The urban population of Altamira jumped from 100,000 to 140,000 in just two years and turned the city into a chaos of traffic, violence and rising prices. On the other hand, it will gain thousands of new homes and the basic sanitation it has never had. Read the story of all that has been done or neglected in order to mitigate the impact of the construction on the life of the city

Street fight between Altamira citizens beside the XinguImage by Lalo de Almeda/Folhapress

Chapter 3 - Society

Altamira invaded

Every Sunday afternoon, especially after pay day, hundreds of workers gather in the ramshackle riverfront area of Altamira in search of entertainment. The cheesy techno music vibrates the amplifiers of bars on the banks of the calm, green waters of the Xingu where lots of drinking is done.

Women, some of them prostitutes, do a funky dance. Fights are common among men armed with knives and broken-off bottlenecks and women who pull on fistfuls of each other’s hair. The drunks who don’t collapse on the sidewalks or the sand, bathe in the river that receives the city’s untreated sewage.

The so-called “gold rush” that has gripped Altamira since 2011, when the Belo Monte dam’s construction sites were set up, has left deep marks on the city. Not all of them are negative. Some commercial sectors are booming, jobs abound for everyone, and salaries have increased

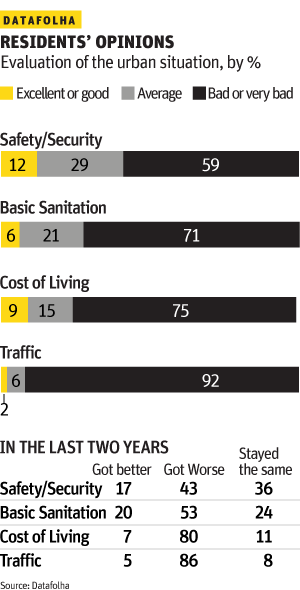

“Chaos”, however, is the word most people use, even those who defend the undertaking: chaotic traffic and public security and almost daily energy breakdowns that burn out home appliances. This is the result of the demand created by the dam, which consumes the same amount of electricity as 54,000 homes, pays a monthly energy bill of R$ 2.3 million ($1 million) and uses off-the-grid generators from 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. to attenuate the problem.

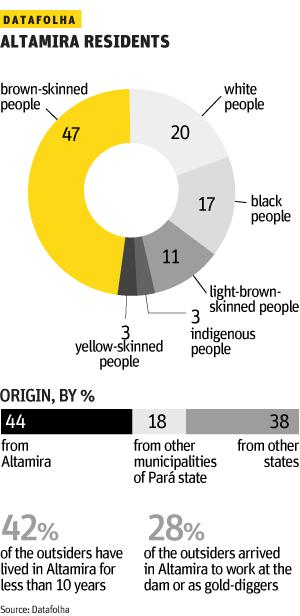

The city’s population, nearly 100,000 people when the 2010 Census was taken, has swelled to at least 140,000. The 18,000 dam workers expected during the peak of its construction, reached 25,000 in the second half of 2013.

The building of Belo Monte has affected 11 municipalities, but Altamira, the region’s main urban hub, has borne the brunt of that impact. But a distortion has been created by the fact that 92% of the construction takes place in the neighboring town of Vitória do Xingu, with one-tenth of Altamira’s population. In the last two years, Vitória collected R$ 121 million ($53 million) in taxes on municipal services, while Altamira collected only R$ 12.7 million ($5.5 million).

So it’s no surprise that Altamira residents are more critical of Belo Monte than the dam workers, according to a Datafolha opinion poll that interviewed 435 of the altamirenses. Although 88% of the workers approve of the construction, in Altamira this share falls to 57%, but, even so, a majority.

There is a clear perception that the dam’s main positive aspect is job creation (according to 66% of the residents), even though this can be a fleeting benefit: 44% of the residents think that the city will be worse off when construction ends, a percentage nearly equal to those who believe it will be better off (43%). It’s not by chance that this is the same share of residents (43%) who believe that Norte Energia is only partially complying with the improvements and compensatory benefits promised for Altamira.

Promises and debts

For the dam to receive an operating license, Ibama required Norte Energia to comply with dozens of compensatory projects with social and environmental benefits, an investment of R$ 5 billion ($2.2 billion) in the infrastructure of Altamira and the region’s other municipalities.

“It’s the biggest, ongoing social-environmental project in the world”, said Cassandra Molisani, the head of the consortium’s social-environmental department. “In the history of Brazilian dams, there is no record of as extensive and detailed a list [of such projects] as the one required for Belo Monte”.

Many of the projects are behind schedule and public services are overextended. The only hospital in Altamira that admits anyone must now care for new residents. “We are always 150% full”, said Waldecir Maia, the city’s health secretary. A new hospital is being built, with a 100-bed capacity, but should have been completed by 2012, not 2014, when it will be finished.

The health facilities are nearly the same size as the ones attending a population of 100,000. There are 16 basic units, or infirmaries, four of which were built by Norte Energia, and two of which already existed at other locations. “As I see it, this should all have been ready since the consortium came here”, says the health secretary.

José Lazaro Ladislau, the health manager of Norte Energia, attributes the overload put on the hospital to the city’s deficiencies in primary care. He agrees, however, that delays in building the hospital have occurred, but blames the city’s difficulty in finding an appropriate site and a delay in the project’s compliance with health surveillance norms.

“In any case, the current hospital is big enough to care for 200,000, in accordance with public health standards”, says Norte Energia’s health manager. Municipal health secretary Maia disagrees: This could statistically be true, but I welcome Norte Energia to spend one day at the hospital with me. For primary care, a good beginning would be for them [Norte Energia officials] to care for those at construction sites, without sending their workers to the city”.

“We’re already nearing the end of 2013, two years after the company came to the region, and the key pre-conditions are, practically speaking, only now just beginning”, complains mayor Domingos Juvenil of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), elected in 2012. Norte Energia defends itself by saying that the mayor’s office delayed in designating sites and approving construction at them. Marcelo Salazar, from the Altamira office of the Social Environmental Institute (ISA), an NGO, said that the mayor’s office is unprepared to deal with the population boom: “It’s an asymmetric negotiation”, he said. “The mayor’s office lacks the administrative structure to dialogue with Norte Energia”.

“All the accumulated pressure from a liability that has been decades in the making now comes to the surface,” said Cassandra Molisani, head of Norte Energia social-environmental department. She cites the example of the work to cleanup the city’s illegal dumpsites and the installation of a sanitary landfill. “Nowhere else in Pará state does a similar problem exist. Altamira was known as the city of vultures, a problem that has dragged on for at least 25 years”.

State military police on patrol in the “baixões” (Altamira’s neighborhoods on stilts)Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

State military police on patrol in the “baixões” (Altamira’s neighborhoods on stilts)Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

State military police on patrol in the “baixões” (Altamira’s neighborhoods on stilts)Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

State military police on patrol in the “baixões” (Altamira’s neighborhoods on stilts)Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

State military police on patrol in the “baixões” (Altamira’s neighborhoods on stilts)Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Warning sign on one of the houses on stilts reads: “Do not use drugs here. This is an order from the Military Police”Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

No firearms

The outfits and accessories of three military policemen (PMs) with the Tactical Operational Group (GTO) –black uniforms, submachine guns and a VW Amarok pickup whose sticker says that Eletronorte donated it– command respect in the dusty streets of Altamira. “I don’t take this vehicle and equipment [his hand slaps a gun barrel] out for recreational spins”, advises Carlos Gonçalves, the corporal in command. At the gas station where, at noon, our reporting vehicle meets up with theirs, the patrol is headed to one of the city’s “low-lying” areas, banks of flooded streams where houses built on wooden stilts abound and where most police raids occur.

In a half-decimated shack, between the last of the precarious footbridges, the PMs detain a thin, shirtless, tattooed man called Messias. “He’s already done nine years [of prison time] and been released”, the corporal announces. Beneath a house, in the middle of a mound of trash, the PMs find two knives and a crack pipe and decide to take Messias to the police station. A friend of Messias gives the detainee a São Paulo Soccer Club jersey to wear. The PMs search a shack facing that of Messias, where a young woman lies in a drugged stupor on a filthy sofa and remains indifferent to the comings and goings of policemen and reporters.

The only police station in the city has a staff of 17. The number of arrests for bodily injury has increased by 40% since 2010, says Cristiano Marcelo do Nascimento, the regional head of the Civil Police. “There has [also] been a big, 30% to 40%, increase in thefts and robberies, committed by gangs from [the northeastern Amazon state of] Amapá, from [the southwestern Amazon state of] Mato Grosso or from [the Pará state port city of] Santarém”.

In 2011, the year work began on Belo Monte, the police apprehended 22 drug traffickers. In just the first five months of 2013, there were 104 such arrests, mainly for crack possession. The number of adolescents arrested soared 196% in the first five months of this year, compared to the same period in 2012. Eight of ten of those imprisoned are youths, says Malaque Mauad, of the city’s Juvenile Protection Council.

Deaths caused by traffic accidents are another worsening problem. The road system remains unchanged, even though in three years the fleet of 10,000 vehicles has increased to 40,000, 68% of which are motorcycles. There are few sidewalks and lots of dust. “In the past, there were four [traffic-related] deaths per year. Now there are three to four per month”, says Flavio Carneiro, head of the city’s Transit Department.

Raw sewage from homes and commercial buildings in Altamira still flows straight into the Xingu River, since the treatment infrastructure has not yet been completedImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Waste piles up under houses on stilts in the Altamira “baixões”Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

An entire neighborhood on stilts that will be flooded from 2015 onImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Due to variations in the levels of the river, the houses on stilts are flooded only during the wet seasonImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Before being sealed off in October 2013, the dump site made Altamira famous as the “Vulture City”Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Workers lay down pipes for the new sewage collecting system in AltamiraImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Buses for construction workers of the power plant are the cause of gridlocks in the dusty streets of Altamira, whose traffic is now one of the main target of complaints from the local populationImagem: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Back and forth

Operating the controls of a R$ 1.3-million ($565,000), 74-metric-ton bulldozer, Aparecida Torres, 28, talks about having left her job as a municipal school teacher in Altamira to unload two barges of sand per day at the Belo Monte construction site. “I used to earn R$ 1,600 ($695) per month and now I earn R$ 3,200 ($1,390) per month. I miss the classroom, but I had no perspective [of increasing my income]. Now I pay my bills and can save some money”, she said.

At least one dozen commercial gyms have set up shop in Altamira in the last two years, where fees can reach R$150 ($65) per month. Middle-class buying power has shot up in the city, thanks to Belo Monte. “Sales have increased by an average of 35%”, celebrates Odair Pinho, vice-president of Acepa (the commercial association) in Altamira.

Salaries have gone way up because a scarcity of manpower has handicapped the region’s traditional activities, like planting and tending to cocoa trees. “A worker’s wage used to average R$ 25 ($11) per day. Now it’s R$ 40 ($17) to R$ 50 ($22) per day, and even still, it’s hard to find manual laborers”, complains José Carlos da Silva, president of the Altamira association of growers who sell their produce at street markets.

The cost of living has increased, with real estate setting the pace: an 80m² house in the heart of Altamira that once cost R$ 200,000 ($87,000), now can’t be bought for less than R$ 400,000 ($174,000). Norte Energia alone rented 123 business properties in the city (at different periods of time). Foodstuffs are also getting pricier. “What used to cost one real at a fair today costs three reais”, grumbles shopkeeper Elivan Gomes, in between the stands of the Municipal Market.

Altamira never had a sewage collection system. The water distribution network reached no more than 40% of all homes. Street-side trenches and cesspool-type backyard pits for dumping untreated sewage were standard in the city, until Belo Monte arrived.

To get a license for the dam, one of Norte Energia’s obligations is to install 180 km of water distribution pipes and 220 km of sewers, along with the collection and treatment of 100% of the sewage of Altamira. Quite a novelty for the northern region of Brazil, in which only 22% of urban residences have basic sanitation.

In Altamira, more than two years after the beginning of dam construction, the basic sanitation works are far from completed. The intermediary pump stations and the main one for sewage treatment are still being constructed. Even still, an optimistic Marcelo Dias, the head of such Norte Energia projects, believes the company will comply with its July 2014 delivery deadline.

“There was a delay in beginning work on these projects because of a complex negotiation with the mayor’s office and with Cosanpa [Pará State Basic Sanitation Company], that will operate the system”, affirms Dias. Everywhere in town, street pavements are being broken up to dig trenches and lay pipes, which turns the traffic even more chaotic.

Once a riverbank-dweller, João Batista da Silva Balão contemplates the Xingu River at a camp site in front of the place where his farm used to beImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Land prepared for the construction of 4,100 houses in AltamiraImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Houses under construction by Norte Energia in the neighborhood of Jatobá, AltamiraImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Houses under construction by Norte Energia in the neighborhood of Jatobá, AltamiraImagem: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

The uprooted

João Benedito da Silva Balão, 70, lived nearly his entire life on the banks of Xingu’s Big Bend. He had a farm that faced the river at the spot where today, trucks and tractors go to and from the canal being constructed. He received R$ 700,000 ($304,000) for his land, bought a house for his children in Altamira and a plot of land in Medicilândia, around 80 km from the Xingu.

“I sold rice, flour, and black beans. I was used to living on the riverbank and had little desire to leave, but I also had no choice,” he recounted. “Today, the solitude that I feel is the worst you can imagine. I miss too many things. It’s a punishment from God. He’s going to destroy all of the animals, the paca and the cutia [two forest rodents, resembling guinea pigs, but larger], the deer, and the caititu [the white-collared peccary]. They’re all going to perish”.

Norte Energia has, on its books, the purchase of 1,100 rural properties, now occupied by the construction sites or areas nearby. Public defender Andreia Barreto estimates that around 2,000 families who depended on fishing and agriculture were adversely affected by the dam and most of them indemnified. “Some were well paid and others were not. Many lost the livelihoods and lifestyles to which they were accustomed. They don’t know what to do with the money”, she said.

Those who didn’t accept Norte Energia’s offers were evicted, with the value of their property deposited in an escrow (third-party) account. According to Luiz Zoccal, head of Land Title and Relocation department for Norte Energia, only 4% of negotiations ended with evictions.

The main bone of contention between the evicted and Norte Energia is the value placed on improvement they made on their property, like cocoa plantations common in the region. Zoccal explains that the value of these upgrades varies in accordance with the price of the product on international commodity markets. “[Commodity] prices were [downwardly] revised. Cocoa had already climbed to R$ 10 ($4.30) per kilo, but is now between R$ 4.50 ($2) and R$ 5.50 ($2.40) a kilo”.

Maria do Socorro de Oliveira, 69, lived on 200 hectares next to a road widened for the passage of trucks and tractors at the Pimental construction site. She had a 4,700-tree cocoa plantation. Each tree was given a value of R$ 12 ($5.22), a price that she contested because a neighbor who had earlier sold his property, received more than double the price per tree that she was offered.

So she was evicted from the property. “I went to town for a doctor’s check-up and when I returned, my house had been demolished”, she said. While she awaits a [court] decision regarding her indemnity, she lives with her daughter and grandchildren in a house on stilts in Altamira. To help pay the bills the family rents the porch of the house, where a bar is open for business.

