A marijuana dispensary in Denver, where recreational sales have been legal since 2014 - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

Nancy Whiteman, 62, was not a cannabis activist before becoming an entrepreneur. “I had already used it, but I didn’t even know much about the medicinal properties. I heard about an acquaintance who was making soda with marijuana and thought there might be a business opportunity,” says the soft-spoken woman, wearing an elegant suit, at her company’s headquarters, Wana, near Denver.

The company started in medical marijuana and, with the legalization of recreational use in the state of Colorado, in 2014, entered this segment. “We tried various recipes until we arrived at gummies, which are the perfect vehicle for cannabis,” says Whiteman, who has 80 employees and manufactures 35 products in Colorado and operates in seven other states.

The release of production and sale sparked a race to open stores (so-called marijuana dispensaries) and companies that plant, refine, and manufacture cannabis products. More than six years later, the environment is one of consolidation. There are established brands like Wana, and less competitive companies have closed shop or been purchased.

Legalization in Colorado, the first in an American state, excluded anyone who already made money from marijuana. To this day, anyone who has a previous criminal conviction cannot work in the sector.

The legislation also didn’t expunge records of those with past convictions of trafficking or marijuana use, as California has been doing.

Licenses for marijuana businesses hover at a few thousand dollars, depending on the type, but the state requires new companies to have a business plan and a financial backing of US$ 250,000 (more than R$ 1.3 million), according to industry consultants.

The issues of background checks and costs limit the entry of minorities into this market because before legalization, non-white people were disproportionately arrested and convicted of marijuana-related crimes.

On the other hand, Colorado didn’t limit the number of licenses, as Washington and Oregon did, contributing to an innovative environment in the segment.

The Denver metropolitan area, the largest city, has 597 marijuana dispensaries for a population of 2.9 million, similar to that of Salvador.

Entering a dispensary like Lightshade in Federal Heights makes it clear that the sale of marijuana is far from being just that of flower for smoking –even though there are dozens of varieties of it available, as well as pre-rolled joints. Products range from extracts and oils for vaporizers to waxes, chocolates, sweets, and skin creams. Even intimate lubricant with cannabis is sold.

Top and bottom right, the store and growroom at Seed & Smith dispensary in Denver; bottom left, Lightshade dispensary - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

The customers’ profile is also varied: workers, housewives, elderly people with health problems, young couples, middle-aged men and women. Friendly “budtenders” (a pun that mixes “bartender,” or bartender, and “bud,” marijuana flower) patiently explain the products. Some arrive and already know what they are looking for, but many describe their need or desire and listen to recommendations (employees cannot prescribe specific products for a certain disease, like a doctor).

Chelsey Joseph, 30, saw this cornucopia of products as another type of business opportunity and founded White Label. The company plants and refines marijuana to produce products sold by other brands. With 35 employees, she takes care of manufacturing so that others can focus on marketing and distribution.

White Label makes, for example, cartridges for vaporizers and mouthpieces for the Jane West brand, created by the businesswoman of the same name, from Denver, whose focus is marijuana products for women.

West started making accessories, like pipes, because she thought that those that existed in the market, made of colored glass, were ugly. “I wanted to make objects that people would be proud to display at home, that fit into modern decor,” she says.

Entrepreneur Jane West, who sells marijuana products and accessories, in her home in Denver - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

“My client is a mother who smokes a joint before going to yoga, or who uses marijuana before cleaning the house, which makes the task more fun,” says the 42-year-old businesswoman.

Marijuana is not legal at the federal level in the USA, which causes problems for the three entrepreneurs. It is necessary to plant, refine, pack and sell the product in each state separately, since the plant and its derivatives cannot cross borders, even between two states in which the substance is legal.

“I cannot buy equipment that makes gummies on an industrial scale, because I cannot produce them in one place that has the lowest costs and distribute them throughout the country,” laments Whiteman.

Packaging rules also vary –some states require them to have child warnings; others require warnings about hazards. West has run into trouble importing her pipes from China, as the federal government classifies them as drug paraphernalia. Bank accounts and insurance are also problems, given that national banks operating in the country reject marijuana companies.

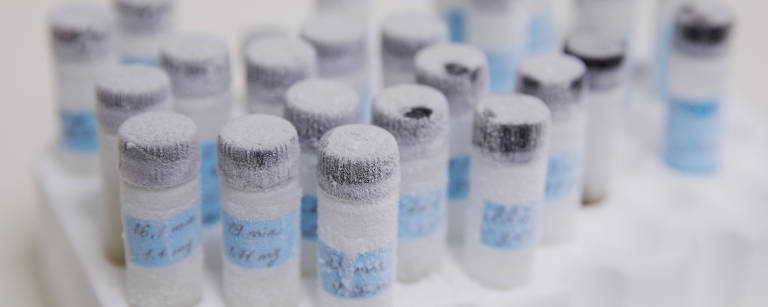

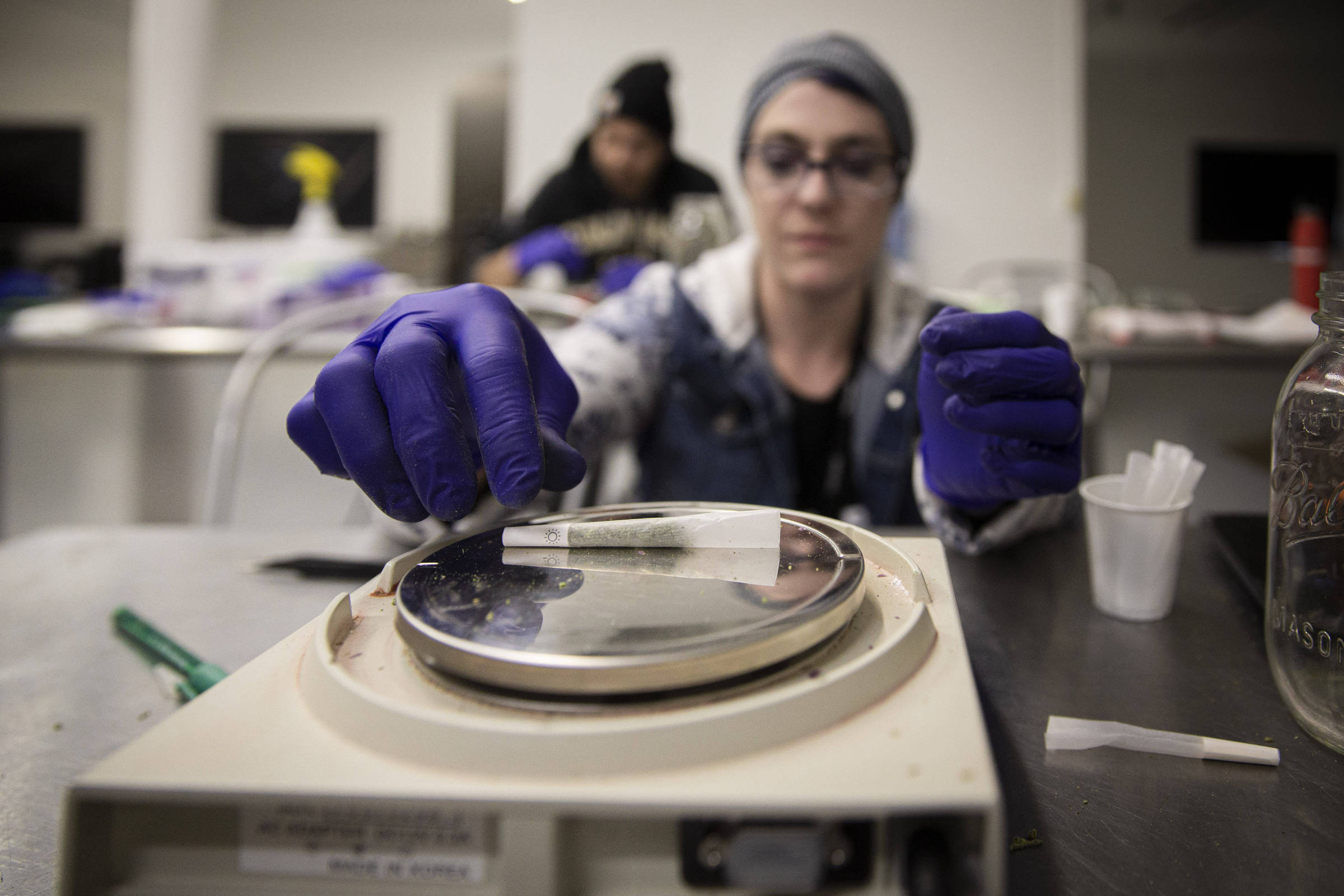

Employees roll joints at White Label manufacturing facility - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress

Despite the challenges, six years of legalization in Colorado proved the biggest fears related to cannabis to be untrue. A 2017 survey shows that marijuana use in the 30 days before the survey remained stable at around 19% among high school students; among adults, there was an increase in the proportion of users who used it, from 13.6% in 2014 to 15.5% in 2017.

Traffic accidents and drug-related hospitalizations did not explode, either, according to data from a report prepared by the Colorado government in 2018, in the fifth year after the law legalized the substance.

The coronavirus pandemic has brought greater acceptance, with more people convinced that the plant can help them deal with the consequences of social isolation such as anxiety, depression, and changes in sleep. More time at home, the only place where marijuana is legally allowed to be consumed in the state, also means more consumption opportunities.

In Colorado, the sector was considered essential, so factories and stores remained open. Internet sales, previously vetoed, were allowed –without home delivery: it is necessary to pick up the purchase in-store. Compared to the same period in 2019, sales increased by 23% from January to May this year.

Dispensary in Denver - Danilo Verpa/Folhapress