Cerro Corá Community, south of Rio, seen from the viewpoint Dona Marta - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

Orelha is 22 years old and has several marks on his arm. He held a rifle for the first time at the age of 13. Since then, he has commanded drug dens in Rio de Janeiro, and today he leads a faction in a Rio de Janeiro favela.

Like so many others, it is a favela with a bustling shopping center that resembles that in a country town. Sound cars advertise promotions, motorcyclists ride without a helmet, and people greet each other going to and from work.

Further up the hill, boys sit on makeshift three- and four-story buildings with pistols at their waist and exchange information over radio transmitters about everything happening on the ground. They spend their days expecting to be invaded by rival drug factions or attacked by police. They define themselves as criminals.

When the reporter arrives and identifies himself, they send messages and authorize the ascent. Orelha and Perverso, 26, send the team to a room. Tattoos mark their bodies. They explain that they are part of the drug trafficking chain in the region. Other people follow the conversation.

They are armed and carry grenades, but they do not act manacing. They agree to pose for photos, their faces covered by T-shirts. They say that we can ask whatever we want, as long as it is not recorded in the text of which slum they are, and do not reveal their real names.

“I got into crime because my whole family was involved, cousins, brother. I had no way of mirroring myself in other things,” says Perverso.

Orelha says he started because of the money and that nowadays, he likes being a drug dealer. “I already made a lot of money, and I haven’t left. I enjoy being this way, you know? You can deny it, but this way, many [respect] us. And we aren’t here to be oppressed by anyone, understand? "

The two traffickers say they have already been arrested for murder and are on the run. They are part of a criminal faction that has tentacles all over the country. The faction’s primary source of income is drug trafficking.

They say that the sale of illicit substances will not end, even with police intervention. “One dies, another is born,” says Orelha, who says that they are not the cause of the violence: “If they [police] do not come here, we will not go to them. But if they do, shots will be exchanged”.

The holes in the walls of the hill’s alleys confirm the threat. Statistics too. Rio de Janeiro is a violent state, with a rate of 37.6 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, higher than the national average of 31.6.

It is the result of a dispute between the criminal factions that fight among themselves for control of territories and markets and with the Civil and Military police –who themselves are responsible for one-third of the murders in the city, according to official data.

Rio is a microcosm of national violence and an emblem of Brazil’s failure to deal with illegal drugs by violent confrontation, leading to incarceration en masse.

In celebration of the first 100 days of his government, President Jair Bolsonaro launched the new National Drug Policy with the then Minister of Justice and Public Security, Sergio Moro. Despite also involving the ministries of Health, Citizenship, and Family, the focus of the text is on combating organized crime and using repressive actions to reduce the supply of illegal substances.

The text says it takes into account that drug legalization is mostly opposed by the Brazilian population. Indeed, the 2018 Datafolha survey shows that two out of three Brazilians say they are against the legalization of marijuana in the country.

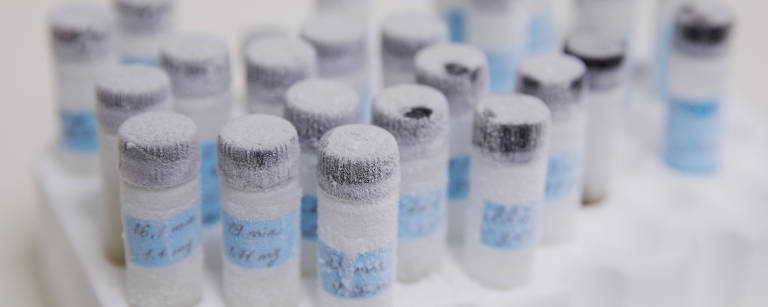

The policy also highlights the sale of goods seized from drug trafficking (amounting to R$ 92 million in the first half of this year) and the intelligence gained from recent operations. Experts have praised the work. The Caixa Forte operation, launched in late August, had more than 400 arrest warrants to dismantle the PCC’s financial arm and blocked more than R$ 250 million. At the end of September, the King of Crime operation blocked R$ 730 million from the faction.

Movement on Estrada da Gávea, in Favela da Rocinha, in the south of Rio de Janeiro - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

The federal government has acted against proposals for flexibility. In early September, the Minister of Justice, André Mendonça, sent deputies a motion to repudiate bill 399/2015, which proposes to legalize the cultivation of cannabis in Brazil for medical and industrial use.

The letter highlights the harmful effects of chronic marijuana use and says that drug use is a serious public health problem that impacts family and society. Finally, it states that there has been an increase in the use of cannabis in countries that have relaxed control.

This is not true. Studies by Brazilian psychiatric epidemiologist Sílvia Saboia Martins, from Columbia University, show no significant change in the use of marijuana by adolescents in the American states where authorization for medical use occurred.

Her research is based on the detailed National Survey on Drug Use and Health in the United States (NSDUH) and concludes that, even where recreational use was allowed, there was a slight increase in consumption only after the age of 21; among male adolescents, there was even a setback.

University of São Paulo professor Leandro Piquet Carneiro, a public policy specialist, says that there are two positive things about how Brazil treats drugs: an active public health sector to treat addicts and the fact that the legislation is lenient with users. For him, as long as we live in a drug prohibition regime, there are few alternatives to managing public security.

“We live in a cocaine-producing region, alongside three producing countries [Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru]. This impacts the availability of the drug, here, with crack, with the spread of consumption centers throughout the country, which has a very strong criminogenic effect. There is also a dispute over retail outlets. The international prohibition system forces countries to have a response through [public security],” he says.

Traffickers Orelha, 22, and Perverso, 26, who said they have committed murder and are on the run, show guns in a favela in Rio - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

Police chief Orlando Zaccone, who studied trafficking in his master’s dissertation and is the author of the book “Shareholders of Nothing –Who The Drug Traffickers Are,” defends the legalization of drugs because, in his words, trafficking is a victimless crime.

“The user is not a victim because even he is criminalized. Public health is hurt much much more by the ban,” he says.” There is nothing that offends public health more than a war.”

The hairdresser Raquel Sabino, 24, lost her father, Sebastião Sabino da Silva, in a violent confrontation that lasted more than a week in Jacarezinho, in the north of Rio, in 2017. The Paraíba trader moved to Rio to support the 13 brothers after losing his father. He started with a potato chip stand, bought another one of corn, and expanded the business until he acquired a liquor store when he already had seven children.

Raquel Sabino, Jacarezinho resident whose father, Sebastião Sabino, was killed by the police - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

In 2017, he was nervous about his youngest daughter’s disappearance during a police operation and went looking for her. He was shot three times by the police on the street: in the neck, in the mouth, and in the heart.

“He was so strong that he still managed to get to the sidewalk and ask for help. He was in agony for about 40 minutes, and the police said they were not going to help him because he was a drug dealer [in the police version]. My father had to be carried on top of a door,” says Raquel.

Since then, she has suffered from panic attacks and says she wraps herself up in bedsheets whenever there are operations. “I struggle a lot to be able to get out of here. It’s horrible. Any little noise already scares me, I lower myself.”

Jacarezinho is a community in the north of Rio, and in comparison to other favelas like Rocinha or Vidigal, rarely receives tourists.

Alley in the Jacarezinho Favela, in the north of Rio de Janeiro - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

In Jacarezinho, controlled by Comando Vermelho, the reporter was called by a group of armed boys as soon as he entered, close to a train line from which part of the railway sleepers was pulled out and stuck in the next street, to prevent the advance of cars from the police. Passersby carry pistols and rifles on the streets.

The seizure of arms from trafficking is one of the justifications for police operations in these communities. However, with the Covid-19 pandemic, they were limited by the Supreme Federal Court, which now requires justification from the police and communication to the Public Ministry as a precondition for incursions.

In a statement to the STF, the government of Rio criticized the measure, which it said created “a protection zone for criminal organizations of drug traffickers and militiamen, which will result, in a few months, in the record increase in crime.”

Security guard Airã de Oliveira, 29, who has lived in Jacarezinho since he was born, does not deny that the crime is violent. “Unfortunately, we grew up with that,” he says. He jokes when he passes a butcher shop with live chickens at the door. “I don’t even like to see animals being killed. For those who have already seen what I saw, it’s funny, right. When I was a child, I even saw a football game with people’s heads.”

Oliveira says he lost 21 friends with whom he grew up, killed by traffickers or the police. He also lost his father, who was involved in the crime and was killed by accomplices. “It was a life I didn’t want for myself.”

Airã de Oliveira, Jacarezinho resident, whose father was killed by the crime - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

With the police, however, the relationship is different. Two years ago, a cousin was shot in the neck at home, fired on by a policeman who mistook him for a drug dealer, and became paraplegic. “I can’t explain why they are so angry at us. We residents have nothing to do with this war, it’s not our fault.”

“We leave the favela and are already framed, we have to open our arms, open our legs for them to search. That feeling of fear, of making a wrong move, of getting shot,” he says. “A 1 meter and 90 black man …”

Blacks are 75% of homicide victims in the country, according to the 2020 Atlas of Violence, despite representing 56% of the population. They face a 2.7 times greater risk of being killed than non-black people.

With 750,000 people incarcerated, according to data from last year from the National Penitentiary Department, Brazil has the third-largest incarcerated population in the world in absolute numbers, behind only the USA (2.1 million) and China (1.7 million). There are more than 350 prisoners for every 100,000 in Brazil, a total that has grown rapidly in the last century.

The most accepted explanation for the phenomenon is the current Drug Law, 2006, which paradoxically tried to reduce users’ incarceration by imposing alternative penalties. But the text does not define an objective amount of drugs to classify someone as a drug dealer, leaving room for users to be convicted of trafficking.

An appeal by the São Paulo Public Defender’s Office calls for the criminalization of possession of drugs for personal use to be considered unconstitutional. It began to be examined in 2015 and was released for trial by Minister Alexandre de Moraes in 2018, but until today, it has not been placed on the Supreme Court’s agenda.

Drug trafficking is the second-highest reason for imprisonment, corresponding to one in five prisons. Among women, this rate reaches 51%. Most are young people (45% are up to 29 years old) and black (67% of the prison population). Today, 30% of the country’s prisoners have yet to stand trial.

“The available data show that the prisoners are not the traffickers who tyrannically impose themselves on communities through the use of force, but retailers in the trade of illicit substances, who have been arrested without a weapon, without violence and with no known bond with a faction,” says anthropologist and writer Luiz Eduardo Soares.

In his reasoning, this happens because the Military Police are pressured to produce results –which can be shown through imprisonment. As the MP cannot carry out investigations, the Civil Police’s responsibility is to make arrests in the act, many of them for drug trafficking. “We have a selective filter of color, class, and territory, which is that of the prison in the act,” he says.

Police officers at the entrance to Favela da Rocinha, in the south of Rio de Janeiro - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

Inside the jail, the prisoner will need to ally himself with a criminal faction to survive and will owe allegiance to him when he leaves prison. “We are paving a career in crime, hiring future violence.”

Rio de Janeiro today has four main criminal groups. The largest and best known of these is the Comando Vermelho. Still, there is also the Terceiro Comando Puro and the Amigos dos Amigos and the militias, who also do drug trafficking.

The gangs are called prison factions precisely because they appear or are strengthened within the prison system, as is the case of São Paulo’s First Command of the Capital. The factions have cells across the country and associations abroad for international drug production and disposal.

Piquet Carneiro, from USP, says he agrees that prisons strengthen criminal factions. For him, incarceration has a vital deterrent effect, as it provokes fear of being arrested among people who are thinking of getting into crime and takes bandits off the street.

The Complexo do Alemão, where Almeida lives, became a symbol of success and, subsequently, the policy’s failure to combat drug trafficking in Rio de Janeiro. Ten years ago, after a week of attacks on the city, state and national forces occupied the favela, arrested traffickers, and planted a national flag at the top of the hill.

“I looked to one side, and I saw the traffic. On TV, the police coming. And you in the middle of it,” says Almeida, who has seen a series of police raids. The first thing he remembers was in 1992 when the military occupied the favela to guarantee the security of the authorities who attended the Eco-92 conference. At the time, they even demanded work papers from residents who wanted to get through the siege.

“It is not effective. If it were, it would be over [the crime]. It has never changed, and that is not how it will change,” he says. “We need to stop drug trafficking. You look over here, where is there a marijuana plantation here? How does a gun arrive? They criminalize this place. They say that everyone here is either a thug or a thug friend or a thug relative. But nobody is conspiring with anyone. "

Maicon de Almeida, resident of Complexo do Alemão - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

The difference in treatment was evident when Almeida studied in Botafogo, in the south of Rio. Colleagues smoked marijuana near police without any modesty and were not approached.

Chief Zaccone, when working in Jacarepaguá, on the west side of the city, recorded four arrests in the act for drug trafficking on ach shift. The territory of his police station included slums like Cidade de Deus.

“I was transferred to Barra da Tijuca, a prime area, and spent up to six months without making any arrests. You looked at the police reports and thought there was no drug traffic in Barra. Of course, that was not true,” he says.

“What you have are criminalizing policies and differentiated security actions,” says the policeman. If police repression aims to reduce drug use and circulation and protect public health, politics in the country has failed, says the delegate.

“The space of the poor and the poor are considered all the time as dangerous. What legitimizes this violent control of the favelas of Rio and Brazil’s peripheries is the prohibition on drugs. From this aspect, I could say that prohibition has positive results. for maintaining this uneven order in our country. "

Brendo Oliveira, 16, at his home in Complexo do Alemão - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

Brendo Oliveira, 16, black and resident of Complexo do Alemão, knows what this is all about. “Life here is very difficult because of the shooting. We are there, relaxed, children playing, there is a shooting, a resident is hit, and you don’t even know where it comes from,” he says.

Oliveira lost his father and an uncle, drug dealers, who died in exchange for gunfire, but he is sure he doesn’t want that for himself. “It’s death or jail. I am totally different from my father. My life is different: judo, jiu-jitsu, football, art, photography.”

The young man lives near the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) of Fazendinha, a building with bullet holes in the glass and iron plates to contain the projectiles. The facility is at the top of a hill, next to a disabled cable car station.

When created in 2012, the UPP was in a vibrant area, bustling with tourists who used the cable car and filled the bars and the local craft fair. There was a family health clinic and social projects at the station, such as judo classes for children in which Brendo started to practice the fight.

Above, view of Complexo do Alemão, in the north of Rio de Janeiro; below, Laureana Sousa, Mineira, with her husband, Galileu, and their children at Complexo do Alemão - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress

The closing of the cable car in 2016 reduced movement and activities gradually ended until the police occupied the station closed it to the public. The unit became anything but pacifying, says Laureana Sousa, 34, better known as Mineira.

Owner of a bar behind the UPP, she points out the tense relationship of the police with the residents of the region: “Without the police here, the residents know the rules of the hill, what can and what cannot be done, each does their part and there is no violence. You live a peaceful life because a criminal does not knock on the resident’s door. Now, the police come in, invade, mess, humiliate women, and their families.”

“Our governors, today, want to cancel CPFs [kill], no matter who. For them, our children, within the community, are already seeds of evil. The child is growing up to become a bandit, so anything they kill inside the favela is good,” she says.

The repression of drug trafficking ends up concentrated at the end of the deal, says police chief Zaccone, in retail, where the profit is lower, and not in the illicit drug production. “The effect of this is that this market remains economically strong, and we have an immense number of poor black youths jailed and killed in police actions.”

In the city of Rio de Janeiro, the police last year killed 726 people, 38% of the 1,913 inhabitants who died violently in the capital of Rio de Janeiro.

The state government of Rio de Janeiro did not give an interview for this report but sent a note stating that 81% of the state’s 1,413 favelas suffer from groups linked to drug trafficking, and 19% suffer from the action of militiamen.

The government estimates that there would be about 40 criminals in each of these slums, with an estimated 56,620 free criminals carrying large-caliber firearms and serving in drug trafficking or militia groups across the state.

“It is within this reality that the operations carried out by the Civil and Military police are carried out, whose main objective is to locate criminals and seize weapons and drugs,” reads the note. “These actions are guided by information from the intelligence area and follow strict execution protocols, always with the concern to preserve lives.” The state says the number of homicides in the last month of August was the lowest since 1991, as well as the consolidated of 2019.

The government’s figures show that between June –after the STF’s ban on violent operations in communities without prior justification– and August (the latest available data), 798 people were murdered in the state, compared to 1,001 in the same period last year. A 20% reduction helped to reverse the upward trend in police lethality in the middle of a pandemic.

View of the city of Rio de Janeiro from the viewpoint Dona Marta - Eduardo Anizelli/Folhapress