor of Bethlehem, Anton Salman, disagrees with Landau's assessment. "I don't think it's a security issue. I think it's expropriation", he said, right by the wall that runs through the city. He lost some of his land, which remained on the other side of the barrier.

The deviations with regard to the Green Line have swallowed up 9.4% of the West Bank, a process that is being monitor by Dror Ekes, an Israeli and director of the Kerem Navot NGO. "We monitor the land that Israel takes from the West Bank to give to Israeli settlers", he said. The settlers he was referring to live on the West Bank.

"The wall was built in order for the settlements to expand. There's a correlation between the presence of settlers and the wall."

According to former-Israeli soldier Avner Gvaryahu, 32, the wall needs to be inserted within the context of a wider system: that of the settlements. "The government wants to diminish the number of Palestinians here."

{{imagem=26}}

Gvaryahu heads an organization called Breaking the Silence, which compiles testimonies from Israeli soldiers on violence in the West Bank. When he was a parachutist, he would take direct orders from the settlers.

"The goal of the system is to protect Israelis, but no one is protecting the Palestinians", said Gvaryahu. "There will never be a true sense of security until the Palestinians are treated with respect and dignity."

In the areas adjacent to the wall and fences are blockades designed to keep Palestinians out for security reasons.

"In certain areas in between the barriers, one can see wildlife appearing", said Etkes as he pointed to a pack of deer that strolled past the car used by Folha's reporters and crawled under the fence, heading toward the secluded land that practically belongs to them.

{{imagem=23}}

Umm Judah is afraid that the same thing will end up happening to her orchard, if the Israeli military decides that she can no longer go past the checkpoint by the border. "I feel like I've lost a family member. They stole my joy", she said as she wept.

She then walked to the top of a street in her village that enabled her to look over the border wall. When she managed to see her orchard - filled with apricots, peaches, pears and rosemary shrubs - she regretfully uttered the words: "I'm going to die here".