Employee extracts marijuana oil at the Bazelet company, near Tel Aviv - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

In order to enter Cannasure Therapeutics, one must step on a sticky doormat that looks like duct tape and then on a soaked one that “washes” the soles of shoes. Then one must put protectors on their feet, caps on their hair, and wear a mask, overalls, and gloves. This routine resembles the use of personal protective equipment by health professionals in the Covid-19 pandemic. Still, it is actually part of the pharmaceutical quality control protocol created in Israel for its growing medical marijuana industry.

Cannasure Therapeutics is a new venture by a leading industrial group in soybean oil extraction. It grows cannabis flowers from which it manufactures five types of oil for different applications and develops marijuana-based gynecological products.

In the 1960s, Israel pioneered the modern history of the therapeutic use of cannabis from scientific discoveries that revolutionized the understanding of marijuana and its effects when the plant was illegal across the world.

The country’s scientific vanguard and its tradition of innovation in intensive agriculture, and the “high tech” profile of the economy have made the country an exporter in research and development on medical marijuana.

Today, Israel is home to around 100 cannabis startups, partnerships between universities and industries, and programs that attract foreign capital to the sector. The sector underwent a medicalization process in 2016, in which the government framed medical marijuana within the parameters of conventional pharmaceuticals.

Analysis by consultancy Arcview, which specializes in cannabis, points out that the global medical marijuana trade grew more than 45% between 2018 and 2019, when it reached US $ 14.9 billion –a value that should almost triple in four years, according to the study.

Still, it is unusual to cover yourself from head to toe to access controlled environments where machines fill cigarettes with marijuana.

Part of this strangeness is due to decades of criminalization of marijuana, which attached the stigma of danger and marginality to Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica, and Cannabis ruderalis plants and their effects.

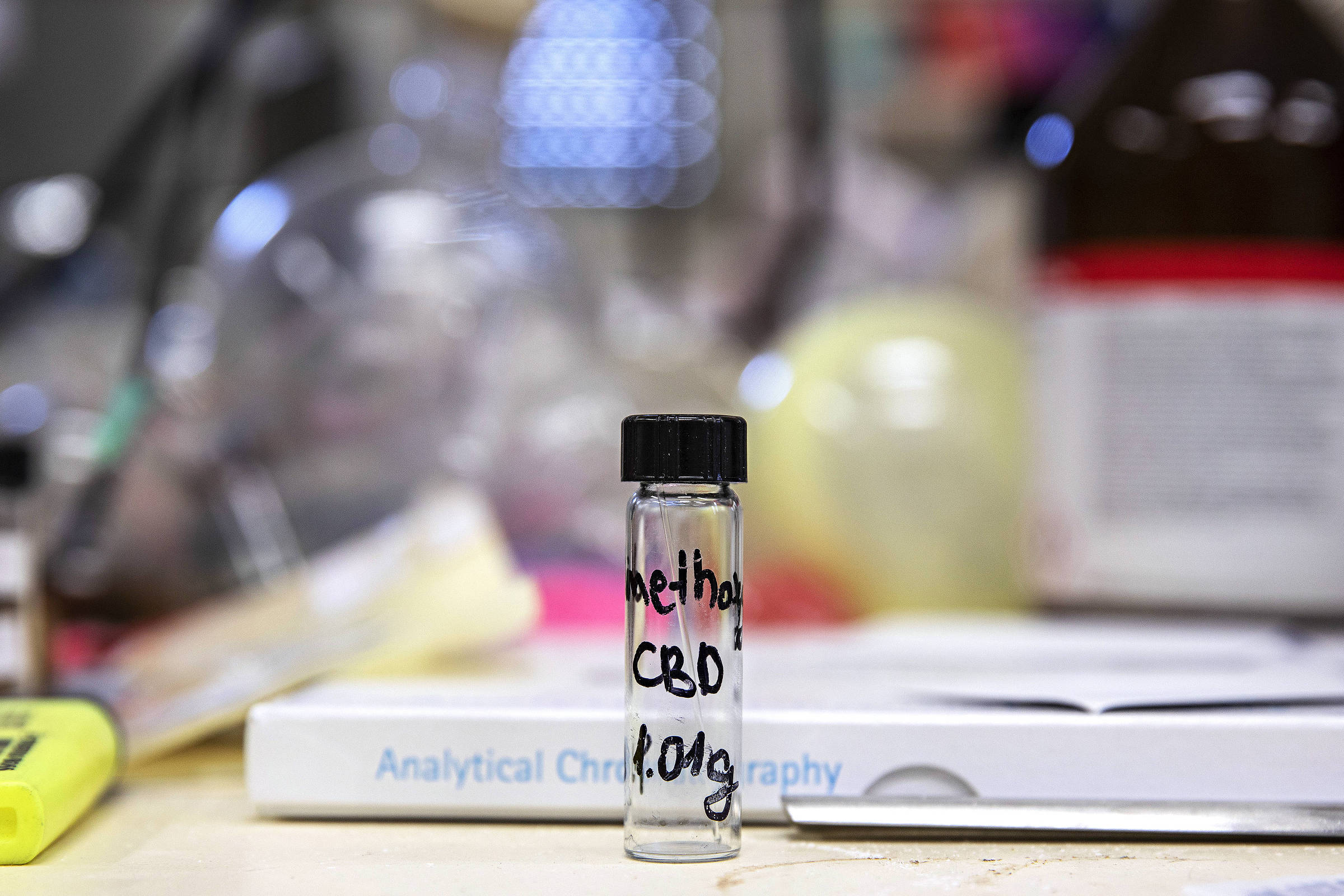

Another part of the strangeness dissipates during Folha’s visit to the other facilities of the Israeli factories. In them, cannabis flowers are selected, pruned, crushed, and dissolved to extract oils intended to produce tablets, drops, suppositories, creams, and inhalers containing active ingredients derived from the plant.

The cannabis medicalization model created by the Israeli government starting in 2016 imposed a detailed regulatory architecture on the cultivation and manufacture of the plant to produce high-quality products, partly intended for export –authorized by the government in 2019.

The government has simplified the bureaucracy for approval of studies and clinical tests, speeding them up, in addition to subsidizing part of the sector’s innovation projects, divided between solutions for cultivation and consumption. The policy put Israeli companies at the top of the pyramid of medical marijuana-related patent holders.

“For an Israeli company, the only option is to innovate,” says Ran Amir, president of Cannasure. “We don’t have space for extensive cultivation, and, if we did, it would be costly. So the industry has to gain market-based on quality and technology.”

Cannasure marijuana seedlings in Tel Aviv - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

The cornerstone of the new industry was laid there almost 50 years ago by Bulgarian chemist Raphael Mechoulam. He was curious about the properties and mechanisms of the plant that would become a symbol of the counterculture among young middle-class people across the world.

Unlike other psychoactive substances, such as heroin and cocaine, whose components had already been identified, marijuana was still unknown from a biochemical point of view, despite evidence of ancient therapeutic use.

Internationally banned since 1937 and responsible for most arrests for violations of national drug laws to date, marijuana was a source of fear and misinformation. Mechoulam used a colleague’s contacts with the police to obtain the raw material for his research.

Only after taking a bus with 5 kg of hashish (cannabis resin) in the backpack, between the police station and his laboratory, did the scientist realize that something was wrong.

