Shack used by crack and heroin addicts in the Picheleira neighborhood in Lisbon - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

The police caught Igor, 16, smoking hashish on a Sunday afternoon, on March 1st. Had he been in Cyprus or Sweden, the young man would have gone to jail. But he was in Portugal, and his destination was different: he was ordered to show up at 10:30 the next morning to an unmarked room, on the first floor of a standard commercial building in Lisbon.

The Commission for the Deterrence of Drug Addiction (CDT) is located there, and this is the home of the drug policy considered one of the most successful in the world and the most original in Europe.

Igor was arrested because using drugs in Portugal is a misdemeanor, but not a crime. Nor is it a crime to take the equivalent of up to ten doses of drugs (25 grams of marijuana, 5 g of hashish, 2 g of cocaine or 1 g of heroin or amphetamines, according to the criteria of the World Health Organization).

In the 35 minutes he spent at the CDT, a psychologist tried to understand whether Igor has a substance use disorder and whether he is at risk. This diagnosis guides the treatment. A night watchman who can’t sleep without taking drugs once a day is different from a young man caught on the street at 9 AM because his math teacher is very boring, says Nuno Capaz, 43, vice president of CDT.

The approximately 3,000 people who pass through the Lisbon screening agency each year can leave simply with a fine, an order to go to activity centers, training programs or job centers, or with a referral for medical treatment.

The originality of Portugal’s plan, however, was not decriminalizing the use of drugs, which occurs in five other European countries. It has taken drug use out of the judicial sphere and placed it under the responsibility of health, says Brendan Hughes, the principal drug law scientist at the European Union Center for Drug and Dependency Monitoring (EMCDDA).

“From a medical point of view, if the addict starts retaking drugs, you go back to treating him as many times as necessary. In court, with each new ‘mistake,’ you increase the penalty,” he says.

The strategy means Portugal has essentially given up on the idea of a drug-free society, says Capaz: “No health system has the goal of ending disease. As a doctor who accepts a diabetic patient who eats a slice of chocolate cake, I can live with the idea of someone who, despite all the information, decides to stay on drugs. A judge cannot do it.”

Not only did Portugal’s system change the traditional perspective on drug abuse, but it also combined drug issues under a single umbrella to ensure administrative agility and political shielding, according to Manuel Cardoso, 64, deputy director-general of Service for Intervention in Additive Behaviors and Dependencies.

According to the public health specialist, who has worked in the area since 1995, the strategy arose after a heroin epidemic hit “all Portuguese families”. “Overdose deaths were one per day in the late 1990s, and all classes named drugs as the country’s main problem,” says Cardoso.

Heroin addicts numbered 100,000 (1% of the population), half injected, spreading HIV and hepatitis C viruses. The alarm was so great that the government created a team of psychiatrists, psychologists, epidemiologists, general practitioners, nurses, and lawyers to formulate a national plan.

The report suggested decriminalizing the use of all drugs, an idea that snowballed into a bill, approved by the Assembly in 2000, and put into effect in 2001. According to Cardoso, the basic principles were two: the dependent has the same right as others. If consumption cannot be stopped, harm must be reduced to the dependent, his/her family, and the community.

View of Casal Ventoso, a neighborhood in Lisbon that was the largest open-air drug market in Europe in the 1990s - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

A branch of a social assistance and treatment center operates at the same location that became known as the largest open-air drug market in the world, Casal Ventoso, west of Lisbon.

Thousands of shacks with more than 50 points of sale operated 24 hours a day. They were torn down at the turn of the century, and then the area was surrounded. There’s a highway that cuts an open space and a white van with no logos or signs parks there every day.

On the afternoon of March 3, a taxi parked at the back of the road, and its occupant went to the van, exchanged a few words with the employee through the small window, received a plastic cup, drank the contents, and said goodbye. As he returned to the road, a BMW pulled over, and his driver repeated the ritual.

Patient takes methadone distributed by the Ares de Pinhal institution in Lisbon - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

Every day, about 1,200 people seek the banana-flavored bitter liquid in the vans of the NGO Ares do Pinhal. It is methadone, a substance that appeases the need for heroin without altering psychic functions, which gives dependents the possibility of a normal life, says psychologist Hugo Faria, 47.

This is the case for the eight taxi drivers that Folha saw parked during the six hours in which the publication observed the van in two different places. This is also the case for Emanuel, 44, who every day bikes 20 minutes to take his dose before going to work at a cleaning firm. A heroin user since he was 16, he joined the methadone program six years ago “after seeing the degradation of everyone around me.” He says that he has never missed a day of work or failed to pay a bill since then.

Methadone distribution van in the Casal Ventoso neighborhood in Lisbon - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

Ares do Pinhal’s methadone program is low threshold because it demands little from users. One needs to prove heroin use (with a five-minute urine test) and commit to taking doses every day.

The organization also directs people to documentation, treatment, and housing services, gives medical consultations and tests for tuberculosis and other infections.

