Segregation

Wall of Shame Separates Indigenous People From 'Gringos' in Lima

21.ago.2017 - 02h00

{{video=1}}

If he could walk to the mansion where he works as a groundskeeper, it would take Esteban Arimana five minutes to arrive from his own house. Instead, he spends some two hours on crowded buses in the packed streets of Lima.

The distance between the neighboring houses is imposed by the Wall of Shame, as the ten-kilometer barriers that cross the hills of the capital of Peru are known. Their construction began in the mid-1980s and they exist to separate the urbanized areas from the "young settlements" -the local euphemism for slums.

"It would be nice if they opened a door," says Arimana, who lives with his wife and three children, while his oldest son, aged 14, stands next to the wall –three meters high and covered with barbed wire. "But we are seldom heard as we live in poverty".

{{info=6}}

{{imagem=1}}

{{imagem=19}}

The family is a typical resident of Pamplona Alta, a group of slums named after the hill they were built on; 96,000 people live in the area.

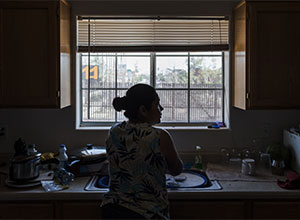

Their poor house made of plywood was built by the members of the family themselves on the rough terrain. There is no running water.

The bathroom outside the house is only a hole in the ground. A house in the area costs US$ 15,000 at most.

On the inside, Pamplona Alta is subdivided in different heights. The closer to the top and to the walls, the worse the houses are. Many of them were built on a landfill made of tires.

The dozens of kilometers of unpaved streets were made by the residents themselves who cut through the rock. Their method: using tires, they burned the base of the larger rocks, which cracked due to the high temperature and then were broken with hammers.

{{imagem=2}}

{{imagem=17}}

In the lower areas, where some of the houses already received official licenses as well as running water, some of the residents created local versions of private condominiums. To prevent their houses from being broken into, many residents have closed the streets using barriers tied to chains with locks.

In one of these older areas, a security guard in a cabin on the wall was watching to stop people from crossing into the rich side.

A few meters from him, a message was written by the residents of the poor side: "We do not accept pot smokers, thieves, gang members, drug dealers, etc. By order of community justice."

Arimana has lived in one of the unofficialized areas for ten years. A few meters above his house, the three-meter wall marks the limit with Las Casuarinas condominium, whose entrance is controlled by security guards and cameras at the foot of the hill - only residents and their guests are allowed to pass.

With a privileged view of Lima, there are mansions there that cost up to US$ 4.5 million.

It is in one of these mansions that Arimana works as a security guard and making small repairs. "I don't really have a profession. I can work in construction or whatever is offered to me".

Unlike the prices of the houses, water is more expensive on Arimana's side. Thus he and his neighbors must resort to getting their water from paid water trucks.

While water –stocked in plastic reservoirs– in Pamplona Alta costs some US$ 9 per cubic meter, on the other side the price of the running water varies between US$ 0.3 and US$ 1.5, depending on the range of consumption. That means the poor pay on average ten times more than the rich.

"On the other side, everybody has a swimming pool, while we suffer with water shortage," says Arimana. He adds that inequality in Peru is becoming worse.

{{mosaico=1}}

{{video=2}}

{{mosaico=2}}

{{imagem=5}}

Called "gringos" by their poor neighbors in a reference to their lighter complexion – tracing back to their European origins –, the residents of Las Casuarinas often sustain that the wall was built for security purposes and to stop land invasions.

Residents of Las Casuarinas include renowned chef and businessman Gastón Acurio, who has one of the houses closest to the wall. The son of a senator and educated in Paris, he is pointed as the main responsible for the popularity of Peruvian cuisine in the world.

By email Acurio says he does not agree with the wall, although he did not explain why. He says that he intends to open his second cooking school in Pamplona Alta for poor children in 2019 - the first was built in another poor area and teaches some 300 students.

"As businessmen and families, we try to act directly so that Peru can end once and for all the economic, social, cultural and physical divisions that have dishonored us for centuries," Acurio wrote.

Architect and cartoonist Carlín says the wall and the omnipresent fences in Lima are a consequence of Peru's widespread unemployment and racial inequality.

"The worst racism is that which people say doesn't exist," says Carlín, whose political cartoons criticizing Lima were collected and published in the book "Errar es Urbano". "We are one of the most racist countries".

{{imagem=8}}

As it has happened in other Latin American countries, the growth of Lima's population occurred mainly due to the expansion of the "young settlements," formerly called "barriadas".

In 1961, 17% of the population lived in slums in Lima. Data collected by sociologist Julio Calderón and published in the book "La Ciudad Ilegal," show that in the most recent census, carried out in 2007, this number reached 4.1 million, which corresponds to 40% of Lima's population.

{{imagem=21}}

Thousands of people came to Lima in the 1980s and 1990s looking for better economic opportunities and to flee the domestic conflict begun by the Sendero Luminoso Maoist guerrilla, concentrated mainly in the Andes.

The construction of the Wall of Shame followed the same pace as the expansion of the slums. The first part of the wall was built in 1985 by Imaculada Conceição school, run by Jesuits (the same order Pope Francis belongs to).

At the time, the school said the purpose of the construction –carried out without a license –was to stop the invasions from reaching the institution.

Now, in addition to the school walls and those of Las Casuarinas and other condominiums, there is a part of the wall built and monitored by the government.

{{mosaico=3}}

{{imagem=18}}

La Molina, one of Lima's 43 municipalities, built a stone barrier with barbed wire on top on the border of Pamplona Alta, which belongs to the city of San Juan de Miraflores.

The wall is not as high as that of the condominiums and has a passage, where there is a control station of the La Molina municipal guard.

The passage is used every day by residents of Pamplona Alta who work in La Molina, which has upper and middle class neighborhoods.

The way down is made on small paths along the steep hillside –unlike the poor side, there are no stairs here.

"From the border of La Molina on, it is a disaster," says Dionisio Chirinos, as he returned home after a day at work with his teenage son, whose knee was bleeding. "As you can see, my son has just hurt his leg".

{{imagem=14}}

{{imagem=20}}

Shortly before that, the news report team found the only resident of the rich zone who ventured into Pamplona Alta. A resident of La Molina, student Julio Díaz had climbed the mountain for exercise. Although he did not fear visiting the other neighborhood, he said he was in favor of having the wall.

"The wall is necessary to limit invasions. There is a lot of land trafficking. A handful of people take control of everything, divide it into lots and sell them to those in need. However, as we can see here, people are free to pass."

Folha contacted La Molina's press office, which only said that the barrier was built to protect the environment from further invasions; however, the office declined a request for an interview with one of the municipality's spokesmen.

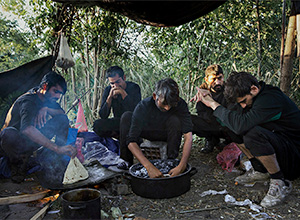

Some ten minutes from Pamplona Alta, one of the most recent invasions, conveniently named Valle Escondido, can be found at the highest point on the hill.

{{imagem=13}}

There, without electricity or running water and under constant freezing winds, families divided in two groups to fight for control over the region, creating an atmosphere of distrust.

One of the residents, who agreed to speak in anonymity due to the tense environment, explained why there was no wall there: "It is so steep up here that we cannot walk all the way down."