In Altamira, Norte Energia registered 7,790 families in areas to be inundated, many of them living in houses on stilts. They’ll have to leave their homes by July 2014. Around 4,100 of them agreed to being relocated in houses that Norte Energia began to build by mid 2013. The others will be indemnified. Public defender Andreia Barreto believes that the number of those to be indemnified has been underestimated.

There are complaints about the one-size model for these houses which measure 63 m² –three bedrooms (one with its own bathroom), another bathroom, a living room and an American kitchen– to be built on lots of 300 m². The first brochures that Norte Energia distributed in Altamira showed three sizes for the interior space –60 m², 69 m², and 78 m²– for houses made of mortar and brick. Because of the delays, the company opted for building the houses with alveolar concrete because, despite 20% higher costs, this type of concrete, injected with air bubbles to provide more “thermal comfort”, results in a temperature that is 5 degrees Celsius lower than the outdoor one, the company says.

The relocation of families is among the Belo Monte compensatory actions facing the longest delays. The original forecast was to begin construction of the houses in 2011, but, once again, the mayor’s office delayed in choosing where and on what type of terrain the housing would be built.

Brickmaking in an area of the Panelas igarapé (river) that is going to be displaced by permanent flooding - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Brickmaking in an area of the Panelas igarapé (river) that is going to be displaced by permanent flooding - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Brickmaking in an area of the Panelas igarapé (river) that is going to be displaced by permanent flooding - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Brickmaking in an area of the Panelas igarapé (river) that is going to be displaced by permanent flooding - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Brickmaking in an area of the Panelas igarapé (river) that is going to be displaced by permanent flooding - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

One of Belo Monte’s biggest urban dramas is the plight of the pottery workers who live in a 2 km² region that will be inundated. “This is the one permanent trade that will end forever here. We are at luck’s mercy”, protested Marconi Ribeiro, with the union representing them. “The clay here is good, which is why we live and work in an area that will be flooded during the rainy season. There is nowhere else to relocate us [near a clay supply] close to Altamira”.

All of these potters are squatters who plan to demand R$ 200,000 ($87,000) apiece in indemnities, despite their not having land titles to prove legal occupation. Negotiations with Norte Energia have barely begun. The flooding is forecast for December 2014.

Brickmaking in an area of the Panelas igarapé (river) that is going to be displaced by permanent floodingImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Lula’s gospel

“This country needs more energy and I understand that to generate it, dams must be built. But not the way that this project is doing so”, laments Erwin Kräutler, who has been a Catholic bishop in the Xingu region for 32 years. “And now there is no turning back. The PT [the Workers’ Party to which President Dilma Rousseff belongs] is one of the biggest disappointments of my life. Lula [Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Rousseff’s predecessor] lied to me when he said that the project would only be approved if it benefited everyone, without being forced down people’s throats”.

When Lula visited the Belo Monte region in 2010 and defended the building of the dam, a rift was created among social movements organizing around the issue. Until then, they were united against building it.

The FVPP (The Foundation to Live, Produce, and Preserve), one of the most traditional NGOs, switched sides. “We decided to accept the project as a reality, in part, because its [the dam and reservoir’s] original design was much more [socially and environmentally] deleterious. We thought it was time to give up our zealous resistance. We were widely criticized for doing so, but we decided to adopt a spirit of negotiation”, justified João Baptista Uchoa Pereira, the foundation’s coordinator.

The FVPP decided to more intensely stick to its original mission, to support family agriculture. The NGO, doing social outreach for over 20 years, works on behalf of 10,000 small farmers and brings together 70 associated entities. “Belo Monte always concerns us. It brings good things, like the possibility of transforming the municipality, and it brings bad things”, says coordinator Uchoa Pereira. Odair Pinho, from the commercial association, agrees: “Many improvements have been made. But a new challenge will arise: lots of people will be without jobs [after the dam has been built]”.