According to Faria, the goal is not for people to give up drugs, but for narcotics to stop being harmful to addicts and others around them. More than half of those who attend the program achieve this goal, he says.

Those who stabilize can go to treatment centers, where there are psychotherapeutic consultations, and it is possible to take home enough methadone for ten days. However, in this case, as in the treatment communities, the threshold is higher: complete abstinence is required.

According to Cardoso of Sicad, the rate of heroin users who inject the drug has plummeted from 48% to 3%. The percent of those who inject and who were infected with HIV fell from 56% to 2% since methadone began to be distributed in Portugal 15 years ago.

But cocaine, for which there is no substitute, still worries the administration. For injectable drugs, in addition to the distribution of syringes and needles, harm reduction includes assisted consumption sites, where the user receives material and can use the drug under hygienic conditions.

Former user Vitor Manoel Pereira Correia, 60, works today as a peer educator in the mobile-assisted consumption of the GAT (group of treatment activists, created to prevent HIV contagion), a service supported by the Lisbon Chamber. It is a fundamental function when the target audience has a severe dependency and is not integrated into society. “We have the right experience and language, facilitate conversation and gain confidence,” says Correia.

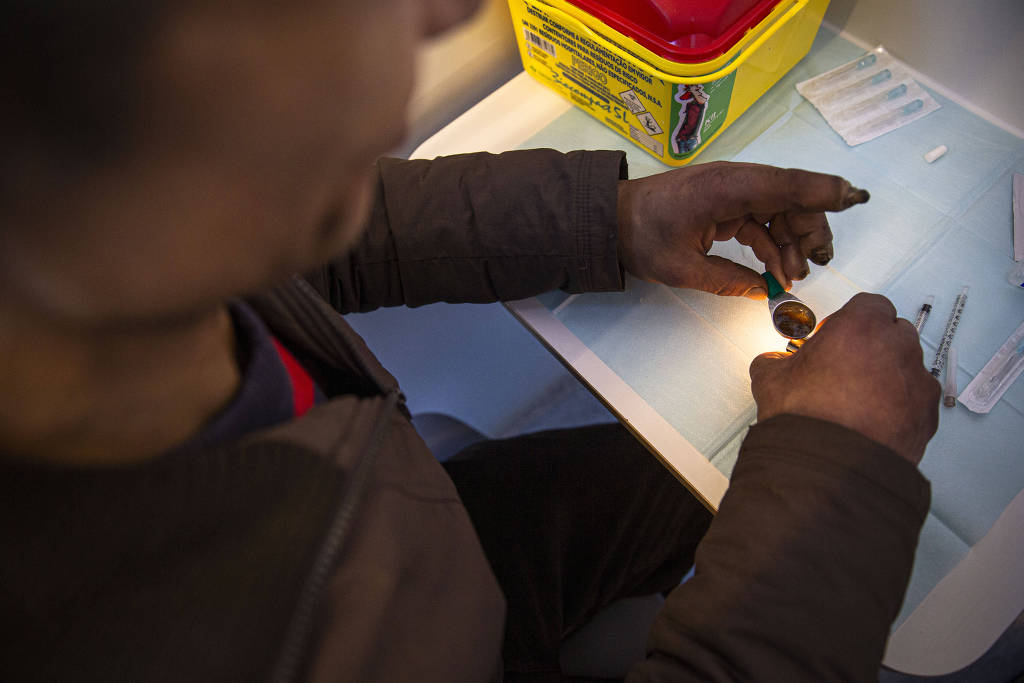

User prepares heroin in assisted consumer van in Lisbon - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

Assisted consumption rooms first appeared in Switzerland in the 1980s and expanded to Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Norway, Denmark, Greece, and France. In Portugal, they have been allowed by law since 2001. But they only started operating 18 years later as mobile units.

Social worker Diana Gautier says that before opening the service in Morro do Beato, meetings were held with residents to explain that there would be no incentive to consume. “We only accept those who are already dependent. Also, those who use them here do not leave syringes on the street, are not in sight of children, and receive social, medical, and psychological support.”

When dependents do not come to harm reduction services, services go to them. While a doctor and nurse receive users in the mobile room, the peer educator fills up a backpack with syringe kits and condoms.

The Associação Crescer team looks for users to distribute disposable materials and collects syringes in the Picheleira neighborhood in Lisbon - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

The same goes for the Crescer Foundation’s street teams, where nurse Inês and peer educator Martim work. In the afternoons from Monday to Friday, they make a circuit through Picheleira, at the foot of Morro do Beato, the parish of Areeiro and Largo do Intendente, in the city center.

Martim, 41, injected cocaine and heroin for 25 years. He stopped three years ago, he says, as he enters carrying kits and a plastic bucket to collect syringes. Its public is 80% unemployed and homeless people who live in extreme poverty.

Zé and Aida emerge from a shack made of boards, cardboard, and plastic to get kits of syringes and “silverware” (aluminum foils in which they heat the drug to smoke it). The woman, who looks 50 years old, asks for help from the nurse to treat her leg, where the injections have left a hole as wide as a finger. “But first I need to smoke,” she says, distressed.

Inês bandages Aida, gives her a glass of hydrogen peroxide, and suggests that she make an appointment with a doctor. “I’ve been infected in my head and everything,” replies the user, covering the dressing with nylon pants stained with pus and blood.

Crack and heroin users in the Casal Ventoso neighborhood in Lisbon - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

At the next stop, the Crescer duo meets Toninho, 40, under a subway line. He has been using for 17 years and says he didn’t like methadone. He lost his job in civil construction three months ago and is waiting for a spot in the therapeutic community. But he complains: “The wait is enough for one to despair. They should help us when we are most willing.”

Some have been waiting for eight months, says the Crescer duo, showing one of the main gaps in Portuguese politics: treatment. What is lacking is not service capacity at the contracted entities, but funds to guarantee stays.

Therapeutic communities were the lifeline of computer engineer Jorge, 55, a former manager of a large company from which he hoped to retire until he found himself without a job after the 2008 crisis.

“It was as if the rug was pulled from under my feet. I already had problems with alcohol, and everything got worse. My personal life went downhill,” he says. He managed a spot at Ares do Pinhal, where about 80 people undergo treatment each year.

Jorge, 55, at the Ares do Pinhal Therapeutic House in Sintra - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

There are other ways to rebuild a life, as Alexandra Prata, 40, shows. Prata is young, well cared for, and calm, and on a Thursday night, she matched her eyeshadow with the green of É Um Restaurante’s apron, where she works in a tourist region of Lisbon.

In partnership with Crescer, Nuno Bergonzi, star of the Portuguese version of the TV program Masterchef, runs the house and gives former users professional training and job guidance.

At 8 PM on March 5, before the coronavirus had spread to Portugal, the ten tables start to get busy, and Prata guides the work of the most inexperienced students. One of them is called to attend a table of foreigners –Zé speaks English, French, and Spanish.

Although there are still gaps, Portugal’s public health approach reduces one of the problems that most concern the EMCDDA: deaths from overdose, mainly from opioids.

This class of drugs, which includes heroin, can produce acute respiratory arrest, with no time for relief. Therefore, it causes 90% of overdose deaths, which have grown in recent years, according to the leading scientific consequences health analyst at EMCDDA, Isabelle Giraudon. There were 9,461 deaths in the 30 countries monitored by the center (the 27 in the EU, plus the United Kingdom, Norway, and Turkey) in 2017. In Portugal, there were less than 30.

The risk increases in less tolerant countries because of fear of seeking help, she says. The spread of synthetic opioids that are much more potent than heroin, such as fentanyl and the like, also caused spikes in overdoses in England, Estonia, and Sweden.

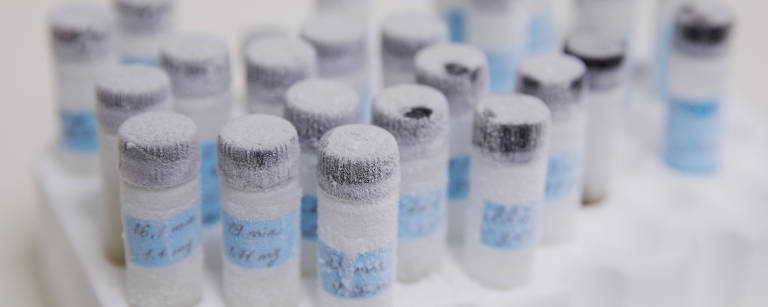

Until 2016, the most commonly used drugs in Europe were cannabinoids or MDMA-type stimulants (ecstasy). Still, diversification has grown, according to Rachel Christie, an analyst at the European Center for Narcotics Trends.

Much more potent synthetic versions appeared, such as carfentanil, a tranquilizer for elephants 80 times more potent than heroin (which allows trafficking in much smaller quantities, difficult to detect, but equivalent to tens of thousands of doses).

The main frontier of the current discussion is the regularization of the production and sale of drugs, as Uruguay, Canada, and the American states have done.

In the European Union, this step is hampered by the bloc’s commitment to respect the United Nations conventions on the subject. Scientists and politicians, however, note that the international drug convention dates back to 1961, inadequate for current reality and knowledge.

Although limited, scientific studies have come a long way, says Jan Ramaerkers, 56, a professor of neuropsychology who coordinates the drug research laboratory at the University of Maastrich in the Netherlands.

According to Ramaerkers, who advocates a change in laws based on each drug’s pharmacological qualities, “MDMA (ecstasy), for example, is not addictive, and psychedelic substances have opened an interesting avenue for therapeutic research.”

Graffiti in the Casal Ventoso neighborhood in Lisbon - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress