The voice of the hills

The favelas are part of the Rio de Janeiro landscape. They appeared following the first attempts to expel poorer citizens from more upmarket areas, and today the have spread all over the city. Take a look at the history of Rio’s favelas

Illustrations: Allan Rabelo

Script: Bruno Maron

Research: Bruna Fantti

Production: Eduardo Asta

Development: Lucas Zimmermann

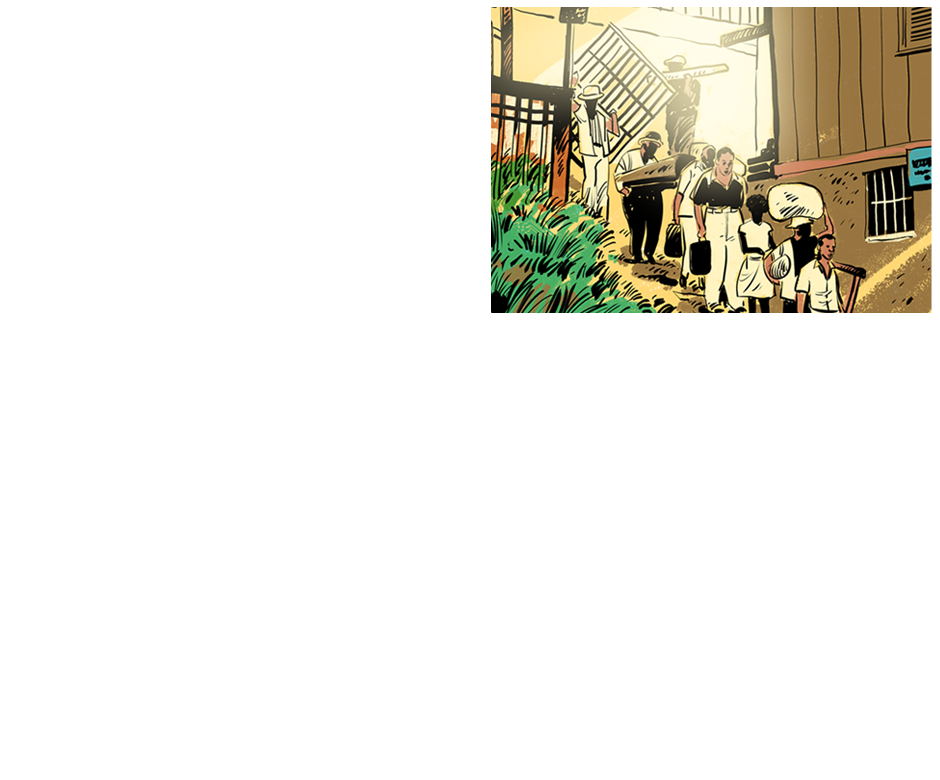

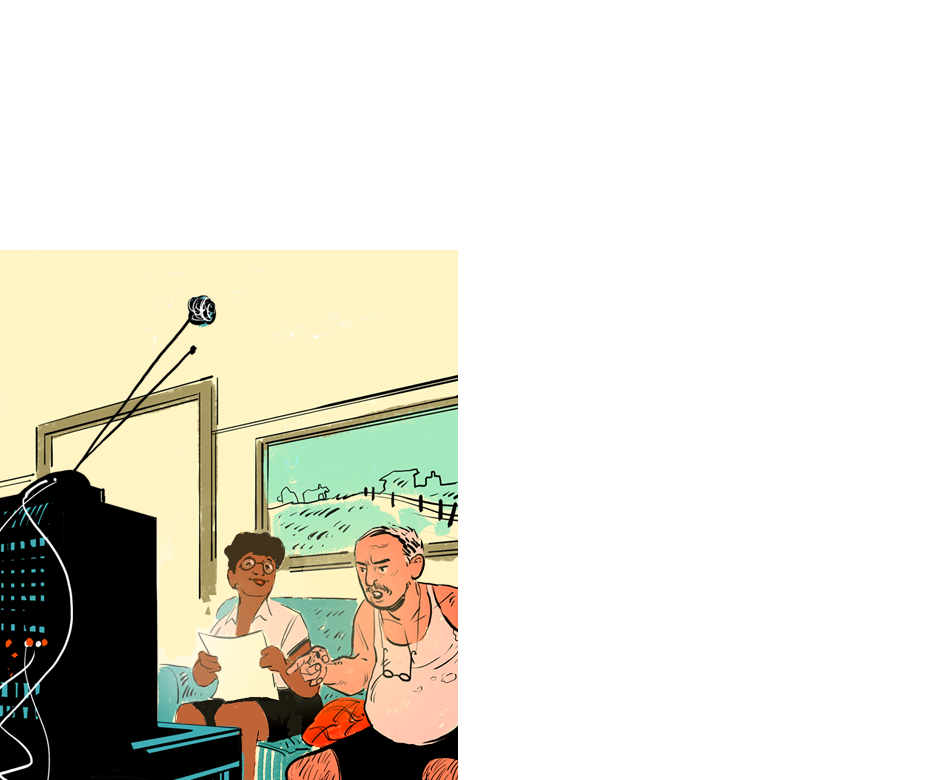

19th century: Brazil was one of the last countries to abolish slavery. Thousands of former slaves who had won their freedom had to find a new means of survival, and had to find space in the cities. This movement transformed the organization of Rio de Janeiro and influences the city until today.

Slavery was abolished in 1888. Without money or housing, the former slaves came to Rio, thousands of them coming from farms in rural areas in the state.

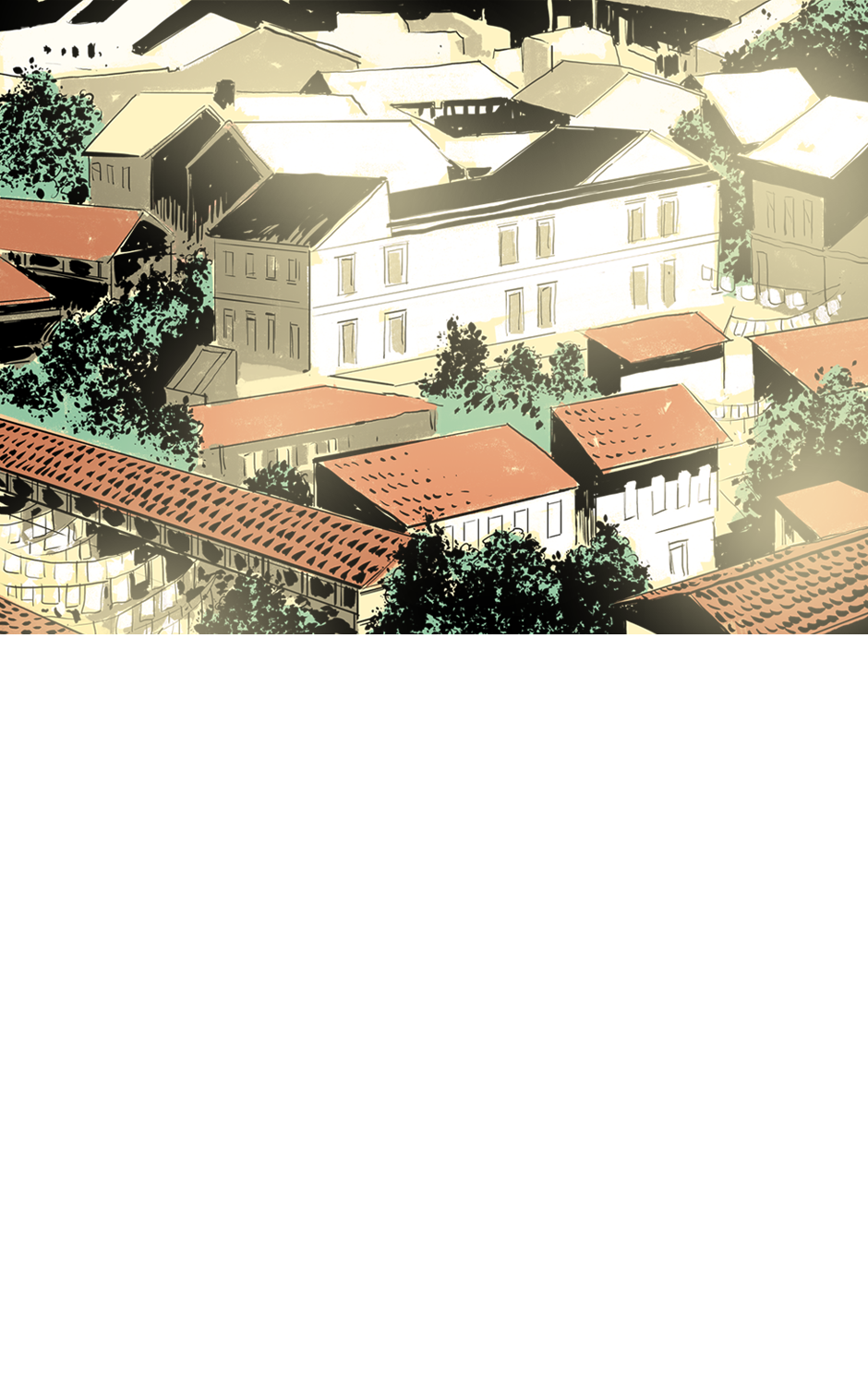

Their only option for housing were the cortiços, poor tenement buildings in which cramped dwellings were rented to entire families.

In an attempt to make a break with colonial Brazil, the government began a process of modernization following the Proclamation of the Republic in 1889. Old tenement slums were demolished.

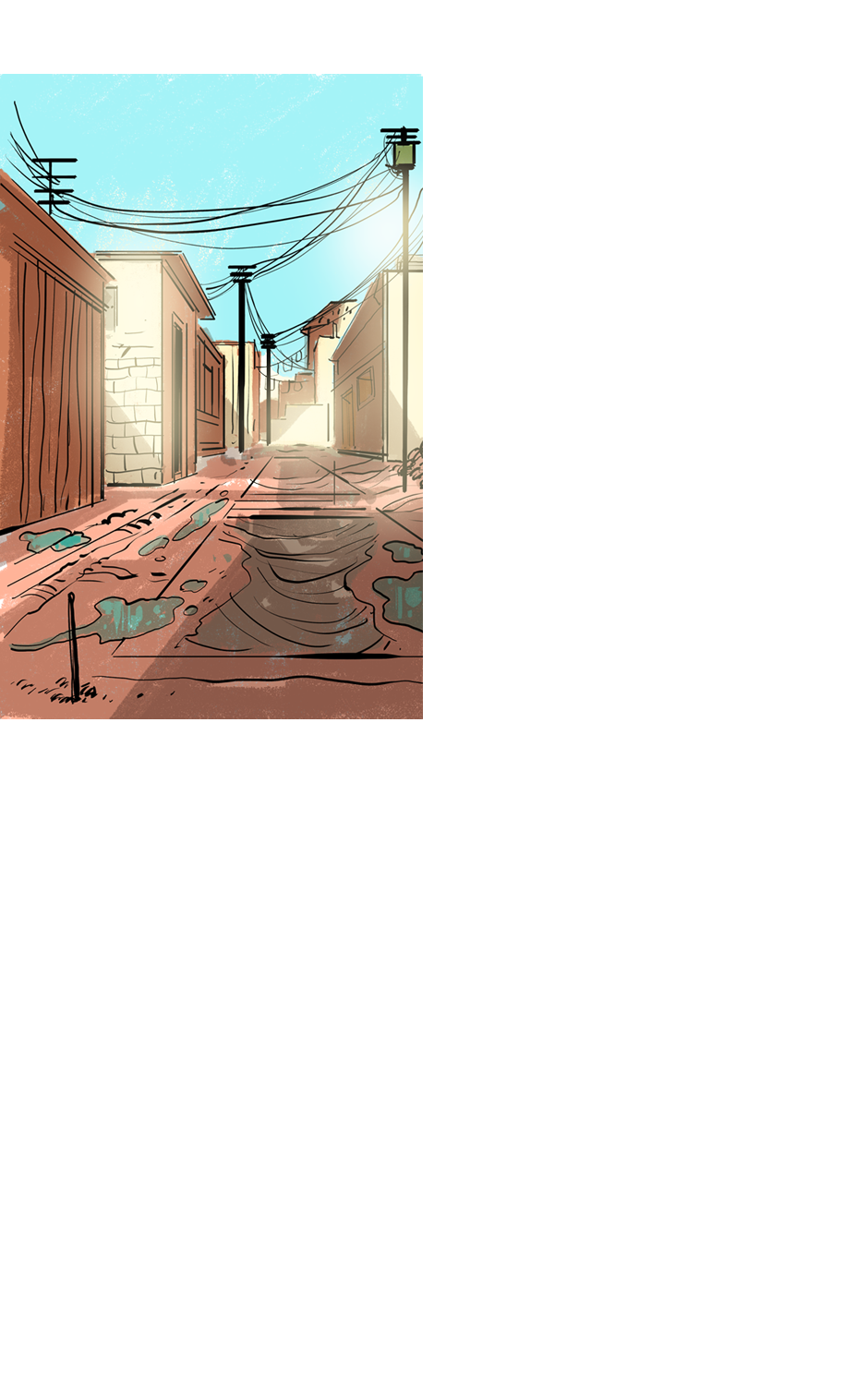

Well-known cortiços were demolished, such as Cabeça do Porco (“Pig’s Head”), which was home to 2000 people. In 1893, they moved to the Morro da Providência and Morro de Santo Antônio and founded the first favelas, building precarious housing from the debris of demolition.

In 1897, the War of Canudos –one of the bloodiest internal conflicts in Brazilian history– came to an end. A massive contingent of demobilized soldiers ended up without any money or employment.

Following a series of protests over wages that had been promised but were never paid, these soldiers also began to occupy the Morro da Providência, which by this time was already home to a large community of former slaves.

Morro da Providência

General Police Headquarters, 1900

After arriving in Rio in 1897, these soldiers began to refer to the Morro da Providência as “Morro da Favela.” Favela is a kind of plant that grew on a hill on the outskirts of the city of Canudos, where the soldiers had been fighting.

Cnidoscolus quercifolius

The housing crisis caused by the demolition of the cortiços became increasingly intense. An ever-greater number of homeless people began to seek refuge on the Morro da Providência.

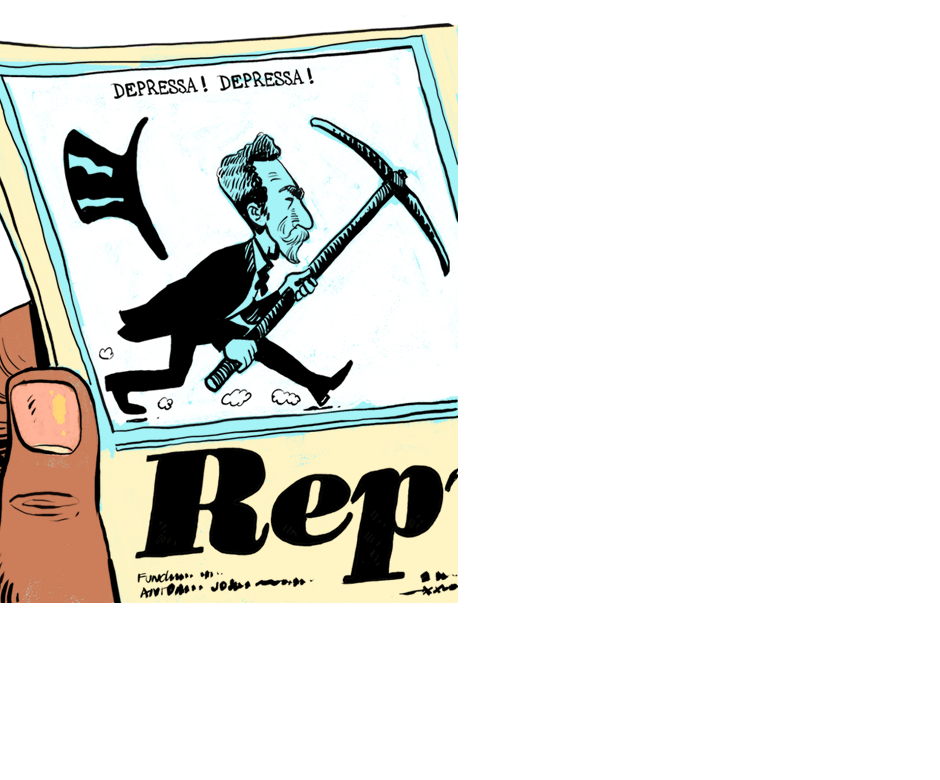

Demolish! Build! Modernize! Rio de Janeiro of the 20th century followed the trend of the world’s large urban centers. In 1903, Mayor Pereira Passos began a program of urban reform popularly known as “Bota-abaixo” (“Tear it down”), widening avenues and demolishing houses.

Lack of housing and high rents forced people into the favelas. The media described them as unhygienic and dehumanizing places.

Writers like João do Rio, however, tried to challenge this stereotype. He championed the cultural wealth of the favela, as in a short piece of writing from 1911 about the “celebrated hill” of Santo Antônio.

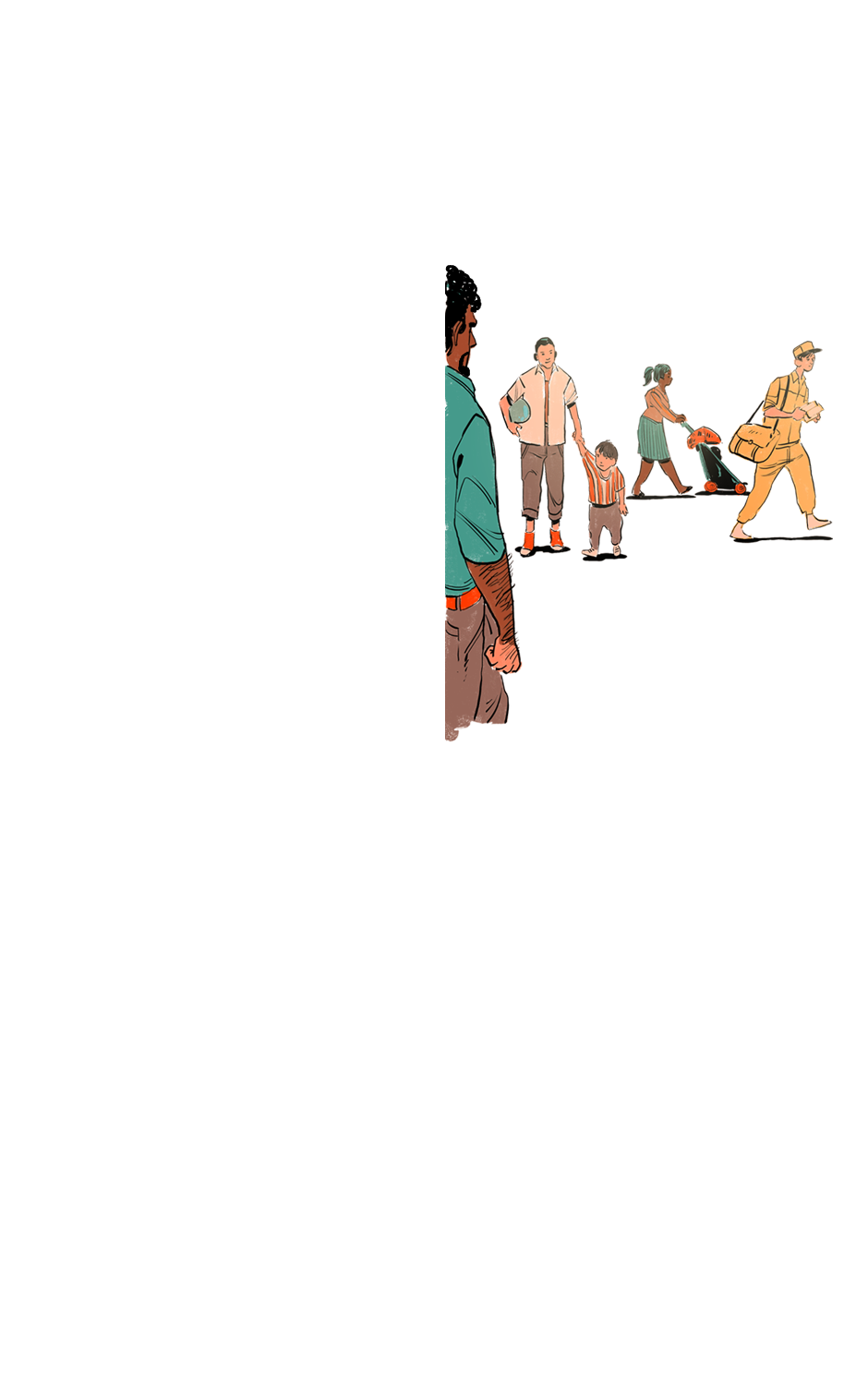

Needing to stay close to their workplaces, and given the limited public transport available, the poor began to occupy favelas downtown and in South Rio, the only districts with trains and streetcars.

Castelo

Morro de Santo Antônio

Morro da Providência

The map of Rio de Janeiro was gradually changing. Iconic favelas appeared, such as Mangueira.

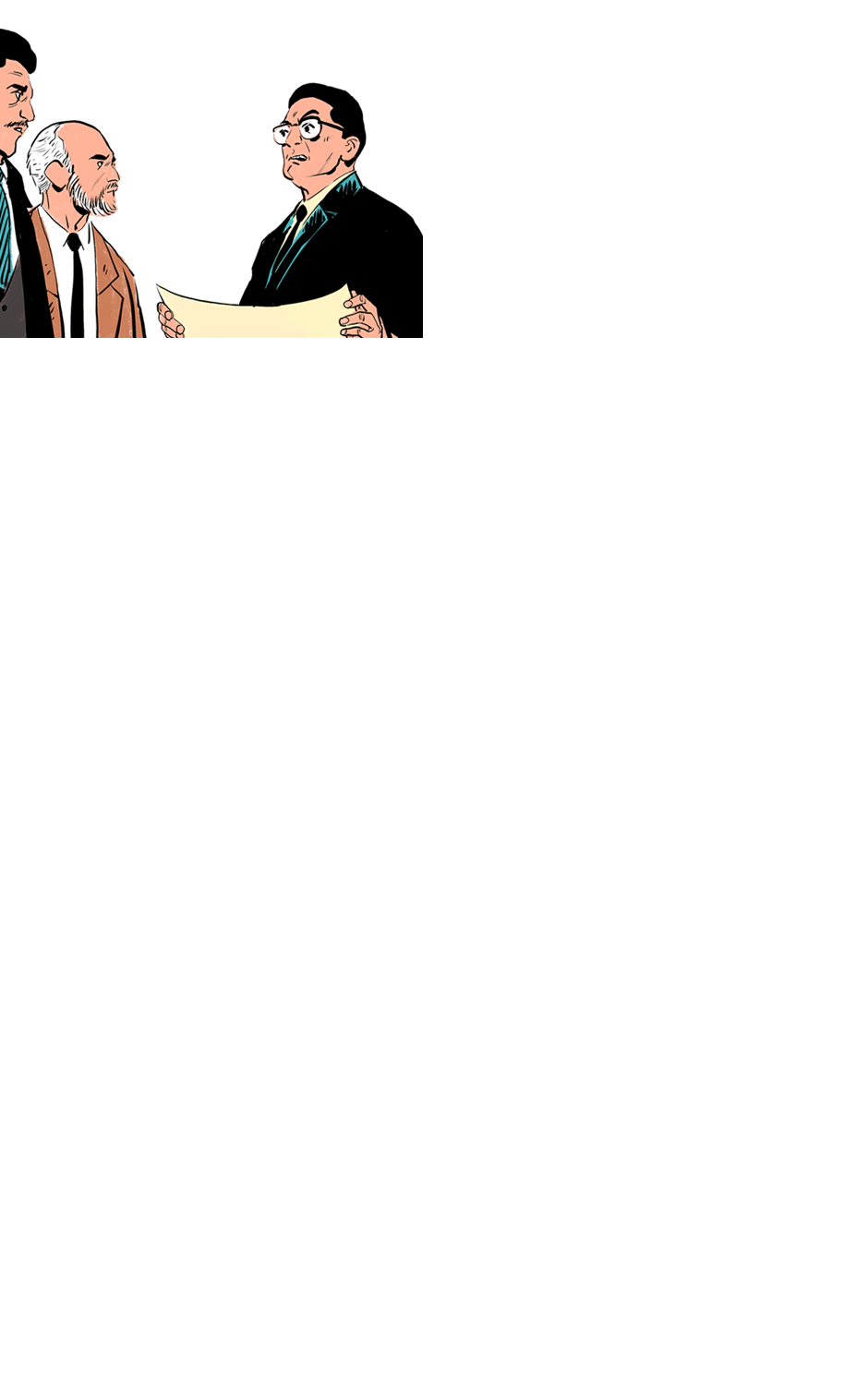

In 1937, the Vargas administration began an aggressive phase of forced removals that would forever mark the residents of Rio’s favelas. Relocation and provisional housing programs began to pop up all over the city, creating animosity between the authorities and evicted favela residents.

Some projects, such as Parques Proletários Provisórios, in the 1940s, and Cruzada São Sebastião, in the 1950s, provided housing for favela residents; 17 favelas in the Lagoon district and in the downtown area were destroyed to make room for such temporary social housing.

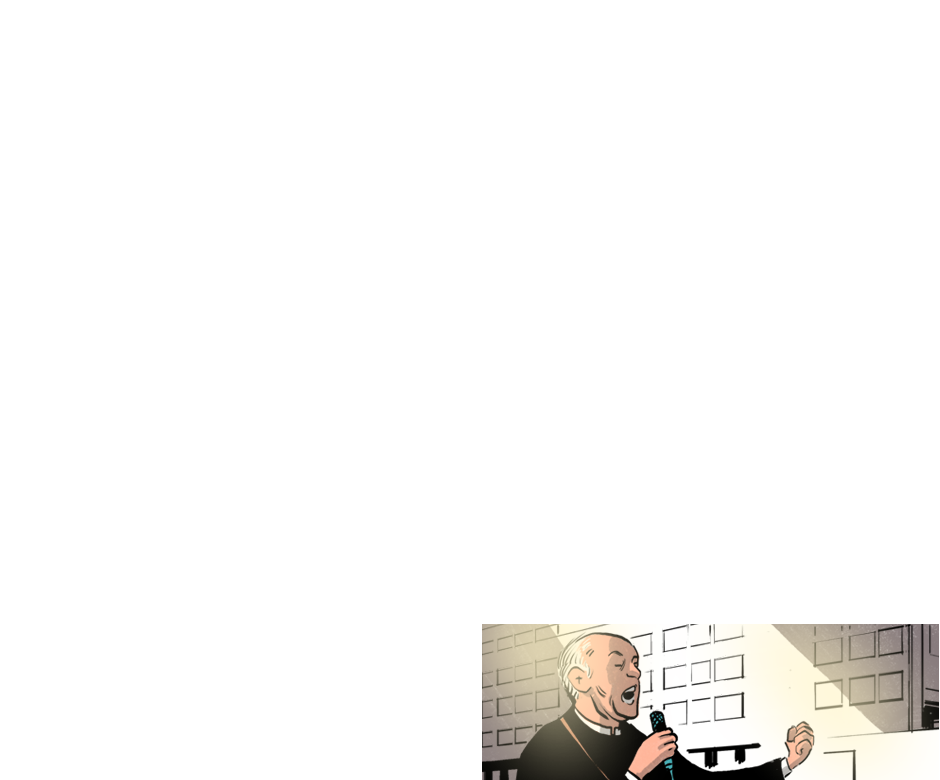

The Cruzada São Sebastião, led by the then Auxiliary Bishop of Rio de Janeiro, Dom Helder Câmara, created a social housing project in Leblon in 1955. This was the first attempt to house evicted favela residents close to where they had been living. The model also strengthened the notion of community, which was fundamental for residents’ sense of belonging.

We are a community!

The 1960s was marked by the consolidation of an anti-favela movement. It was led by Carlos Lacerda, the first elected governor of what was then the State of Guanabara.

Result: the destruction of 27 favelas, and the removal of more than 40,000 people to other areas of the city. New social housing projects were built to house them.

The aim of these policies was to occupy Rio’s suburbs with industries and housing for the poor.

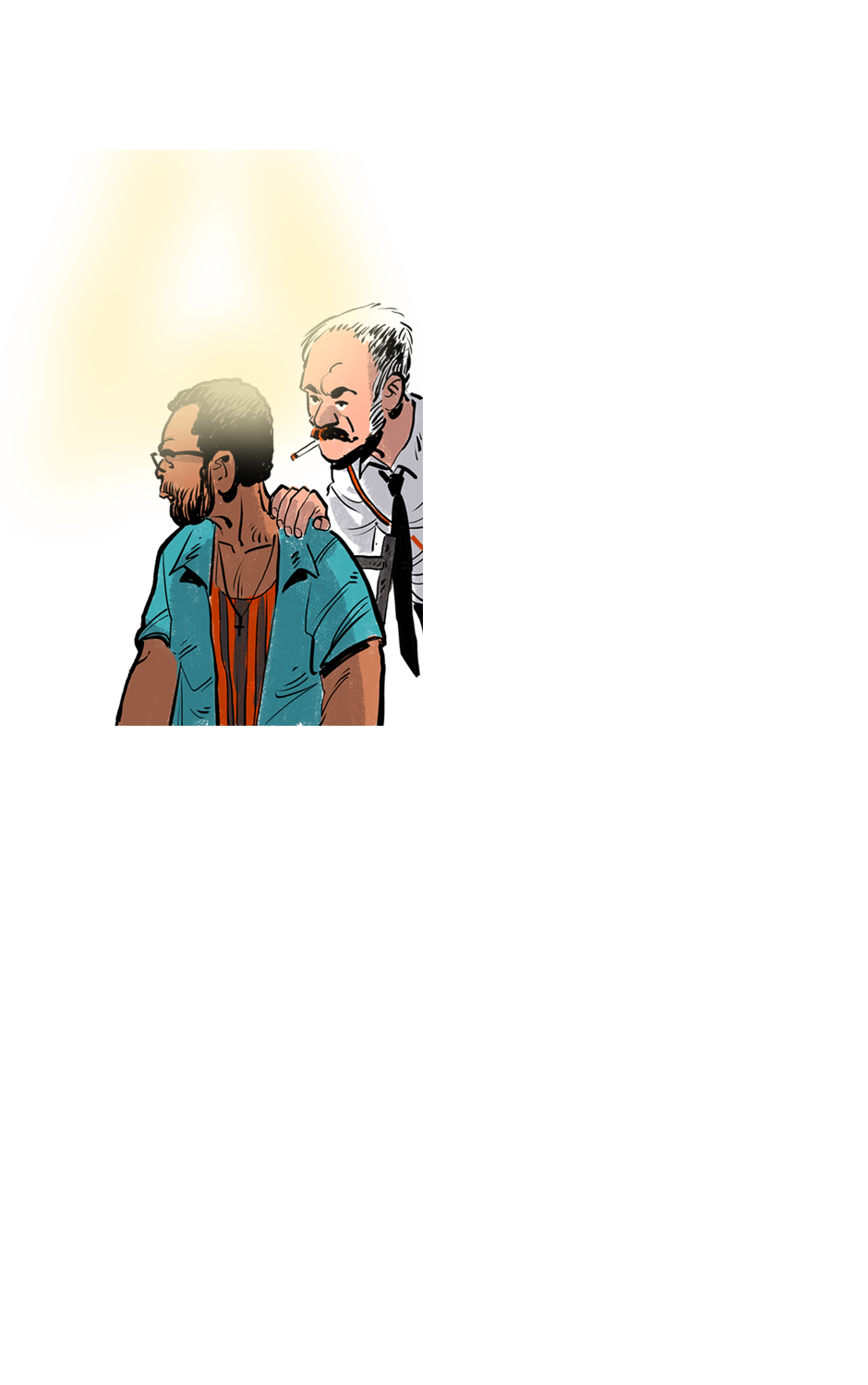

The removals policy reached its peak during the military regime. The favelas resisted, with the main leaders being either co-opted or crushed.

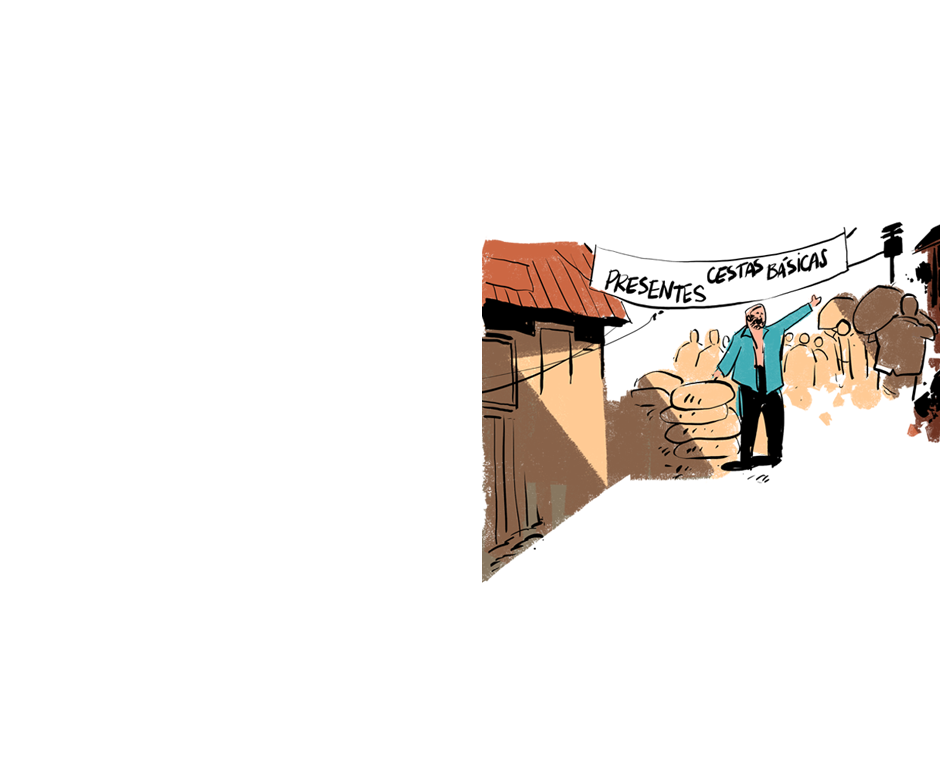

From 1975 onwards, the removals policy lost momentum, mainly due to the financial problems of the National Housing Bank (BNH), which had been financing housing programs. This withdrawal of government encouraged clientelistic relationships between favela residents and politicians.

I’ll protect those who vote for me!

With the 1980s, the devastating force of the drug trade arrived in the favelas, the first serious consequence of the vacuum left by the state’s withdrawal from these communities.

Using techniques learnt from political prisoners whom they lived alongside in prison, drugs traffickers formed the Comando Vermelho (“Red Command”), a criminal organization that dominated the Rio drug trade until the 1990s. They used complex international trafficking routes and heavy weaponry, and became famous for daring escapes from prison.

Escadinha

Get away!!

By the early 1990s, cariocas had already become used to expressions such as “stray bullet” and “risk area”, terms that referred explicitly to the issue of urban violence. This was now invariably identified as the main problem caused by the favelas.

…a stray bullet from an AR-15 rifle…

That’s a weapon from the Israeli army!

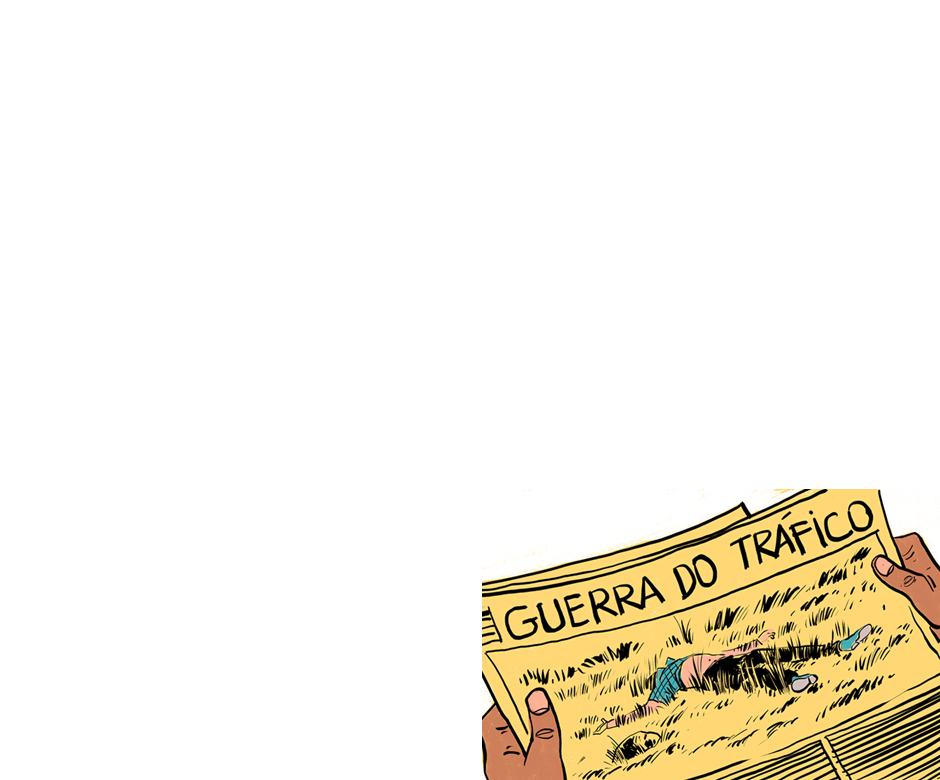

The astronomic profits to be made from the drug trade led to the emergence of rival factions such as the Terceiro Comando (“Third Command”) and Amigos dos Amigos (“Friends of Friends”).

Wars broke out, and there was much bloodshed.

Drug trafficking dominated the favelas, but removals seemed to have halted. The process of favela urbanization began to be consolidated.

Before

In 1995, the program Favela-Bairro appeared, during the government of César Maia. It received large foreign investment.

After

Since 2000, however, the policy of removals has returned, under the pretext of major sporting events held in Rio.

In 2009, to contain the favela expansion, the government announced the construction of walls in 11 communities in South Rio. The measure provoked much criticism, such as this from Rossino de Castro, president of the Federation of Associations of Favela Residents of the State of Rio.

We are against this.

We don’t need walls.

What we need are public policies –not the transformation of the favela into a ghetto.

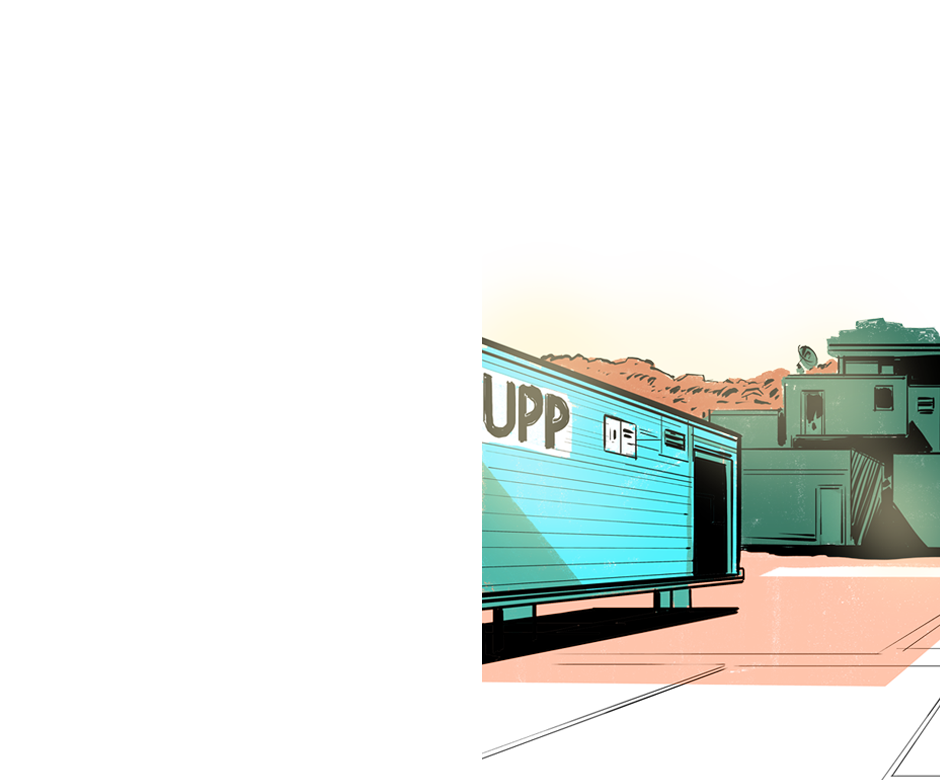

A year before, in 2008, the favelas had seen the implementation of a new public security policy: the UPPs.

…and the pursuit of the suspects continues with the help of the army…

These guys have had it…

There will be no-one left to tell the story.

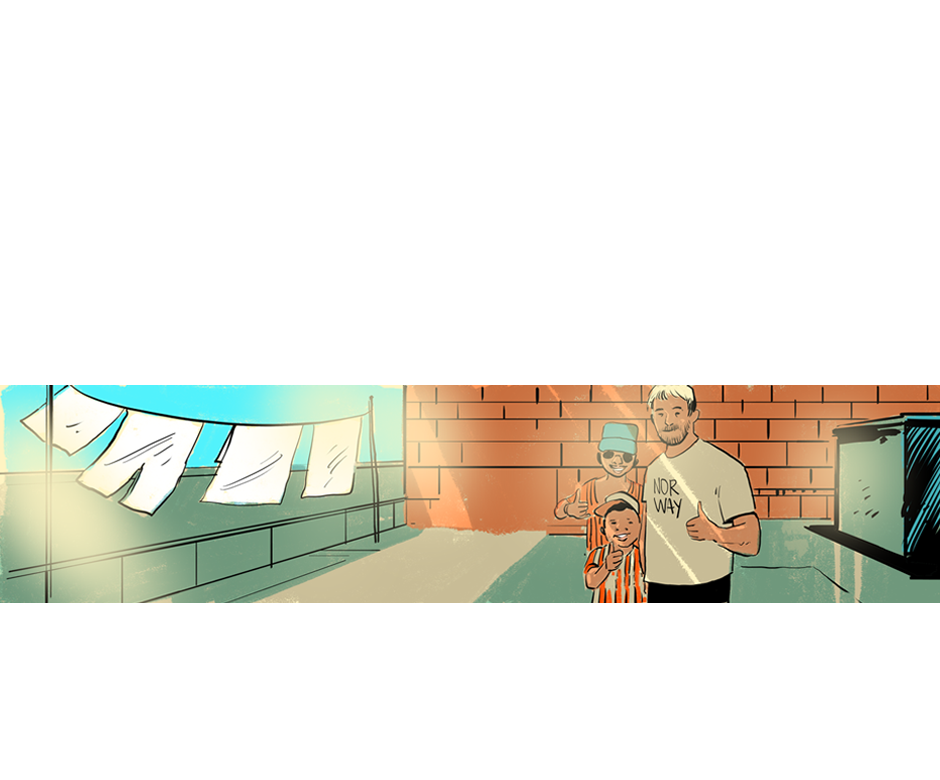

A project that has produced the expulsion –even if only temporary– of the drug trade.

…and the rediscovery of the hills by the city’s other residents and tourists.

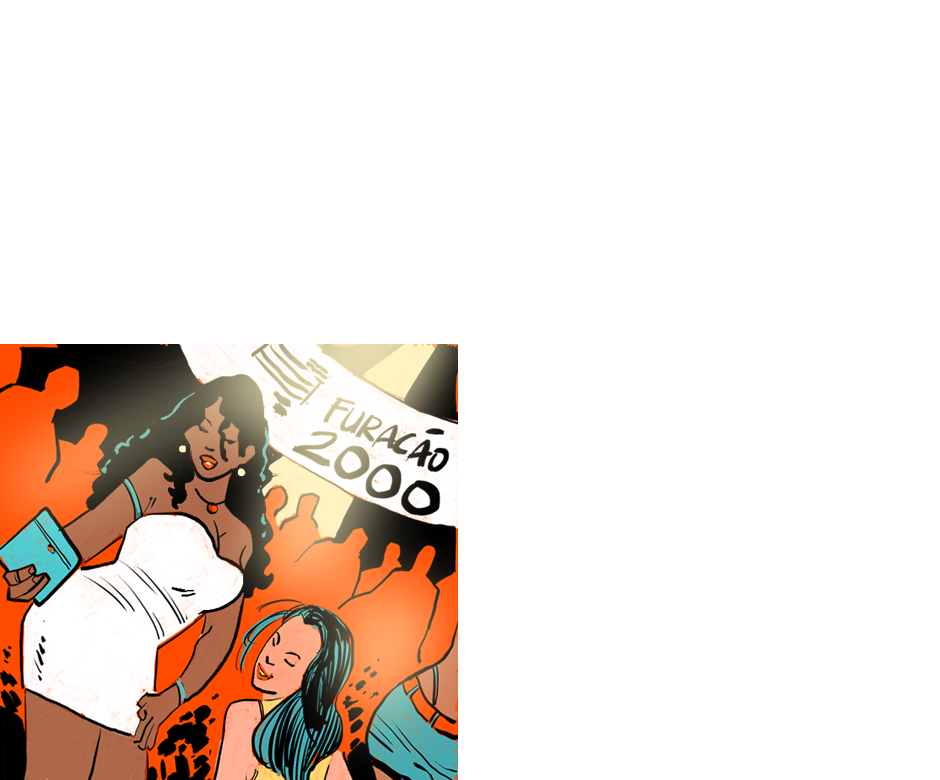

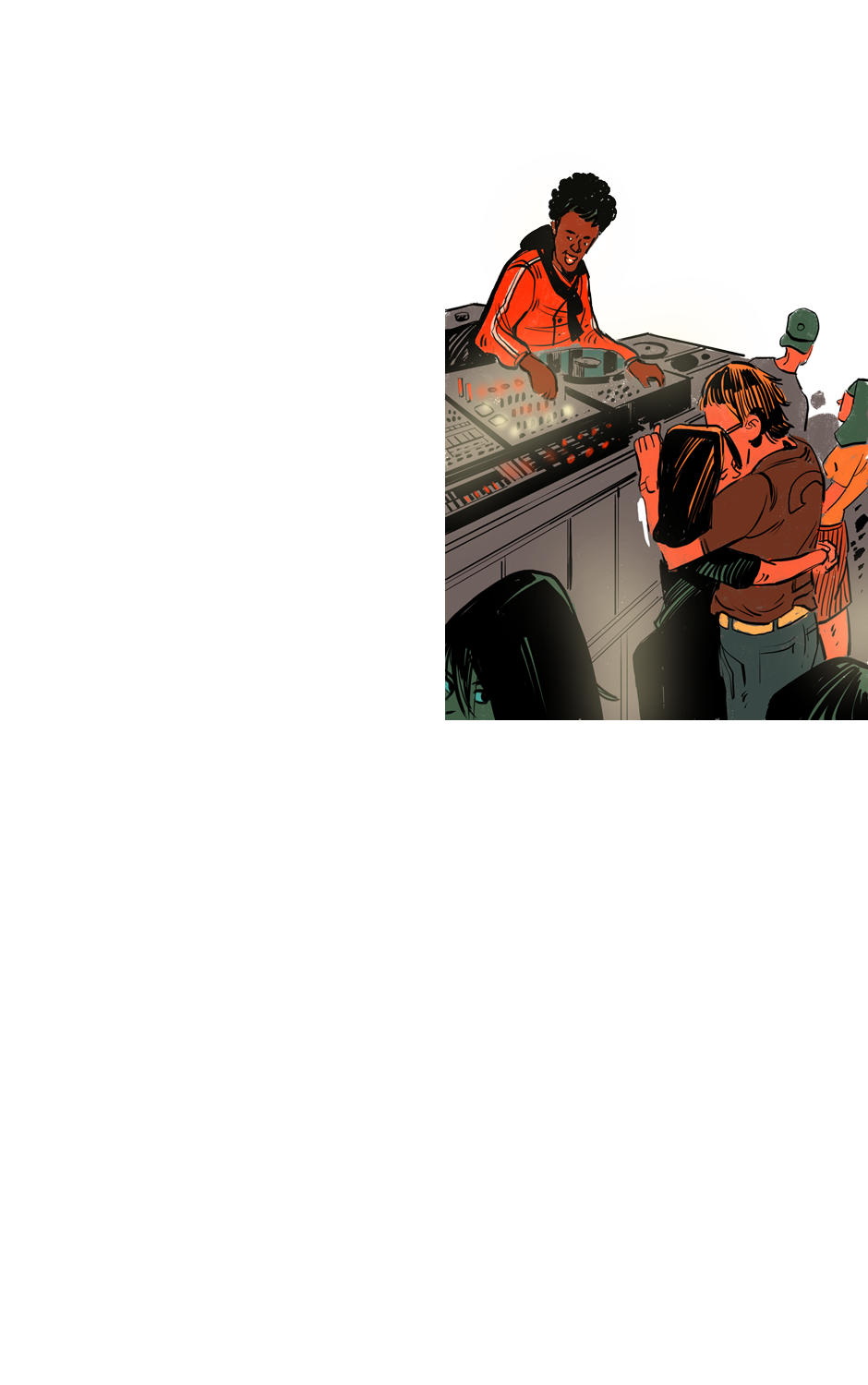

From the 1990s, the funk parties became one of the main cultural expressions of the favelas, bringing together local residents and people from elsewhere in the city.

Since the introduction of the UPPS, they have become less common, as they now require authorization from local police commanders, which is almost always denied.

The favela became fashionable.

Some favelas now have cable cars, hostels and parties that bring together local residents and tourists.

Spots such as the Arvrão lookout point, in Vidigal, are popular thanks to their spectacular views.

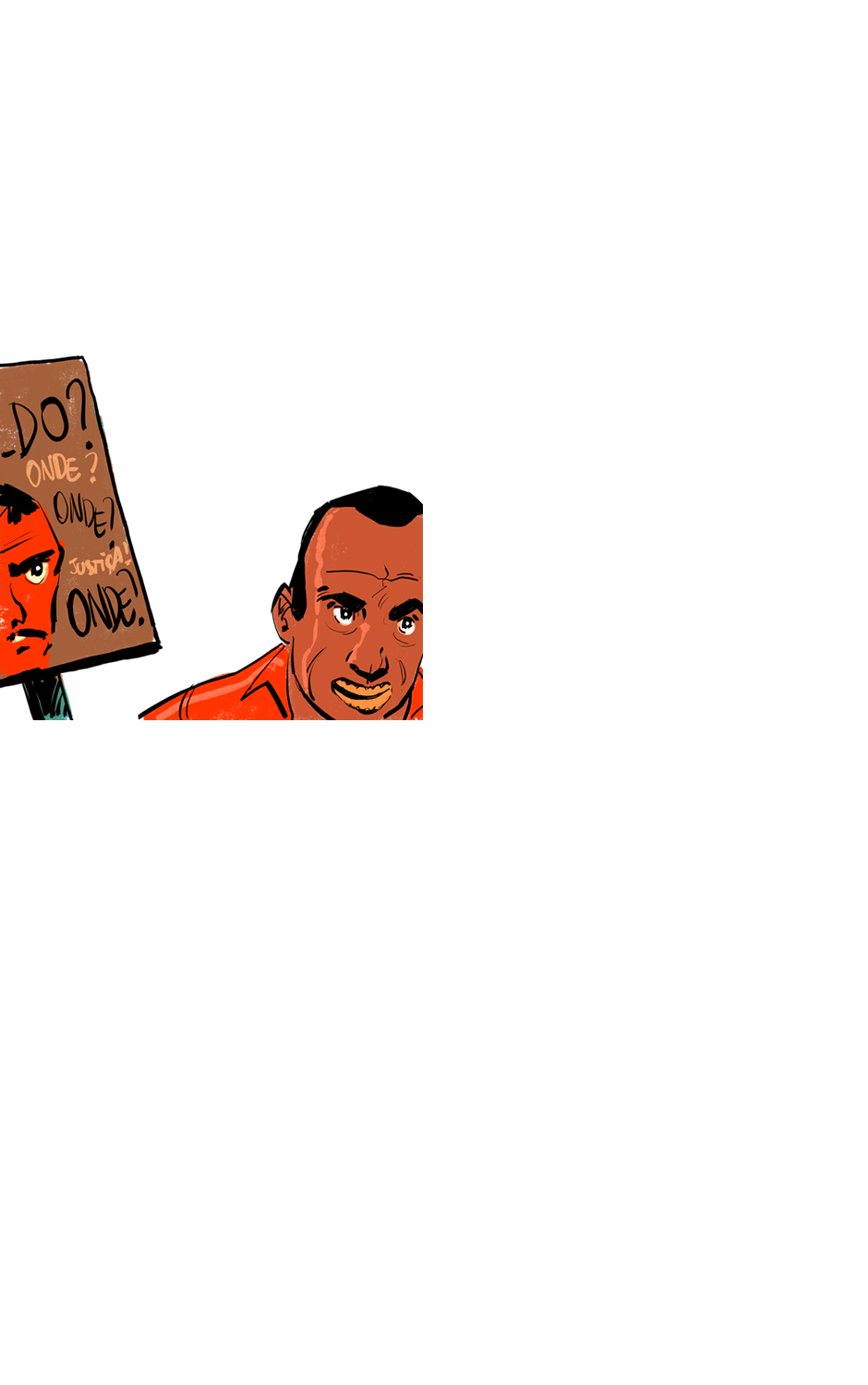

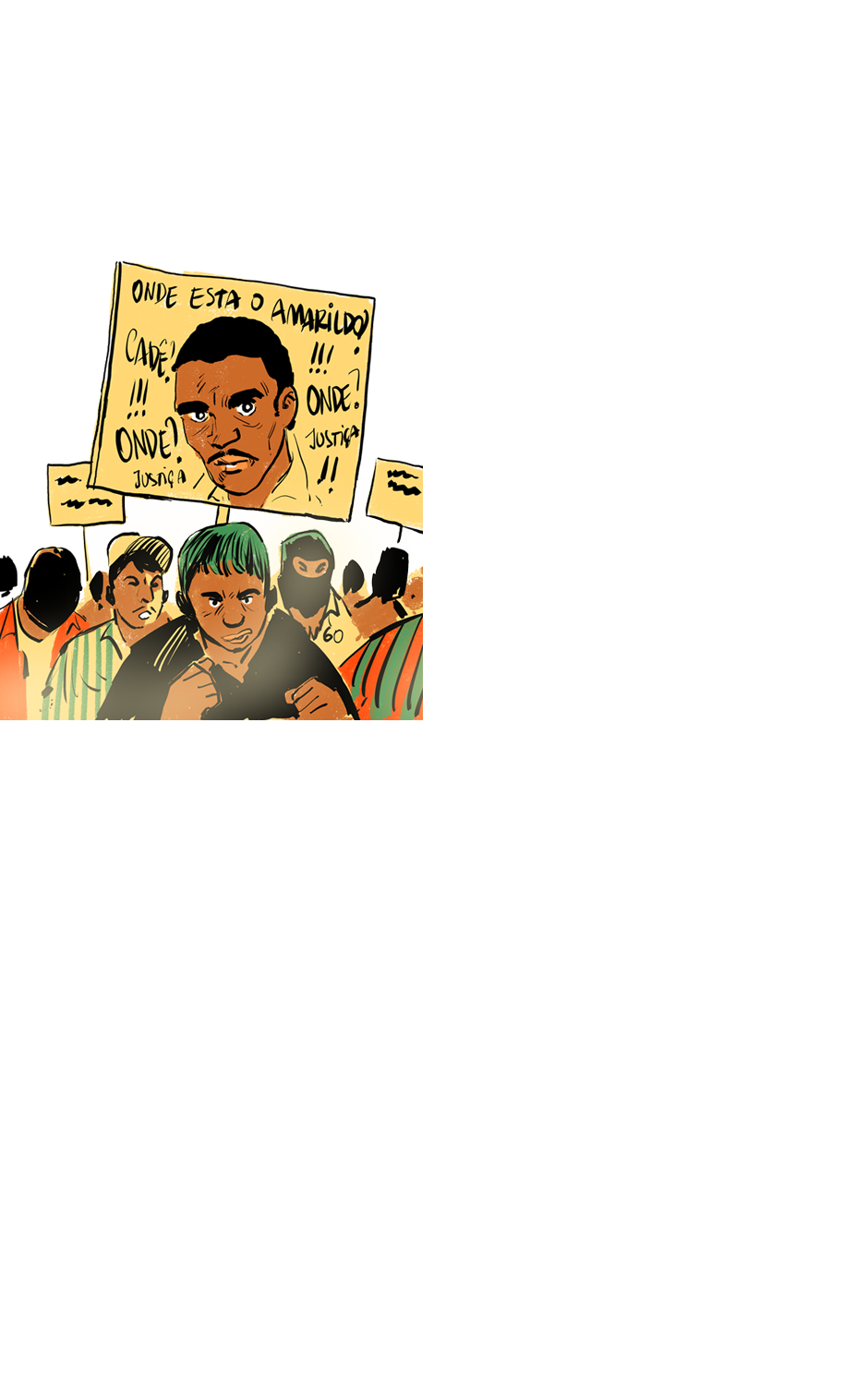

However, the reality of favela residents is no party. In July 2013, in Rocinha, Rio’s largest favela with nearly 70,000 residents, the laborer Amarildo de Souza disappeared, provoking a series of popular protests. According to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, he was tortured and killed by UPP officers.

The case, which was widely publicized, showed the potential for mobilization by favela residents through a variety of means: legal action, residents’ associations, universities and the press.

We are in the era of favela.com, where any type of abuse or police brutality is denounced in blogs, on social networks and via applications such as WhatsApp.

“With more than a century of history, nearly 1.5 million residents, the birthplace of some of the most iconic cultural creations of Rio, like samba,

the samba school, the Carnival parade, capoeira, the pagode of Fundo de Quintal,

club pagode and the funk parties,

…the favelas have shown that they are about a lot more than just segregated areas.”*

*Alba Zaluar, in the book Um Século de Favela (“A Century of the Favela”)