$2.2 billion have been reserved by Belo Monte for social and environmental compensation, part of which is intended to better the living conditions of nine indigenous peoples, but riverbank-dwellers were left out of the plan. Take a trip with Folha to the land of the Juruna and the Araweté and to the Rio Xingu Extractivist Reserve

Aritã’ihi from the Araweté village of Paratati in front of a fire over which pieces of wild boar are being roasted (dozens were killed while they crossed the Xingu)Image by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Chapter 4 - Indigenous peoples

Indians don’t want handouts

You don’t have to leave the city limits of Altamira to confront the Indian issue triggered by the Belo Monte dam. A few blocks from the city center, on Coronel José Porfírio street, the local office of the National Indian Foundation (Funai), the policymaking body for indigenous peoples, is the unvarnished portrait of a government agency under stress: grimy walls; few employees within eyesight; four new Mitsubishi pickup trucks, one smashed up from an accident; and a VW van that is falling to pieces.

A crowd of Indians sprawls on the patios and in the gardens, some up them resting in hammocks. Most are women and children, lots of children, who defecate with complete nonchalance in a lot that is part of the campus of the Federal University of Pará State. On the Tuesday in September when Folha’s reporting team was, for the first time, at Funai offices in Altamira, a non-stop flow of women arrived to pick up documents needed to receive government benefits paid to working mothers. In September alone, 400 Indian women filed for such benefits at that office.

Numerous families take advantage of the trip from the village to the city, one that can last from several hours to several days, to sell handicrafts and buy processed food. “We even buy cassava flour”, laments Giliarde Juruna, leader of the Muratu tribe of the Paquiçamba Indigenous Land.

Cassava root cultivation and the flour ground it from are the Indian’s main culinary contribution to Brazilian cuisine. To depend on the white man to put cassava flour on their plates (actually eating bowls made from gourds) is the worst symptom of dependency that the region’s Indians, impacted by the dam, have developed in relation to it and Norte Energia.

The Juruna tribe of the Paquiçamba and the Arara tribe of the Big Bend are the only groups that the environmental assessment for Belo Monte included in the area directly impacted by the dam because their lands are located on this curve of the Xingu that the Pimental dam will nearly leave dry for most of the year. Seven other indigenous lands were designated at being indirectly impacted, which, in principle, gives their inhabitants less right to receive compensations required by Belo Monte’s Basic Environmental Project (PBA).

The fight of the Kayapó

The Munduruku and Kayapó peoples, the latter led by legendary Chief Raoni Metuktire, both of whom made the most noise about Belo Monte, are not on this list. The former don’t even live in the Xingu River Basin, but rather, in the Tapajós River Basin and, more than once, paralyzed work on the dam to pressure the government to drop plans to build five dams in the Tapajós Basin, another tributary of the Amazon River.

Raoni’s people inhabit a region of the Xingu some 500 km upriver from the Big Bend. But these Kayapó are convinced that the government will not give up the idea of building more dams upriver from Belo Monte (despite a 2008 National Energy Policy Council resolution that stated that Belo Monte would be the Xingu River’s only dam). Since the 1980s, this tribe has stood out among those who opposed harnessing the river’s potential.

“Belo Monte’s low energy generating capacity should create pressure to build new dams on the Xingu River”, says Marcelo Salazar, coordinator of the Social Environmental Institute’s (ISA) office in Altamira. “I pray that the government honors its commitment not to mess with the river anymore, but in Belo Monte’s case history, there’s an anthology of commitments made, but not honored”.

Dotô Takakire, a Kayapó from the Baú-Mekragnotire Indigenous Reserve, and technical coordinator of Funai in the town of Novo Progresso in Pará state, repeats in clear Portuguese, the notorious threat that his aunt Tuíra made nearly 25 years ago when she pressed the blade of her machete against the face of Eletronorte engineer José Antônio Muniz Lopes: “The government consults, but it constructs, no matter what. When the next dam [on the Xingu] is built, there will be war”.

For the Indians, Belo Monte has become an irreversible and divisive fact. Even among the Kayapó, Norte Energia’s undertaking has caused internal divisions. The Xikrin tribe, a Kayapó sub-group in the Indigenous Reserve of Trincheira Bacajá, became one of the company’s major clients. For over a year –from 2011 to 2012–, Norte Energia, even before making indigenous compensations required by the PBA, distributed R$ 30,000 ($13,000) per month to each village in the form of goods. Even Mitsubishi pickups could be seen in indigenous lands. The pacifying monthly allowance received the misleading name “Emergency Plan”.

Other Kayapó from Pará state began to negotiate with the electric sector, but the deals being discussed foundered this past March. In a letter addressed to the Eletrobras holding company, they renounced the promise of R$ 4.5 million ($2 million) a year in “dirty money”, for 26 indigenous communities. “Your word means nothing. End of conversation”, says the text. “Our river doesn’t have a price tag. The Xingu is our home and you are not welcome”.

Although outside the area of Belo Monte’s direct impact, the Xikrin tribe fear for the health of their river, the Bacajá, which empties into the Big Bend. With the drastic reduction in the flow rate of the Xingu below the Pimental dam, the condition of the Bacajá will also change, but in what way, it remains unknown. “There was a huge protest against Belo Monte, [but] our relatives [the Xikrin] here on the Big Bend accepted its construction. We can’t do anything more”, said a resigned Dotô Takakire about this capitulation.

Unpayable debt

Brazil has several hundred, distinct indigenous peoples, each with its own language and traditions. But a common trait is an aversion to avarice in others. Tempted by the influx of goods from Norte Energia, which is anything but miserly, they always ask for more.

“The Indians let themselves be had. Many chiefs were bought”, says a disapproving Elza Xipaya, from Funai in Altamira. “The Indians allow themselves to be bought, but they don’t sell themselves,” adds anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, with the National Museum of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “The Indians of the Big Bend were increasingly forgetting that they were Indians. With Belo Monte they discovered that, juridically speaking, they are Indians and began to fight for their rights. As paradoxical as this seems, this is positive. They developed a political identity”.

During the 1980s, Viveiros de Castro lived with the Araweté tribe, one of the indigenous peoples within the dam’s indirect sphere of influence, which is not to say that it caused no harm. With the “technological compression of space” made possible by telecommunications as well as speedboat and plane transport, there are increasingly more Indians in cities and increasingly more white men in indigenous areas.

The Emergency Plan’s pouring resources into Indian villages triggered the “classic and lethal impact caused by mitigating impact”, says Viveiros de Castro. His doctoral student, Guilherme Heurich, who lives part of the year in the Paratati village of the Araweté tribe, shares this opinion. “The way in which houses were built shows that the intended compensation for the harm the dam caused is, in fact, another type of impact. By sawing timber inside indigenous lands and bringing tons of construction materials to villages, Norte Energia causes an impact rather than compensates for it, as should be the case”.

Heurich is referring to the wooden houses that the company built in the Paratati village, six hours by speedboat upriver from Altamira this time of year, if the skiff has a 90 HP outboard motor. Houses made with wooden panels, 8 m x 10 m in size, floors of cement, and fiber cement tiles on the roof, contrast markedly with houses made of clay and palm-straw roofs. Such roofing ventilates and cools the houses’ interior temperatures, but the straw needs to be replaced every five years. The public prosecutor’s office, a mediator in negotiations with Norte Energia, suggested the use of clay roofing tiles. But this would delay construction and the Araweté tribe didn’t want to wait.

The wooden panels were made from Brazil-nut trees, a species whose cutting is prohibited, at least outside indigenous lands. Kamarati, the leader of the Paratati village, said that Indians were the ones who chose Brazil-nut wood and that the only trees sawn were those that had fallen or had low yields.

Environmental engineer Fernando Augusto Di Franco Ribeiro, 36, Norte Energia’s acting head of indigenous affairs, said that the building of houses for all of the villages of nine indigenous peoples impacted by the dam was neither the result of the Emergency Plan (which ended in 2012) nor of the PBA, which only got under way in the second half of this year, but of a separate negotiation. Such talks aren’t always cool-headed: the Assurini tribe of the Koatinemo reserve and the Xikrin tribe of the Trincheira Bacajá land, demanded masonry (usually brickwork) construction. But Norte Energia said that this was out of the question.

Whatever similarity exists between this relationship pattern and that of the Emergency Plan is not coincidental. It reflects the nature of the white man’s attitude: the company gives what it wants and the Indians end up accepting it.

The Araweté village of Paratati, where Norte Energia builds new homes with fiber-cement tiles and planks from Brazil-nut treesImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Aritã’ihi weaves a piece of red cloth for the Araweté traditional skirt at the Paratati villageImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Araweté boy ready to jump into the waters of the Xingu RiverImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Shopping list

The Emergency Plan’s monthly allowance, besides encouraging the mushrooming of villages (there were two Araweté villages; now there are six), was the result of the so-called “shopping lists”, which included everything from speedboat motors to yogurt, from radios to frameless beds. “A truckload of Indians appeared”, says Elza Xipaya, Funai’s technical coordinator in charge of handling the orders. “Our structure fell apart. There was no longer tranquility. Today, Funai [in Altamira] is in chaos. Everything depends on Norte Energia”.

To complicate the situation, in late November, reports from isolated Indians in the region of Xipaya tribal land, surfaced. The Ethno-Environmental Protection Front of the Middle Xingu, an arm of Funai’s Altamira office, headed by Luciano Pohl, and in charge of 11 villages of three, recently-contacted indigenous peoples, has only seven employees and is knee-deep in paperwork. A simple expedition to confirm these accounts (only footprints were found) requires at least one employee’s spending more than a week to reach his destination.

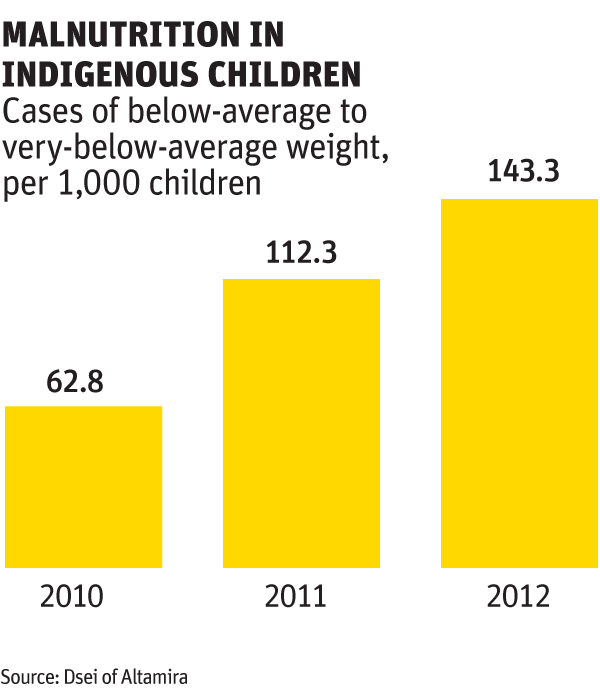

In old villages, cassava fields began to disappear. In the new ones, the huts for making cassava flour weren’t even built. With the change in eating habits, one which favors processed foods bought in the city, malnutrition paradoxically increased.

The Emergency Plan was suspended in 2012 because of widespread criticism. The geologist Pedro Bignelli, 52, a former Ibama licensing director who now coordinates Norte Energia’s indigenous department, is in charge of negotiating a truce and putting the village-improvement program back on track. “I spoke with the Xikrin: ‘You are becoming a dependent people, like those in wheelchairs’”, he recalls. “It was a tense meeting, but they understood”.

Norte Energia undertook other construction efforts, envisioned in the indigenous component of the PBA, like landing strips, basic sanitation, docks, roads, artesian wells, health clinics, and schools. But most of the programs that made up the plan will be managed by Verthic, a third-party company, composed of what remains of a group, led by anthropologists, in charge of studying the dam’s impacts on indigenous peoples.

Fernando de Freitas Vicente, 35, who heads Verthic, is a manager who sees some merit in the Emergency Plan. For him, it made sense, because no other plan preceded it. But the way in which it was executed was tragic. “The idea was to strengthen Funai sufficiently to mitigate the [dam’s] impact [on Indians], while the PBA was not yet underway. But Funai and Norte Energia are riddled with incompetence; they only have money”, said Vicente, who recounts having seen bales of rice and beans on the list of goods to purchase, being used as makeshift steps on the Indians’ riverbank shacks. “The Belo Monte undertaking, despite its ordeals, is a change in the wind”, says the administrator, referring to the unprecedented nature of the indigenous component of the PBA.

A river of swine

No bales of rice and beans serve as steps for the riverbank shacks of the Paratati village in the Araweté Indigenous Reserve. Women and children, among them the local nurse, wash clothes in waist-high water. Girls and boys occasionally wade out to climb a tree and jump into the Xingu.

At the top of the ramp that leads to the houses, a trail of smoke rises. Various blackened cuts of meat from boars (wild pigs) are being roasted. Dozens of boars were killed at their most vulnerable moment, when the entire herd of swine, several hundred animals, crosses the river. Herculano Costa Silva, 46, the riverbank dweller who travels with the reporting team to Paratati, having received a radio-transmitted invitation from Chief Kamarati, brings a gift of three home-grown watermelons and receives, in exchange, three-quarters of a boar. “Indians befriend us all the time”, says Silva.

In 2001, land grabbers burned down this riverbank dweller’s home. Costa Silva moved to Altamira, then to the town of São Félix do Xingu, jumping from place to place as a gold digger, but ended up returning to where he was born and raised. He was among those who fought for the creation of the Rio Xingu Extractivist Reserve that is now home to 59 families in a swath of Xingu riverside land. At the signing of the act that created the reserve, on June 5, 2008, Environment Day, Silva gave a speech next to then-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

His friendship with the Indians of the Paratati village doesn’t stop Silva from bitterly complaining about the discrimination felt by those who live on the extractive reserve, which was not included in the PBA. Even though the reserve lies directly across from the land of the Araweté people, on the other side of the Xingu, and those who live there are subject to the same impacts as those suffered by the Indians, they will not receive any benefits to compensate for Belo Monte.

“We are made of the same human flesh and bones [as the Indians]”, says a resentful riverbank dweller. The health clinic and the recently-build school in the Gabiroto community, still without municipal workers, were financed with funds from other sources, like Brazil’s Vale Fund, Norway’s Rainforest Foundation, and the Moore Foundation of the United States.

Inside the home of a rubber-tapper, Gabiroto community, in the Rio Xingu Extractivist ReserveImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Home of the riverbank-dweller Herculano Costa Silva in the Rio Xingu Extractivist ReserveImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Riverbank-dweller Herculano Costa Silva brushes his teeth in the waters of the Xingu RiverImage by Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Despite the light-colored eyes of a few of those in the Paratati village, it’s obvious to anyone from outside the village, that they are all Indians. Except for the dozen workers who have built wooden homes there. The Indian men wear loose-fitting shorts and colorful bermudas and can almost be mistaken for workers. The women, however, wear the short, red skirt of the Araweté tribe that they themselves weave from cotton that they plant and dye. Some also paint their faces and hair with the same color, which comes from the reddish oil of the urucum seed.

Who is an Indian?

The Araweté village of Paratati is very different from the Juruna village of Muratu in the Paquiçamba Indigenous Reserve, one that could be easily be mistaken for communities of river-dwellers. Homes made of wooden planks arranged in rows, all of them lilac-colored, have nothing in common with the labyrinth of new and old houses in Paratati. Muratu can be reached by car, much of the trip on a road paved by Norte Energia, so-called travessão 27 off the Transamazônica highway that cuts through an area where the dam is being built.

The Juruna village of Muratu, at the Big Bend of the Xingu River - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

The Juruna village of Muratu, at the Big Bend of the Xingu River - Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Everywhere, there are visible signs left by Norte Energia’s Emergency Plan, for better or for worse. There’s a new school built of bricks. But in September it was still not being used, for lack of a teacher. In the sand of riverbank beaches, various objects are scattered, from aluminum skiffs, fishing nets and outboard motors to pieces of toys, plastic packaging and childrens’ clothes.

Chief Giliarde Juruna’s only complaint about the Emergency Plan, however, was that it ended. “It was supposed to continue, R$30,000 ($13,000) per month, until the PBA begins. They say that the PBA began, but for me it didn’t start”. Without donations, the village had to return to its fields and is now preparing to build a hut for making cassava flour.

What irritates the Jurunas is the slow pace of the process of enlarging the area of the reserve, something needed to give Indians access to the dam’s reservoir to fish. What also remains up in the air is whether a bridge will be built over the Belo Monte canal so Indians can reach Transamazônica’s travessão 27 to arrive in Altamira. Without it, they will have to make a detour via travessão 55, which would force them to drive 28 km more to reach Altamira.

The leader of the Muratu village says that the Juruna of the Big Bend still face discrimination because its members don’t look like Indians, which makes recognizing their rights more difficult. This, despite their having lived on government-demarcated Indian land since 1991. “I say I am an Indian and that is that. I put my hand on my chest. Whoever knows us knows that we are Indians. I don’t depend on anyone”.

Urban tribe

For urban Indians who have no connection to traditionally-occupied land, their last resource is a genealogical one. Altamira was built on the stretch of the Xingu where the villages of the Xipaya and Kuruaya peoples were located, tribes that diluted their racial heritage by miscegenation with migrants from other regions of Brazil.

Because social-environmental requirements surrounding Belo Monte also envision the relocation of non-tribal-village Indians, suddenly many people who lived in to-be-inundated urban areas began to call themselves Indians in the hope of getting a house from Norte Energia, or else financial indemnities, or a letter of credit.

Elza Xipaya, herself a distant descendant of tribal Indians, formed an association of Indians from the city so that Funai would recognize them. When Norte Energia began to register indigenous urban descendants, it recruited her as a kind of consultant. “My job was not to allow false Indians to register”, she says. She began to work with sociologist Mayra Pascuet and biologist Mariana Favero who started the registration and afterwards set up Apoena, a company that Norte Energia put in charge of overseeing the relocation of urban Indians.

The criteria for separating Indians from non-Indians are declaring oneself an Indian and/or being recognized by the ethnic group, by means of interviews and genealogical reconstruction. In the case of ethnic groups from distant places, the team relies on regional Funai offices. The registration effort, begun five years ago, ended in January 2013, with 654 indigenous families registered in the urban area of Altamira and 98 others in the rural area.

Declaration of independence

It’s not only the Norte Energia-provided houses that motivate Indians and non-Indians, inundated or urban, to seek out a share of the resources that Belo Monte brought to the region. Besides the more than R$ 4 billion ($1,7 billion) from the PBA, the federal government has earmarked R$ 500 million ($217 million) for the Sustainable Development Plan for the Xingu Region (PDRSX). This year alone, R$ 40 million ($17 million) is being allocated to capacity-building and community-improvement projects.

In the first week of September there was a PDRSX meeting in Altamira. Dotô Takakire of the Kayapó, wearing a striped, button-down shirt and pointed cowboy boots, defended the government’s donating R$ 600,000 ($261,000) to build a 300 m² support center in Castelo dos Sonhos (an Altamira district 950 km from the city’s administrative headquarters).

With that support center, 255 families from five villages of the Baú-Mekragnotire Indigenous Reserve can more easily obtain government benefits and services. These include: Bolsa Família (monthly government welfare payment to poor families), benefits to working mothers, and social security benefits for retirees. The project was approved.

In the hall of the auditorium of the Commercial Association, where the PDRSX meeting was held, a quote below a portrait of Abraham Lincoln (and questionably attributed to the 16th American President) seems custom-tailored to characterize the relationship between Indians and non-Indians caught in the wake of Belo Monte: “You cannot help men permanently by doing for them what they could and should do for themselves”.