Excluded

Along the Edge of the Highway, Poverty Is Hidden While Crime Prospers

24.jul.2017 - 02h00

{{video=4}}

Two times per week, dentist Mariana Salgado, 39, passes by car in front of the concrete wall that was constructed at kilometer 58.5 of the Immigrants Highway in Cubatão (São Paulo).

As she is getting close, she gets nervous, wondering if someone will show up out of nowhere with a gun in their hand. "I have no idea what is behind that wall", says the dentist, who lives in Santos and sees patients in São Paulo on Tuesdays and Thursdays. "I just know that two of my friends were robbed there."

{{info=3}}

{{imagem=12}}

Like Mariana, hundreds of thousands of middle-class São Paulo residents travel down to the coast by the Immigrants highway, paying the R$25.60 (US$ 8.20) toll, while having no idea of what exists behind this 3 meter-high, 25 centimeter-thick, 1 kilometer-long extension, which was built by the Ecovias company in May of 2016.

The wall separates tourists from the approximately 25,000 inhabitants of Vila Esperança, a favela (slum) where 12% of the population has no income at all, 14% make up to one minimum salary, and everyone empties their sewage in the river that flows out to the beaches visited by middle-class São Paulo residents.

Along this one-kilometer stretch alone, there were seven robberies in 2015, one robbery and one robbery resulting in death in 2016 and another robbery and attempted robbery in 2017, according to the highway police.

According to Ecovias, the company build the wall to "improve public safety conditions in the highway".

{{imagem=1}}

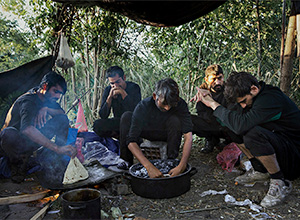

Enhanced illumination was also installed along the stretch, as well as new security cameras for police monitoring. The favela is controlled by drug traffickers.

The wall took Vila Esperança's residents by surprise. Construction started one day from out of nowhere, nobody was notified in advance.

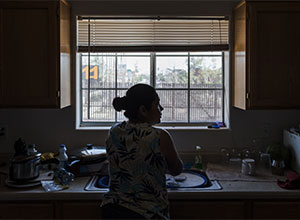

"This wall here, it's for protecting the tourists, right? But what about us folks? We have to pass right by it to sell things on the highway", says Luzia Gonçalves da Silva, 54, from Rio Grande do Norte. For her, the barrier just messed everything up.

Luzia used to sell water, soda, manioc puffs, and bacon-flavored snacks in the highway. She could see the highway from her window, and when it would back up with traffic, she would celebrate.

She would then fill up her styrofoam cool-case with refreshments and load it on her handcart. Once, on New Year's Eve, she even spent the whole night selling.

{{mosaico=2}}

{{info=1}}

But Luiza had to quit working as a street vendor. Because of the wall, the path to the highway got longer, and she wasn't able to pull the heavy handcart through the mud. At any rate, it ended up not mattering, because if she managed to get there the security guard would send her back, anyway.

So she opened up a bar, the Bar da Sofrência (Bar of Suffering) below the overpass in the neighborhood where she sells shots of firewater for R$ 2 (US$ 0.65) and brandy for R$ 2.50 (US$ 0.80). "But business is slow. Who is going to buy anything if nobody has a job and the drunks only want to buy on credit?".

Luzia migrated from the State of Rio Grande do Norte to the city of Cubatão when she was 13 years old, at the height of the "economic miracle" during the military dictatorship. At that time, there were many industries located in the municipality. She went to work at a fair in the Vila Parisi neighborhood, a low-income area that became known afterwards as the heart of the Vale da Morte (Valley of Death) after 37 babies were born without brains, due to the high concentration of pollutants.

{{video=3}}

Sebastião Ribeiro, known as "Zombi", christened the concrete barrier constructed by Ecovias the 'Wall of Shame'. "When they don't know what else to do, they build a wall and think that they have taken care of the problem", he says.

"There are more than 20,000 residents here paying for what just a few did".

Vila Esperança traces its roots back to 1972, to the beginning of the construction of the Immigrants highway. Some of the construction workers working on the project built their shacks and stilt-houses in the mangrove, which is an environmentally protected area.

'Zombi' came from the state of Maranhão in 1980 and settled in a shack with his mother and six brothers and sisters. During the 1990s, with the economic crisis at the time, the population of the favela skyrocketed because many people in the industrial pole lost their jobs and ended up as a consequence invading of the area.

The Maranhão migrant, who today is 47 years old, grew up selling bottled water and baked coconut sweets on the Immigrant highway with his mother. He completed a Law Degree at 44 and today is the Vila Esperança's principal community leader, in addition to the Social Welfare Secretary of Cubatão.

{{mosaico=1}}

He founded an NGO which exchanges recycled materials for a currency called "Mangrove" which can be used at the entity's small store or in other local establishments.

According to Zombi, the community also has its own wall of pride, which was built by the company ALL Logística (currently named Rumo) to separate the favela from the railway, in order to prevent accidents.

When the railway was duplicated, Rumo promised to execute some compensatory projects in order to secure the environmental license. They paved the main thoroughfare, built pedestrian bridges, refurbished the NGO facilities, and equipped the computer laboratory with 18 new computers.

Additionally, a 3.5 kilometer wall is being gradually decorated with graffiti art by residents of the Vila Esperança, who are learning graffiti art with artist Tuim, from a nearby favela.

{{video=1}}

{{imagem=13}} [[[[infográfico: fluxo sist. imigrantes/anchieta]]]

"Any major construction project creates difficulties for the population, and because of this we reached out to the community to identify existing mini-projects to mitigate the impacts of the railway duplication", says Silva Mari Azuma, Rumo's environmental licensing coordinator.

Ecovias says that its responsibilities are limited to the extension, conservation, maintenance and operation of highways. "Community related subjects are the responsibility of the public authorities", declares the company.

In fact, according to ARTESP, the State's transportation regulatory agency, construction of the wall does not require an environmental license, therefore there are no mandatory compensatory measures.

This doesn't satisfy the critics. "In the clear 21st century, they built an apartheid wall to isolate the poor", says Ademário Oliveira, the mayor of Cubatão.

"They should have invested that money in housing, water and sanitation in the community." Ecovias spent R$ 14.4 million (US$ 4.6 million) on the wall and related security infrastructure.

{{imagem=7}}

{{info=2}}

For the vast majority of the population who have no hope of ever leaving the Vila Esperança, the wall makes no difference.

"I don't have anything to say about that wall there, for me it doesn't matter whatever they did", says 23-year-old Carlos Alexandre Vieira de Lima, known as "Xambito".

At 3 PM on a Monday afternoon, the small soccer field under the Vila Esperança overpass is full of barefoot young people watching a classic matchup of teams Dois Poste against Santa Cruz.

Nobody has a job. Xambito is one of them.

{{mosaico=3}}

"I used to have daily work as a mason, R$ 60 [US$ 20] and food, and at the fair it was R$50 [US$ 16] on Saturday, R$50 on Sunday, and I would get some vegetables. Today there is nothing".

Xambito's mother is a crack addict. She served three years in prison after trying to kill her alcoholic husband by putting rat poison in his coffee. Xambito's sister is also a crack addict and a works as a prostitute.

His father killed a man, is incarcerated, and hasn't seen Xambito for more than 15 years.

"My mother has never worked; crack, firewater and cocaine destroyed her life. When I talk to her I don't shed a tear anymore, I've surrendered to the hand of God", he says. "If you could see her, my mother's skin is half white, half black, something happened, she is really ugly, crack destroys a person".

{{imagem=10}}

Xambito needs to pay child support for his three-year-old son, but he doesn't want to go back to the "wrong life", as he says.

"I was about 16 when I got into that crazy life. When folks managed to get a job, they got out, but when we are in need of money, we go back to that wrong life", he explains.

"This wrong life here, biqueira [drug sale point], drug trafficking, it only goes one of two ways: prison or death; I don't want either of these, I want to see my son grow up, to play soccer, to go to school", says Xambito, who walks around the favela with a boom box playing country music by Felipe Araújo.

He is looking for "booked job" (formally registered). He has already gone several times to the factory patios in Cubatão, but says that 500 people show up for 10 positions. "I'll only be called with God's help, there's lots of unemployed folks".

{{video=2}}

In the Vila, only 24% of residents have a high school diploma. Xambito dropped out in his fifth year and has already tried to go back to school many times. "I need to be strong, persistent, you know, because after two or three months it gets tiring; I start smoking pot, get lard-assed, and end up going back home".

Smoking pot, playing soccer and piggy-backing on the Wi-Fi connection from the neighbor's shack to get on WhatsApp and Facebook –this is the day-by-day for Xambito and the majority of his friends in the Vila Esperança. "I want to change my life, but it's really damn hard."

He has already tried religion. "I spent two, three months going to church, worshiped tremendously, but we're weak, you know, I stopped going and ended up back in the wrong life."

{{info=4}}

{{imagem=11}}

On the poor side of the wall, opportunity is a rare thing.

"Folks wake up and think, damn, and now, how am I going to get some money together, by stealing? What am I going to do? I thought about this, stealing, I can't say that I didn't think about it. But I know that, if I do this, I might or might not come back home."

Xambito says that he doesn't want to give in to the wrong life. But the temptation is strong. "In the wrong life, folks end up with good money, man."

On May the 27th, 2016, Reinaldo Lima de Souza, a 17-year-old student, died at kilometer 79 on the Immigrants highway. During an attempted robbery, Reinando was hit in the face by a rock that broke through the window of the car he was travelling in.

The three-meter-high wall built by Ecovias was already in place, isolating the Vila Esperança community.