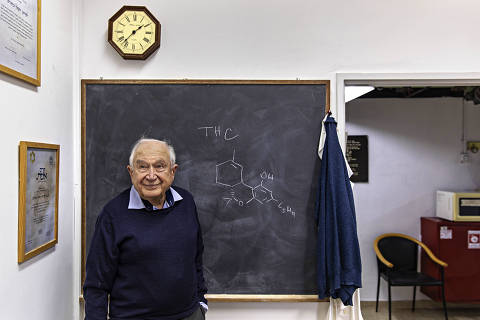

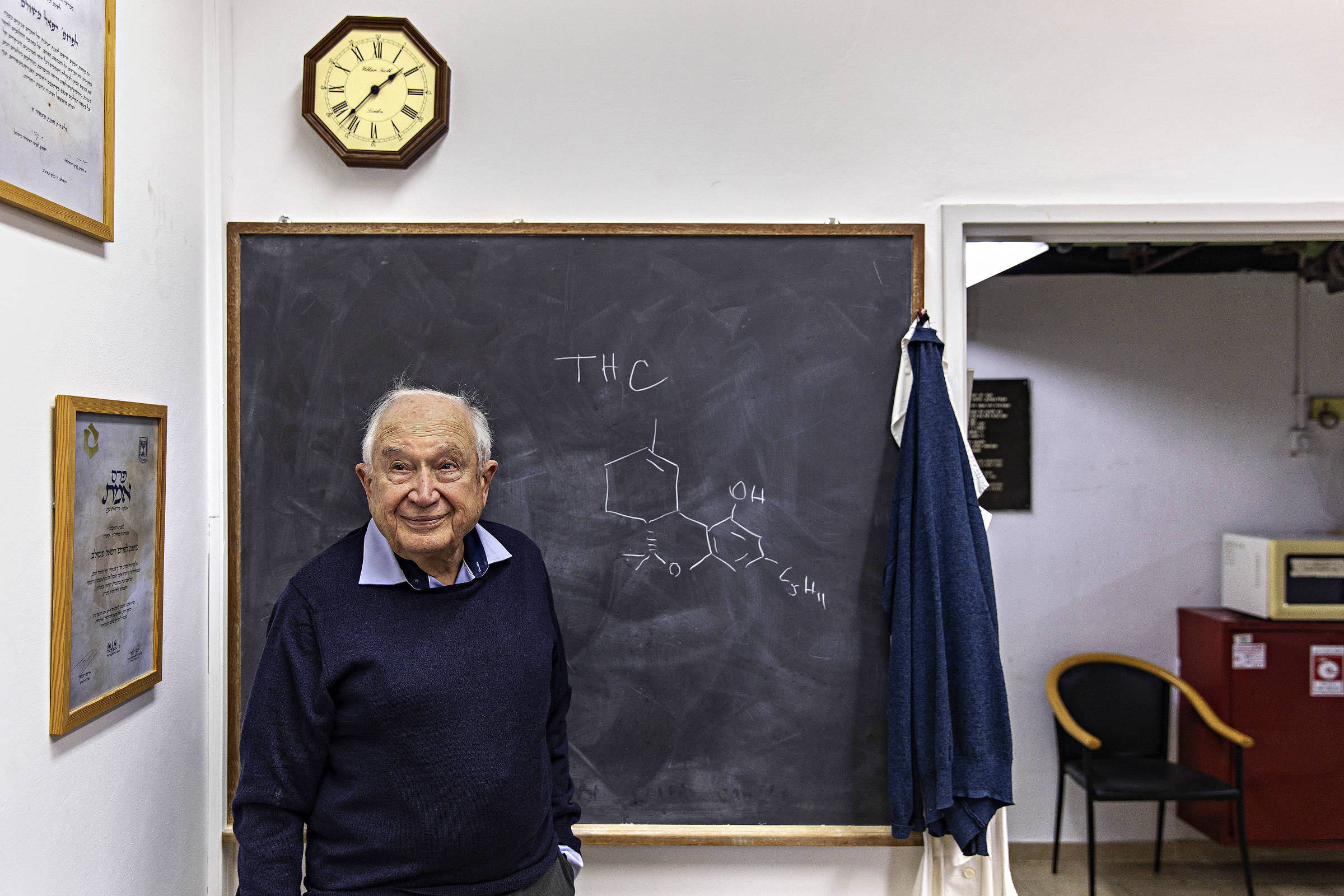

“Strictly speaking, I broke the law, and so did the police, because we needed the Ministry of Health’s approval to do that,” recalls Mechoulam, a short, good-humored man who, at the age of 89, walks happily through the building from the faculty of chemistry at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where he has been teaching since 1966.

“I was lucky because the Ministry of Health, after being consulted, thought that everything was fine. In this branch of scientific research, it is always good to have governments that are not too restrictive, and that know when to say yes and when to say no to doing research with the police outside your laboratory,” he says, in his office next to the laboratory, surrounded by books on marijuana and organic chemistry.

Above, Israeli chemist Raphael Mechoulam, who isolated THC in his office at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; chemist Lumir Hanus at Lumir Lab, Israeli medical cannabis start-up - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

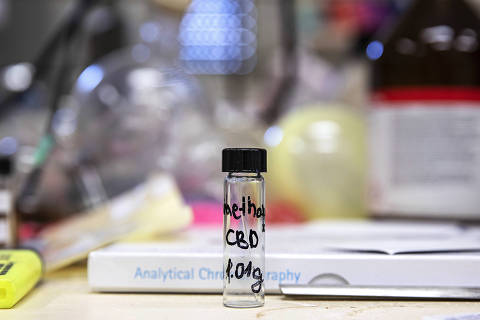

Between 1963 and 1964, Mechoulam identified the molecules of cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), two of the main active components of the plant, also known as cannabinoids. Today, most drugs derived from marijuana are based on these two components.

“Cannabis was seen as a damned drug, and nobody studied it,” says Mechoulam, who had his first request for scientific funding denied by the United States National Health Agency. “They said they saw no point in researching something that was used only in Mexico. And I argued that a lot of people in the United States used cannabis.” The agency would later reverse its decision and spend 45 years sponsoring Mechoulam’s marijuana research.

He cites the study done in partnership with the Brazilian physician Elisaldo Carlini, from the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp), published in the 1980s, which pointed out a consistent improvement in patients with epilepsy treated with CBD. “In the article, we suggested that the finding be turned into a drug, a process that requires clinical tests that are too expensive for academics like us,” explains the chemist.

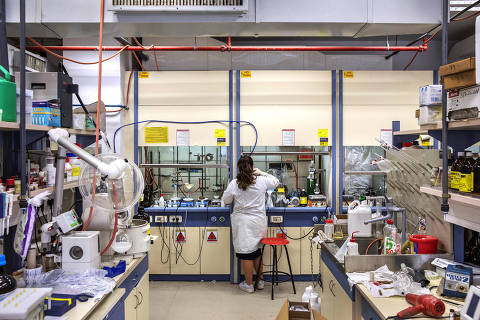

Researcher works in Raphael Mechoulam’s laboratory, at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

“I’m sorry to report that absolutely nothing has happened over 35 years,” he laments. The change came from the movement of parents of children with severe epilepsy in the USA, who had discovered the study, obtained CBD and found its benefits.

Their pressure prompted government authorization for clinical trials, which led to the approval of a marijuana-based drug.

“This could have been done 35 years ago, saving the lives of many children from the ruin of living with severe and constant crises. But nothing happened because governments and industry did not have an open mind. A pity.”

Today, just over 30 countries have made the therapeutic use of cannabis legal. Still, only a few, like Canada and Israel, have regulated cultivation for medicinal purposes, the manufacture of medicines, and research, which also occurs in parts of the United States.

“The challenge of cannabis for the industry is due to its reversed trajectory to that of other drugs, which emerge from the establishment for patients, and not from pressure from patients against the establishment,” says Tamir Gedo, president of Breath of Life Pharma (BOL), Israel’s largest integrated cultivation and production of marijuana-derived drugs.

Greenhouses used for cannabis cultivation at Breath of Life Pharma, near Tel Aviv - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

The executive has made a career at pharmaceutical company Teva, a maker of part of the iconic opioids of the US addiction and overdoses epidemic, and says the reverse engineering of marijuana incursion into large-scale production lines is unprecedented in the industry’s history.

“This same pressure from patients has affected several countries. The problem is that cannabis is treated as an illegal drug at the same time that it is a consolidated fact in some markets,” says Gedo, who manages 2,000 employees, 50,000 marijuana trees, and a 6,000 m² factory in a kibbutz near Tel Aviv.

For him, governments have neglected the issue “until they can no longer. And now they need to find new solutions that surpass common sense in relation to cannabis.”

In the 1990s, patients who felt benefits from cannabis use filed lawsuits against the Israeli government for the right to therapeutic use and were allowed to collect portions of marijuana directly with the police, as Mechoulam did for his pioneering research.

Hagit Yagoda, 57, was a patient who made the periodic pilgrimage to the police station. Diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma while in the Army, she underwent conventional treatments before receiving experimental therapy at the country’s largest hospital, the Sheba Medical Center in Tel Aviv.

Medical marijuana user Hagit Yagoda smokes in the kitchen of her home in Bat Shlomo - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

“I was struggling to stay alive. I had chemotherapy, radiotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, and the side effects were terrible. That’s when they started adding synthetic THC to my IV,” she says. “But it gave me allergies. I suggested to the doctor that I use THC by smoking cannabis cigarettes, and he agreed. Me and ten other patients started smoking in the hospital and then at home.”

Some patients later claimed the right to self-cultivation. They obtained specific licenses, which encouraged the emergence of marijuana farms, initially non-profit, but which gradually evolved into a model of direct patient care.

Cannabis-based medication used by patient Hagit Yagoda on her home table in Bat Shlomo - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

“It became a mess. And the Ministry of Health appointed a committee to study the case, which discovered a device in the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs that allowed the cultivation and production of cannabis for medicinal purposes as long as a national regulatory agency supervised them,” he says. Yuval Landchaft, director of the Israeli Medical Marijuana Agency (IMCA), which was created in 2011.

Housed in the Health ministry during the command of the ultra-orthodox Yaakov Litzman, IMCA is chaired by a council composed of the ministries of Justice, Agriculture, Public Security, Finance, and Economy, in addition to the police and the IRS.

“Before, there was little research because there was no regulation for them. Today, we know a lot more about cannabis,” explains Landschaft. Among the most advanced knowledge in this field is the so-called “entourage effect,” the discovery that, in addition to cannabinoids, marijuana has flavonoids and terpenes that seem to interfere with each other, altering their effects on the body.

Production line of Bazelet, Israeli medical marijuana company - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

“The right combination of flavonoids and terpenes in certain proportions enhances the effects of cannabinoids,” explains chemist Ari Eyal, a retired professor at the Hebrew University and scientific director of Bazelet, a medical marijuana company created five years ago. “But the knowledge about the correct composition of each compound for each type of disease can take many years,” he predicts.

A biotechnology specialist and senior researcher at the Volcani Center, the state’s leading agricultural development center, Hinanit Koltai has been dedicated to studies on the entourage effect and the development of medicines.

The Volcani Center operates on different research fronts related to cultivation. Owner of a genetic seed bank dedicated to research and development, the center has been determining which parameters of light, water, and nutrients promote the presence of each component of the plant, in addition to testing, in partnership with the industry, the effects of the various combinations of molecules in artificial human tissues.

Employee handles marijuana on the production line of the company Bazelet, near Tel Aviv - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

“We have developed suppositories for inflammatory diseases of the intestinal tract, with very encouraging results, and also compounds for skin cancer that are especially active against malignant cells,” she explains.

“In the past six years, we have made huge strides,” says the scientist. “Since then, we have done so much research and discovered so much that I would risk saying that the therapeutic use of marijuana is a consensus in Israel, including among doctors,” she says.

Six years ago, psychologist Melody Dekel came to be threatened by doctors when she asked about CBD-based compounds for her son Daniel, then six years old, and diagnosed with autism two years earlier. He had been treated with amphetamines, antidepressants, and other medications.

“The responses were not only unsatisfactory but also caused regressions and psychotic effects,” she says, who says she reached the limit when a doctor suggested that the boy be admitted to a psychiatric clinic.

“I started looking for information and discovered a video of a mother of an autistic child who said she had had good results with CBD. It took me years to find a doctor who accepted this experience,” she says.

“With the oil, Daniel became less aggressive, stopped hurting himself, and started to do something very simple, but that seemed impossible before: to sit down and relax a little,” says Melody, who abandoned work and a master’s degree to become activist.

“The tragic thing is that just when we had to find an oil that looked like it was doing the best thing, the government launched, out of nowhere, a mega-reform that closed farms and sent us to pharmacies. And we lost the old supplier”, she fumes. “He has regressed again, and we are still in this situation.”

Portrait of Daniel, 12, who uses medicinal cannabis for autism, at the family home in Tel Aviv - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Melody refers to the medicalization of cannabis production for therapeutic purposes, undertaken by the government from IMCA in 2016.

The process has abolished clinics specializing in the therapeutic use of marijuana and replaced them with training courses for doctors. It also regulated the sale in pharmacies, and no longer with producers, and that the names of strains such as Black Widow or Moonrise would no longer be used. Instead, the designation of the compositions would be used as names.

Also, IMCA created rules ranging from acceptable practices for cultivation and manufacturing (which include the biological isolation protocol described at the beginning of the text) to acceptable medical practices. The change also created an electronic system of prescriptions and sales to avoid duplicate orders and encourage research.

The price of cannabis in Israel doubled from US$ 3.50 to US$ 7 per gram because of the costs of implementing the new rules.

“We know that some patients are, in fact, looking for recreational use. I admit that it would be easier if production for recreational purposes was legalized because then we could focus on what matters without concern for safety and justice,” says the director of the IMCA.

Since 2017, possession for personal consumption has been decriminalized, and the government has indicated its intention to legalize recreational use.

The regulation, divided into five books like the Torah, the holy book of Judaism, has been translated. The idea is that the more countries that adopt similar rules, the easier it will be to do business.

“We are a small country, but very innovative, and many of BOL’s 26 products were created from Israeli research,” says BOL Pharma’s Gedo. “Today, we treat cannabis like any other pharmaceutical product, and the perception is changing rapidly.”

Raphael Mechoulam’s laboratory at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress